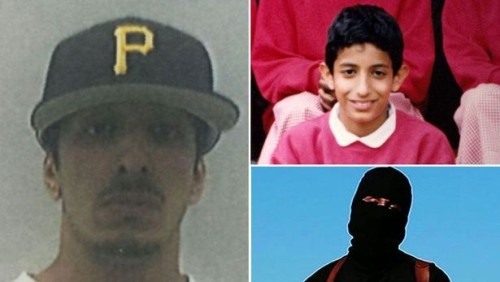

PHOTO: 3 Faces of Mohammad Emwazy (clockwise from left): Age 18, age 7, and as “Jihadi John”

Published in partnership with The Conversation:

On Friday, the Pentagon said that US warplanes had carried out an operation in northern Syria targeting the Islamic State fighter Mohammed Emwazi. In London, the Prime Minister’s office said there is a “high degree of certainty” that the Briton was killed.

If confirmed, Emwazi’s death is the end of the 15-month story of the man dubbed “Jihadi John” by the British media after his appearances in ISIS videos of the beheadings of at least seven hostages.

As most of the developments in Syria’s 56-month became too complex for journalists — let alone the general reader — to follow, this is the story of how Mohammad Emwazi offered the useful alternative of the Islamic State’s evil threatening the “West” as well as those in Syria and Iraq.

Jihadi John Appears

In August 2014, the Islamic State released the video of its first beheading of a foreign hostage, the American journalist James Foley. Beside the kneeling victim stood his executioner, a man shrouded in black, holding a large sword. In British-accented English, he addressed US officials:

As a government, you have been at the forefront of the aggression towards the Islamic State. You have plotted against us and have gone far out of your way to find reasons to interfere in our affairs. Today, your military air force is attacking us daily in Iraq, your strikes have caused casualties among Muslims.

Sequels soon followed with American-Israeli journalist Steven Sotloff and British aid workers David Haines and Alan Henning. Emwazi’s script was disrupted when Abdul-Rahman Kassig, a former US marine who worked with hospitals in Syria, refused to confess on camera — instead, “Jihadi John” had to just pose with the severed head of the victim — but it was renewed in January with the executions of Japanese hostages Haruna Yukawa and Kenji Goto.

Weeks later, Washington Post reporters identified “Jihadi John” as Emwazi. Born in Kuwait but growing up in West London, he had graduated from the University of Westminster with a degree in computer programming. In 2013, he travelled to Syria and later joined the Islamic State.

The Man Behind the Videos

But what had led Emwazi not only to join the ISIS but to carry out gruesome acts for the “group whose barbarity he [came] to symbolize”?

The Post searched for an answer: “Friends believe that Emwazi started to radicalize after a planned safari in Tanzania following his graduation from the University of Westminster.” Some speculated that the process began in 2009 when a post-graduation safari trip to Tanzania went awry, amid monitoring by British security services of a group of West London youth for possible ties with jihadists.

The British campaign group CAGE, to whom Emwazi had spoken, provided details. Emwazi and two friends were detained by Tanzanian police upon arrival in the country and deported. On their way back to the UK, he and one of the friends were interrogated in Amsterdam by an officer from the British intelligence service MI5. The officer accused them of trying to reach Somalia to join the militant group al-Shabab.

Then Emwazi testified that the officer said, “Listen Mohammed: You’ve got the whole world in front of you; you’re 21 years old; you just finished Uni – why don’t you work for us?” When he refused the approach, the officer warned, “You’re going to have a lot of trouble….You’re going to be known….You’re going to be followed….Life will be harder for you.”

In Britain, he and his family were further questioned by security officials. In September, he decided to go to Kuwait, where he worked for a computer programming company. However, in July 2010, British security services prevented him from returning to the Gulf country after a visit to his family in London.

For more than two years, Emwazi was repeatedly blocked in his attempts to travel to Kuwait. In August 2013, soon after a final attempt, he disappeared from his home. His family believed he had gone to Turkey, but were told by security services in December that he was inside Syria.

Choosing the “Right” Story

Perhaps unsurprisingly, CAGE was labelled as an “apologist for terror” for its publicity of the story before Emwazi’s journey to Syria and the Islamic State, including a statement at a press conference that he was a “beautiful young man”. Last month, after an audit criticized the conference, the organization apologized for the presentation — but not the details of the testimony.

It is unlikely that any of that story will make headlines today as the world waits for confirmation that Jihadi John is dead. British Prime Minister David Cameron, declaring the airstrike an “act of self defence”, has set the narrative:

Emwazi is a barbaric murderer….He was Isil’s lead executioner. He posed an ongoing and serious threat to innocent civilians not only in Syria but around the world and in the UK too.

Emwazi’s death would be “a strike at the heart of…this evil terrorist death cult”, Cameron assured.

French journalist Didier François, who was held hostage for 10 months, offered detail of Emwazi’s treatment of detainees: “He was most probably one of the worst, who hit and tortured without the slightest restraint.” The journalist said that Emwazi “took care of selection and then training of jihadists candidates” to send them back to their countries to carry out attacks.

While some newspapers such as The Guardian and The Telegraph referred to Emwazi’s story before 2013, it disappeared in most outlets, as in this video from The Washington Post — now he is simply “the face of the Islamic State”:

When Mohammad Emwazi disappeared from Britain in 2013, so did his existence up to that point. His new identity, from the first beheading video in August 2014, would be tied to the image of the Islamic State and of Western fears of its citizens who had joined the organization, Now he was “Jihadi John”, one of the four British members of ISIS known as “The Beatles”.

Uncertain of how to proceed in Iraq and Syria, the US and British Governments needed an easier campaign to fight. So Jihadi John took his place as one of the Most Wanted of barbarity, his capture or death a goal that would represent “victory” against ISIS — even if his fate would make little difference to the organization.

While Cameron tried to hold up that victory, there was another contrasting voice on Friday that noted the cost of illusion. Dianne Foley, the mother of Jihadi John’s first victim, told US media: “This huge effort to go after this deranged man filled with hate when they can’t make half that effort to save the hostages while these young Americans were still alive.”

![]()