PHOTO: Victims of the multiple chemical attacks near Damascus on August 21, 2013

Two years ago on this day, President Assad’s military attacked at least seven sites near Damascus, in the areas of East Ghouta and West Ghouta, with rockets containing sarin nerve agent.

We will never know exactly how many people died on that day or afterwards from the effects of the chemicals — estimates range up to 2,000. We do know — from videos and from the testimony of medics, victims, and first responders — that hundreds died almost immediately. Believing that the Syrian military was carrying out a conventional attack, many people huddled in basement shelters. Because of the cold weather, the sarin gas sank, turning the basements into death traps.

Within 24 hours of the attack, Russia — unsettled by the threat to its ally Bashar al-Assad — would try out the propaganda line that the attacks were with “homemade weapons”, implying that the Syrian military was not responsible. That line would be developed in the following weeks by the Russians, working with Iranian and Syrian agencies; by pro-Assad activists; and by conspiracy theorists. To this day, some continue the diversion that rebels must have carried out the attacks — again, on seven different sites with rockets held only by the Syrian military — on their own areas near Damascus.

Equally important, the Russians found a diplomatic strategy in late August with the idea of focusing on an Assad handover of chemical weapons stocks. When President Obama suddenly retreated from the possibility of military intervention, the US joined the effort. Eventually, the Assad regime agreed to hand over its chemical stocks. However, chlorine — not covered under chemical weapons conventions — has been used repeatedly by the Syrian air force in the following two years.

The propaganda and political maneuvers may have saved Assad, at least in the medium-term. As we noted, “The unprecedented operation on Wednesday was not a sign of President Assad’s strength. It was testament to his desperation.”

On the day after the chemical attacks, EA’s Joanna Paraszczuk wrote this analysis. We repost it today, both as testimony to the accuracy of the reporting and as recognition of those who were killed.

On Wednesday, the Assad regime surprised and shocked the world with a wave of attacks — probably with chemical weapons — that killed at least 1,360 people in Damascus suburbs.

Within hours, regime warplanes and artillery bombarded the towns hit by the first wave of attacks as well as other insurgent-controlled Damascus neighborhoods, in what appeared to be the opening of a major offensive to reclaim these strategic parts of the capital.

What exactly happened and why? What will the Assad regime, the insurgency and the international community do now?

Was Wednesday’s unprecedented attack a sign that the Assad regime is winning? Or is it a sign of desperation, as the regime fears it is losing, throughout the country and even on the edges of the capital?

The scene at one of the attacked sites:

1. THE WAVE OF ATTACKS

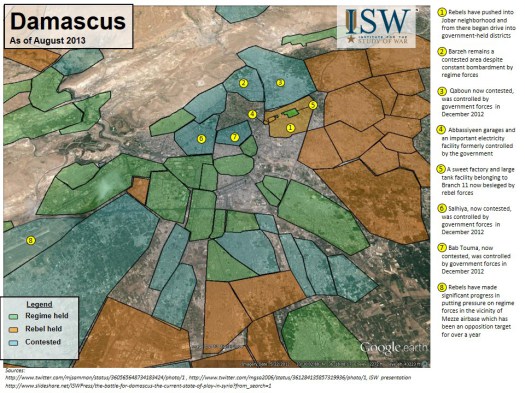

At around 3:30 a.m. Damascus time on Wednesday, August 21, 2013, the Assad regime launched a wave of attacks against towns in East Ghouta and West Ghouta. The attacks hit Jobar, Zamalka, ‘Ain Tirma, Hazzah, and al-Moadimiyeh, with activists reporting that hundreds of people died within an hour.

The victims were taken to local medical points, which quickly became overwhelmed.

As medical staff and volunteers tried to treat the victims, the regime continued to bombard the area with mortars, rockets and heavy artillery. Doctors working at the field hospitals reported that medical staff had been killed in the attacks.

