Russian leader Vladimir Putin (R) with Belarusian counterpart Alexander Lukashenko (File)

Originally published by Cosmopolitan Globalist:

UPDATE, JAN 6:

The international humanitarian organization Médecins Sans Frontières has been forced to terminate its assistance to refugees and migrants trapped on the Belarus-Poland border in freezing conditions.

MSF sent an emergency response team to the border in October, after thousands of men, women, and children were lured to Belarus and then pushed to the border with the false prospect of entry into the European Union. At least 21 people have died.

See also Belarus Deporting Syrians Back to Danger in Assad Territory

While the numbers trying to cross into the EU have fallen, groups of refugees and migrants are still reporting ill treatment. On December 18, MSF teams joined a Polish civil society organisation Salam Lab to help five Syrians and one Palestinian who managed to make it outside of the restricted zone. They said they had been forcibly returned to Belarus several times, enduring violence by Polish border guards.

Frauke Ossig, MSF’s emergency coordinator for Poland and Lithuania, said:

Since October, MSF has repeatedly requested access to the restricted area and the border guard posts in Poland, but without success.

We know that there are still people crossing the border and hiding in the forest, in need of support, but while we are committed to assisting people on the move wherever they may be, we have not been able to reach them in Poland.

Ossig added, “Some of the [humanitarian] volunteers have been vilified and intimidated, and had their property destroyed in what is believed to be an attempt to stop them from providing support.”

The current situation is unacceptable and inhumane. People have the right to seek safety and asylum and should not be illegitimately pushed back to Belarus. This is putting lives at risk.

ORIGINAL ARTICLE, NOV 24: On May 23, using the phony claim of a bomb threat, Belarusian fighter jets forced a Ryanair passenger jet en route to Vilnius from Athens to land in Minsk. This was a pretext to arrest one single passenger — the Belarusian dissident Roman Protasevich.

This hijacking and seizure of a political prisoner was the start of the path to thousands of refugees and migrants being trapped on the Belarus border with Poland — and to a possible Russian assault on Ukraine.

Responding to the air piracy, the European Union levied sanctions against high-ranking Belarusian apparatchiks. Belarus’s authoritarian leader Alexander Lukashenko vowed to flood the EU with migrants and drugs: “We were stopping [them]. Now you will catch them and eat them yourself.”

He kept his promise. Over the summer, Iraqi and Belarusian travel agencies sold visas, in tourist packages to Minsk, to migrants seeking to enter the EU. As soon as they arrived in Minsk, Belarusian officials picked them up at the airport and escorted them to state-approved hotels, then bussed them in the dead of night to the Lithuanian and Polish borders. Belarusian border guards gave the migrants wire cutters for the fences.

Behind Lukashenko Is Putin

Using migrants and refugees to destabilize Europe is the playbook of Russian leader Vladimir Putin. From 2015, widespread Russian bombing and sieges forced more Syrians to flee, including into the EU. The ensuing crisis gave far-right, pro-Kremlin figures and proxies the narrative they eagerly sought — one replayed six years later as Kremlin-aligned media portray the events on the Belarusian-Polish border as “a humanitarian crisis” revealing Europe’s pitilessness and hypocrisy.

See also EA on TRT World: Russia’s Role in the Belarus-Poland Refugee Crisis

EA on Happs: Putin’s Tactics Over Ukraine and Belarus-Poland

The Kremlin’s proxies feed their domestic and Western audiences videos and photos of the border, edited to emphasize the suffering of women and children in the cold and the inhuman demeanor of Polish border guards. “Questions about why this happened are unnecessary,” wrote opinion columnist Vladimir Boroda on the RT Telegram channel:

For 30 years the European Union has been shouting that the rights of all people are equal, that it does not matter where a person lives and where he comes from, and that EU countries are open to everyone who wants to settle in Bern, Berlin, Lyon or Marseille. Well, except for the Russians, because they are evil and unpredictable….

Those 3,500 refugees who are now sitting at the Polish checkpoint may want and know how to work. Perhaps they are just really kind and polite people who left the death zone for the sake of hope for the future. Which, by the way, the European Union even promises them. But it does not [allow them in], coming up with completely ridiculous reasons for refusing them—from Belarusian aggression to the Russian conspiracy. Although the reason is simple, it cannot be voiced under any circumstances—otherwise you will have to admit that not all people are the same for Europe, not all are valuable, not all deserve the benefits of European life. And this is the collapse of the entire value system of the liberal Western society, for the protection of which it is not a sin to put up barbed wire and shoot. So far—over our heads.

