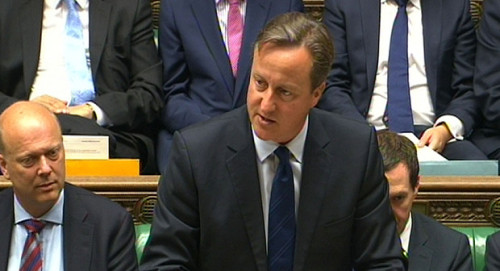

PHOTO: British Prime Minister David Cameron speaks in Parliament on Wednesday (PA)

Responding to criticism after Monday’s speech by Prime Minister David Cameron to Parliament, the British Government says it is preparing a new strategy for Syria’s conflict.

Statements on Wednesday by Cameron and Foreign Secretary Philip Hammond outlined plans for both limited military strikes against the “controlling brains” of the Islamic State and a diplomatic effort for a political resolution — with President Assad retaining power during the six-month period of a “transitional governing authority”.

On Monday, Cameron — responding to the surge in refugees in Europe, many of them from Syria — stole headlines with the announcement of Britain’s first drone strike inside Syria. The attack killed three Islamic State fighters, two of them British.

The Prime Minister said military action would be necessary to prevent terrorist attacks on British soil, pointing to more strikes on the Islamic State; however, he said little about the approach to the Assad regime. As analyst Thomas Pierret assessed:

[This] is a problem of strategy — the strategy is flawed. It is one-sided, addressing only one part of the problem, which is the Islamic State, and not the Assad regime.

See Syria Audio Analysis: Assessing Britain’s 1st Drone Strike — “The Problem of A Flawed Strategy”

Syria Analysis: British PM Cameron’s Drone Strike “Revelation” is a Diversion…and a Cover-Up

Syria Audio Analysis: Political Stalemate and Military Challenges — What Happens Now?

On Wednesday, the Government responded in two linked but somewhat contradictory statements. Answering Prime Minister’s Questions in Parliament, Cameron repeated the promise of action against the Islamic State with “hard military force”. At the same time, he indicated that the Assad regime must be removed:

We have to be part of the international alliance that says we need an approach in Syria which will mean we have a government that can look after its people. Assad has to go, ISIL [the Islamic State] has to go. Some of that will require not just spending money, not just aid, not just diplomacy but it will on occasion require hard military force.

Hammond also promised a revived military and political approach, but his position on Assad saw him as a short-term partner in the process, rather than an illegitimate ruler to be toppled:

We are not saying on Day One [that] Assad and all his cronies have to go. If there was a process that was agreed, including with the Russians and the Iranians, which took a period of months and there was a transition out during that period of months we could certainly discuss that.

British officials later told journalists that Britain would seek the political negotiations “with the blessing of Russia and China”. To get the support of Assad’s key allies, Russia and Iran, Britain and “other Western powers” would agree to the transitional period of up to six months in which Assad will remain in office; however, his security services would be shut down.

London’s approach appears to pick up from the ruins of a Russian-Iranian initiative, begun in late June, for high-level political discussions. The effort collapsed in mid-August when the Saudi Arabian Foreign Minister — at a press conference after a meeting with his Russian counterpart in Moscow — said Assad must leave office before negotiations developed.

Earlier this month, UN envoy Staffan de Mistura presented a plan in which Assad would become a “ceremonial” President, rather than one with executive powers, in a transitional governing authority. Up to 120 regime officials would be barred from further service. However, the proposal was received coolly by both Moscow and Tehran.

A British Solution?

Cameron’s “Assad has to go” was a bone thrown to those who insist the President must be removed. But Hammond’s statement — and the British plan — offered no indication of why the Syrian opposition and rebels would accept even a six-month grace period for a man whom many consider a war criminal, let alone a legitimate head of state.

Nor did either of the men put together the two distinct parts of their statements. How would a show of British military force against the Islamic State contribute in any way to a political solution, given that no military pressure from London — or presumably the US, who appear to be the silent partner in Britain’s plan — will be applied on Assad?

Conversely, how will the President’s continued rule, even if short-term, assisted the effort to curb the Islamic State — given that the widespread killings and abuses by the regime opened the door to the entry of the militants into Syria?

In 2012, British officials said that they were working on an integrated political and military approach to remove Assad. They even indicated — though would not confirm — that there were covert operations, including British special forces, inside the country.

But in spring 2013, those officials commented that they were received little direction from the Prime Minister and his Cabinet. One said, “We are being asked to do something, but given no plan for what we are doing.”

On the surface, Cameron and Hammond are promising a belated redress of the issue. But a fundamental question, which we posed after the Prime Minister’s speech on Monday, remains: “How long will the killing be allowed to continue with no prospect of a ‘safe haven’ for Syria’s civilians?”