One doctor who treated victims at a field hospital in Jobar reported that the victims showed the following symptoms:

- Breathing difficulties (dyspnea) and suffocation

- General convulsions

- Nausea and vomiting

- Meiosis (constriction of the pupil)

- Increased salivary secretion

The doctor said that, because the field hospital had limited resources, victims were given episodic care only. Treatment included atropine, high concentration direct oxygen, antispasmodics, bronchodilators, painkillers and anti-emetics.

The doctor described the gas as being heavy and sinking to the ground, such that those who tried to shelter from the attack by going into basements presented with more severe symptoms, or had died because they had been exposed a higher dose of the gas.

Doctors and activists also reported that medical supplies were severely stretched, in great part because of a siege imposed by the regime on the area, including on humanitarian aid channels, which has had severe consequences.

Shortly after the first wave of attacks, regime forces began a second wave, striking Muaddamiyyat As-Sham, an insurgent stronghold in the Damascus countryside, near Darayya.

Activists report that more civilians were killed and injured in that second wave of attacks. That wave has continued into Thursday, with airstrikes and shelling in the towns hit on Wednesday.

The first wave of “poison gas” attacks appeared, therefore, to be an initial attack as part of a larger, concerted offensive to take back key areas of the Damascus suburbs.

Victims being treated

2. WHY DID ASSAD DO THIS?

Over the past months, the Assad regime has been under increasing pressure in Damascus, as it has failed to take back key suburbs and neighborhoods with a high insurgent presence.

In March, the regime launched an offensive in the Damascus countryside, with the aim of taking back those areas. The regime succeeded in cutting off insurgents in East Ghouta from supply lines, and in July regime forces managed to overrun parts of the Al Qaboun neighborhood. By late July, however, insurgents succeeded in pushing into the Jobar neighborhood, from where they began launching attacks on regime positions in Damascus.

In the days leading up to the August 21 attack, insurgents launched a series of attacks on regime positions in Abbasyeen, Damascus.

On Monday and Tuesday, footage showed insurgents from the Islamist Liwa Fustat al-Muslimeen targeting the regime’s Civil Defense Office in Abbasyeen — including with Croatian M79-Osa anti-tank weapons.

On Tuesday, State media reported that the attacks caused eight civilian deaths in the Damascus neighborhoods of Abbasyeen and Al Zablatani, with a shell hitting the Al Abbasyeen Stadium.

The regime is not just under increased pressure in Damascus. Elsewhere in Syria, it has faced insurgent gains in key areas — including an insurgent offensive in Assad’s home province of Latakia, insurgent victories in Daraa in the south and in Deir Ez Zor, where insurgents have taken, and so far held, key neighborhoods in the city. In response, the regime has launched counter-offensives, characterized by airstrikes and artillery shelling. However these counter-offensives, together with ongoing in fighting in Homs — where the regime has invested considerable firepower to try to regain control — have spread Assad’s forces thin.

In the days leading up to the attack, insurgents based in Jobar — one of the Damascus suburbs hit in in Wednesday’s attacks and in the ongoing Damascus offensive — launched an assault, including with Croatian anti-tank missiles, at regime positions in Damascus.

Increasingly under pressure, and facing increased attacks on its positions in Damascus and elsewhere, the Assad regime decided to gamble on a major offensive to regain control of the Damascus suburbs. It gambled that the international community would not respond with intervention, and that the attacks would buy him enough time and weaken the Damascus suburbs to such a degree that Syrian forces could carry out a ferocious and swift offensive across multiple targets.

Wednesday’s attack can also be seen as an escalation of another tactic that Assad has employed against insurgent-held areas — that of “terror bombing“, i.e. the use of a ferocious, highly destructive attacks against civilian populations to create terror and fear, in the hope that this will weaken insurgent strongholds.

A victim awakes: “I am alive! Help me, sir!”

3. WHAT WILL THE “INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY” DO NOW?

The “international community” — in the sense of countries nominally supporting the Syrian opposition, such as the US, UK, and France — reacted cautiously to Wednesday’s attacks. President Obama did not make an appearance; instead, a White House spokesman expressed “concern” and called for an investigation of the incidents, a line paralleling that of British Foreign Secretary William Hague.

UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon expressed “shock”, but the UN Security Council was limited on Wednesday night to a general call for a UN inspection team — coincidentally in Damascus, hoping to inspect sites of three earlier alleged chemical weapons attacks — to be allowed to the locations hit on Wednesday. Russia and China ensured that no stronger action was taken, blocking a draft resolution looking for “compliance” from the Assad regime with the requested access for the inspectors.

Indeed, it was Moscow that showed the greatest vigor on Wednesday in supporting the Assad regime’s line on the attacks. The Russians, like others, may have been surprised by the ferocity of the regime attacks, but they quickly put State propaganda into motion to back Damascus, echoing the statements of Syrian State media.

Initially, Moscow’s line was that Western and Arab media were creating the incident to divert from the visit of the UN inspectors. Later, a Foreign Ministry spokesman amplified the Assad regime’s claim of “terrorists” killing civilians, saying that a home-made rocket had been launched from an insurgent-controlled area, and comparing the incident to a previous claimed chemical attack on Khan al-Assal. (The Russians did not explain how a single, home-made rocket with an “unknown chemical” could account for an almost-simultaneous assault on several towns.)

Yet the attention to “international community” may miss a bigger point — that other countries might not show the reticence of Washington, London, or the UN in escalating support for the insurgency. Turkey immediately put out a damning statement, and backed that up on Thursday by slamming the UN, saying that the Security Council failed to act even though “all red lines” had been crossed in Syria. The Saudis preceded the “West” in calling for an immediate investigation.

Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and groups from Kuwait are already providing significant weaponry for insurgents — arms that have contributed to a series of opposition victories across Syria since June and which possibly stemmed the regime’s attempt to take all of Homs. That support, with Turkish acquiescence, is likely to be ramped up in the near-future.

Victims on the floor of a field hospital:

4. WHAT MIGHT HAPPEN NEXT?

The Assad gamble is that the Syrian military can move quickly to pacify the Damascus suburbs once and for all, providing a sense of “security” and boosting morale. The regime’s hope is that this will turn back the insurgents elsewhere, with airpower ensuring the regime holds onto parts of Aleppo and almost all major cities, and bolster the Syrian military as it pounds the remaining insurgent-held areas of Homs.

The key word is “quickly”. Past regime operations near Damascus have brought claims of success, only for insurgents to push back into positions from where they can carry out attacks on the capital. Earlier this month, there was a telling example when President Assad did a photo-op in Darayya, congratulating troops. The opposition pointed out that, as soon the President left, the insurgency were again operating in the town, while activists said that Assad had, in fact, only visited the very outskirts of the insurgent stronghold.

If “quickly” does not occur, then the regime faces a double problem. First, Wednesday’s attacks will not only have produced resolve from some foreign actors to back the insurgents towards victory — they also may encourage the insurgency, despite divisions and disputes earlier this year, towards co-operation in a drive against the regime.

That increase in co-operation was already evident in operations such as the capture of Menagh Airbase in Aleppo Province, in the assault on Deir Ez Zor city, and in successes in the south. Now it could produce more victories in Aleppo Province and a push to claim most of Syria’s largest city.

Then there is the second effect. We have often said that this is not just a conflict of arms but also for “hearts and minds”.

Wednesday’s attack — if it is not followed by quick, decisive victory for Syrian forces — will have eroded the regime’s chances of winning those “hearts and minds”. Despite the regime propaganda, most Syrians will have seen their President and his inner circle kill more than 1,300 of their fellow citizens: that “shock and awe” may be good for a military operation, but as an effective war crime, it does little for long-term support.

Put bluntly, the unprecedented operation on Wednesday was not a sign of President Assad’s strength. It was testament to his desperation. And if that desperate attempt does not succeed….

What else is there that Assad and his advisors can do beyond a chemical attack?