The majority of the migrants were, indeed, people who left the death zone in the hope of a better future in Europe. They had been led to believe that this was where they were going. Now they find themselves in warehouses in Bruzgi, sleeping in cargo storage units.

See also A Syrian Refugee Trapped in Belarus: “Please, Just Help Me to Live”

Some in the Western media, seeing what is undeniably a humanitarian crisis, have chastised the EU: “The images from the Belarus-Poland border, however harrowing, shouldn’t be surprising,” wrote Charlotte McDonald-Gibson in The New York Times. “This is what the European Union’s migration policy looks like.” She allowed that the greatest share of blame for the crisis lay with Lukashenko, but faulted the EU for fearing “the political effects of large-scale migration.”

This, she argued, had “given authoritarian states a road map to blackmail”:

[European officials] use the language of moral superiority and humanitarianism without the policies to back it up, weakening their authority to call out countries such as Belarus and Russia. They should start redressing those double standards immediately.

She is not wholly wrong. Europe has repeatedly capitulated to blackmail in its dealings with autocratic states who have used the threat of opening the migrant valve to wring concessions from Europe. In a trivial sense, it is true that if Europe opened its borders to everyone, it could not be blackmailed. Europe would do well to provide more legal pathways, as she suggests, for work visas and refugee resettlement.

But Europe cannot provide a legal pathway to every migrant who wishes to settle in Europe. Lost in McDonald-Gibson’s narrative is a focus on Belarus’s geopolitical calculations — and, because Belarus doesn’t act independently, Russia’s. The President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, noted as much when she said, “This is not a migration crisis. This is an attempt of an authoritarian regime to try to destabilize its democratic neighbors.”

The Kremlin’s Foreign Policy: Crisis on the Borders

The border crisis can only be understood in the larger context of the Kremlin’s foreign policy objectives. Lukashenko, an isolated dictator, could not have carried out an operation of this magnitude on his own.

The Kremlin has poured billions of dollars worth of aid — financial, military, intelligence, logistical —into Belarus. Putin is Lukashenko’s senior partner in the Russia-Belarus Union State, which came into being last September when an agreement formally integrated the two countries’ economies and tax systems, as well as their defense and intelligence apparatuses. The Military Doctrine of the Union State subordinates the Belarusian military to Russia’s, codifying Belarus’s role as a Greater Russia satellite state.

The orchestration of the migration crisis required resources Belarus does not have. The money, logistics, know-how, and connections to the underworld of human trafficking and organized crime could only have come from one place — Belarus is infamous for smuggling, but not on this scale.

For Putin, Belarus is a critical launchpad for destabilization and military operations in Poland, Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia. The geography of the border crisis, at the opening of the Suwałki Corridor, is no accident. Endless hours of NATO war planning have been devoted to this narrow finger of land between Belarus and Kaliningrad, one of the most significant and vulnerable territories in NATO. Cut this off, and you cut off the land bridge between the Baltic littoral and the European plains.

Kaliningrad, until 1946 known as Königsberg, is in turn cut off from Russia and surrounded by EU and NATO territory. It is an obvious flashpoint, not least because Baltiysk, just to the west of the city of Kaliningrad, is Russia’s only warm-water port on the Baltic Sea.

For the past decade, Russia has been bolstering its military presence in Kaliningrad, pouring in troops and arms, including Iskander-M Ballistic missile launchers. Their range is depicted in this map from the Polish Defense Ministry:

As tensions over the migrant crisis grew, Russia sent nuclear-capable strategic bombers to practice bombing runs east of the Polish border, then paratroopers to the border for surprise joint Russo-Belarusian drills — an unambiguous signal to the West.

Pavel Latushko, widely viewed as the de facto leader of the Belarusian opposition in exile, has alleged that operatives of Russia’s military intelligence agency GRU are training combat veterans at a base near the village of Opsa in northwest Belarus. Latushko says Belarus intends to send these operatives into the EU to “realize terrorist acts”.

Lukashenko may have hatched up the migrant scheme for domestic consumption, casting himself as a man with a tender heart for blameless immigrants and softening his well-earned image for criminal brutality. But owing to Belarus’s geography, this plot clearly served Putin’s wider objectives.

Putin’s Greater Russia

The Soviet Union was dissolved on December 26, 1991. The 30th anniversary of may well be on Putin’s mind, given his attention to significant anniversaries: for example, the journalist Anna Politkovskaya was assassinated on Putin’s birthday. Then there is his fear: if Ukraine was integrated into a successful and prosperous European sphere, Russians in St. Petersburg and Moscow might want the same thing.

Last summer, Putin published an essay in which he averred that Ukraine and Russia were one people and one nation. The creation of an independent Ukraine, he wrote, was a mistake. On November 18, he said in a foreign policy speech:

It should be borne in mind that Western partners exacerbate the situation by supplying Kyiv with lethal modern weapons, conducting provocative military maneuvers in the Black Sea, and not only in the Black Sea — in other regions close to our borders. As for the Black Sea, this generally goes beyond certain limits: strategic bombers fly at a distance of 20 kilometers from our state border, and they, as you know, carry very serious weapons.

Yes, we constantly express our concerns about this, we talk about “red lines,” but, of course, we understand that our partners are very peculiar and so—how to put it mildly—treat all our warnings and talk about “red lines” casually. We remember well how NATO’s eastward expansion took place—there is a very representative and professional audience here. Despite the fact that relations between Russia and our Western partners, including the United States, were uniquely good, the level of relations was almost allied, our concerns and warnings about NATO’s eastward expansion were completely ignored.

Of late, Putin has been expanding on this theme in his oratory and writing: “The West doesn’t respect Russia. Russian policy must be less diplomatic and more confrontational; the only language the West understands is force.”

No one doubts that Russia’s fear of invasion has a historic basis. But in the modern world, where no one is dreaming of that invasion of Russia, Putin’s perspective amounts to paranoia. He will only feel secure if he controls the periphery and territory near Russia’s borders against the “enemies” of the European Union, NATO, and the “West”. Russian domestic propaganda repeats this theme endlessly.

In 2007, beginning with a massive cyberattack on Estonia, Putin began turning ideas into operations. Fourteen years later, Russia has conducted massive cyber-assaults throughout the West. It has launched proxy wars in Georgia and Transnistria, and tried to stage a coup in Montenegro. It has established networks for disseminating disinformation throughout the world. It has launched hacking, doxing, and sabotage campaigns. It has assassinated dissidents and used chemical weapons on EU soil. It has purchased sympathetic politicians in Germany, Austria, Italy, Serbia, and France.

Russia manipulates the supply of gas to Moldova, Ukraine, and Germany. It has attacked Ukraine and annexed its territory, then isolated it through the construction of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, which circumvents Ukraine as a gas transit route.

In one prominent school of Kremlinology, Putin has no ideology. He’s an opportunist who takes advantage of the West’s weakness, using these tactics to wring concessions from the US and the EU while always skirting away from a full, kinetic war.

Bur irrespective of “ideology”, Putin’s foreign policy since 2007 — and especially since 2014, when Russia invaded Ukraine — is clearly revisionist.

War Games

Russia is waging economic war against Ukraine by diverting its gas supplies, banning key Ukrainian exports, instructing banks to cut financing to Ukrainian industries, and cancelling infrastructure projects.

Last March and April, Russia complemented this economic warfare with a build-up of forces on Ukraine’s border. Continuing this through September, it moved in equipment for the Zapad 2021 (West 2021) exercises which it staged in Belarus. Ukraine’s Defense Minister Oleksii Reznikov estimates that there are now 100,000 Russian troops on the Ukrainian border.

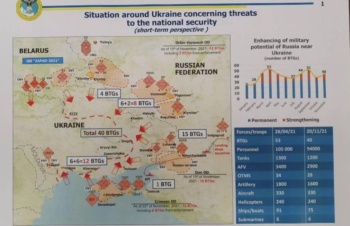

The Ukraine military’s vision of a Russian attack through Battalion Tactical Groups

On November 15, Kyrylo Budanov, chief of Ukraine’s military intelligence, warned that Russian heavy artillery might be positioned to put psychological pressure on Ukraine, but it could also signal an imminent attack. The military preparations have been accompanied by a significant increase in psychological operation, he noted, aimed at destabilizing Ukraine’s political establishment and weakening Ukrainian will to fight. He pointed to protests, organized by Russia, against Coronavirus vaccines in Ukraine.

The most worrisome movements are those of the 41st Combined Arms Army, which has moved from the center to the west of Russia, massing on Europe’s eastern borders. Commercial satellite photos show a build-up of armored units, tanks, and self-propelled artillery, as well as ground troops near the Russian town of Yelnya — close to the Belarus border and less than 300 km (186 miles) from Ukraine. The images indicate the equipment began arriving in late September.

The 41st CAA could be critical in a conflict. It would fill the gap between the 6th CAA in the north, near St. Petersburg, and the 20th CAA in the east, near Voronezh, as an advance force in an attack on the Suwałki Corridor. The 11th Army Corps in Kaliningrad could also support an attack on Poland and Lithuania.

If Russia strikes in the Black Sea region, the 41st CAA could push forward into Ukraine from the north, cutting off Kyiv from reinforcements and then positioning troops on the west bank of the Dnieper River.

Satellite imagery also shows a rise in Russian military personnel, vehicles, and equipment in Crimea and in Rostov, east of Ukraine. This might signal an imminent incursion into the Donbas, where shelling by Russian-led, Ukrainian separatist forces has increased.

Images also show that Russia has sent the National Guards, a paramilitary security force and hybrid operations unit, to Rostov. The Guards are a hybrid-ops unit. The Guards have been used in Crimea and other regions of Ukraine to control occupied territory, suppress dissent, and install Kremlin puppets.

The troop movements and the massing of weapons on Ukraine’s border are quite different from Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, or from the military exercises in March and April 2021. Moscow’s attempt to obscure the movements alarmed EU and US diplomats. On November 4, US President Joe Biden dispatched CIA Director William Burns to Moscow to warn that the US was aware of and alarmed about the build-up.

German, French, UK, Baltic, and US leaders have all reiterated their support for Ukraine’s territorial integrity. But these leaders understand full well that the Kremlin will respond with destabilization campaigns against their governments and societies.

Will Ukraine Be Defended?

Even if Putin is merely an opportunist, an attack on Ukraine may be opportune. Although Germany and France have publicly stated they will not tolerate Russian aggression against Ukraine, neither may act decisively for Kyiv.

Germany has not yet formed a government following its recent elections, and it is dependent on Russian gas. German establishment figures, such as Wolfgang Schauble, have limply proposed asking the Kremlin for help in solving the migrant crisis which it orchestrated in Belarus. In France, the ambiguous views of French President Emmanuel Macron on Russia are accompanied by an election year. Europe and the United States alike are mired in the pandemic and its economic fallout. Both are battling a vociferous anti-vaccination movement, spurred by Russian disinformation.

If Russia attacks Ukraine, what would the US do? Americans would be asked to do the heavy lifting, with EU and NATO partners scrambling. President Biden is focused on Coronavirus, climate change, and China. The US domestic political environment is toxic, with Americans more and more divided; self-absorbed, and indifferent to the severity of fires blazing abroad.

Would NATO come to Ukraine’s aid? If the West’s response to Russian kinetic and non-kinetic warfare since February 2007 is any guide, the answer is No. Endless initiative for diplomatic dialogue and expressions of deep concern have allowed the world’s autocrats to operate with impunity.

In the long term, deterrence requires strengthening the armed forces of EU member states and increasing the resilience of their societies. This has started, but more needs to be done — and quickly.

In the short term, both Ukraine and Belarus’s neighbors need support. If Russia attacks Ukraine from Belarus or Crimea, the EU and the US must be prepared to levy crippling sanctions on Russian authorities. They must prepare to send more military personnel and materiel to Ukraine.

For now, the British have sent 600 troops, and the US has reinforced the Ukrainian Armed Forces with radar and medical equipment, ammunition, and precision weapons. On November 10, Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba signed a strategic partnership charter to deepen the two countries’ political, security, defense, economic, and energy ties. The US has sent warships to patrol the Black Sea, and initiated high-level defense meetings with NATO member Turkey. Turkey in turn has announced it will sell more Bayraktar TB2 drones to Ukraine one of which destroyed a Russian howitzer in October. NATO has also increased the tempo of meetings and briefings among its defense ministers.

The US House of Representatives has passed an amendment to impose mandatory sanctions on Nord Stream 2 AG, the company that runs the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, through an amendment to the National Defense Authorization Act. (Biden had issued a waiver on sanctions, allowing Nord Stream 2 AG to complete the pipeline.) The amendment is now in the hands of the US Senate, which will vote on it soon.

Ukrainians have been at war with Russia since 2007. If Russia invades, they will fight back. But leaders and analysts in Europe and the US are divided. Some think Putin is just bluffing. Some seek to de-escalate tensions. Some are calling for more visible solidarity and an immediate show of force.

Ukraine and Ukrainians don’t have time for this debate. They need the EU, NATO, and the US to act decisively.

Now.