Bharat Malkani of the University of Birmingham writes for The Conversation:

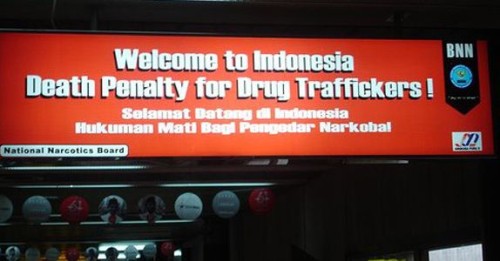

Indonesia has endured a great deal of criticism for continuing to execute men and women at an alarming rate. Things have come to a head thanks to the case of the Bali Nine, a group of people convicted of drug smuggling that includes various foreign nationals.

Interventions from Australia, Brazil and France, all of whom have citizens lined up for execution, have fallen on unsympathetic ears. On February 25, Indonesia’s president, Joko Widodo responded to international criticism by saying foreign nations should not interfere with Indonesia’s right to use capital punishment, and that the executions were therefore justified in going ahead as planned.

But in terms of international law, Widodo is wrong on various counts.

Yes, Mr President, Intervention is Justified

Widodo’s claim that “there shouldn’t be any intervention towards the death penalty because it is our sovereign right to exercise our law” would not have been correct 50 years ago, and is certainly not acceptable today.

The way a country uses capital punishment is of global concern. When international human rights law was laid down in the wake of World War II, the world initially disagreed on whether the death penalty is a matter for the international legal system – but in 1966, it was ultimately agreed that death penalty laws and practices should be regulated by international law.

Indonesia’s recent wave of executions has involved numerous foreign nationals. The right of states to exercise diplomatic protection over citizens abroad goes back centuries, so there is nothing untoward about the likes of Australia, Brazil and France making representations to help their nationals facing execution. In fact, in a feat of sheer hypocrisy, Indonesia is helping its own nationals escape death sentences abroad.

Indonesia is imposing the death penalty for drug-trafficking offences. Even if we accept that states are permitted to use the death penalty, there is an unequivocal ban on the death penalty for non-fatal offences. The UN has made it abundantly clear that only those who directly cause a person’s death are eligible for the death penalty, and has explicitly prohibited the death penalty for drug trafficking. To suggest that other countries should not speak out when a state is flagrantly breaching international law makes a mockery of the international legal system.

Indonesian President Joko Widodo (Dennis M. Sabangan/EPA)

Widodo has also said he will not consider clemency for drug offenders – yet international law makes it clear that each case for clemency must be considered on its individual merits. Yet again, when other countries are threatening to violate rules of international law, states are bound to intervene.

There are a host of other concerns with Indonesia’s use of the death penalty against drug offenders. Widodo has said that the punishment is required in order to deter others from bringing drugs into the country, but there is simply no evidence to suggest that the death penalty has deterred people from trafficking drugs before. The evidence also suggests that the drug crisis in Indonesia is not as severe as state authorities have made out when attempting to justify their use of capital punishment.

In other words, the death penalty is neither necessary or effective. Not only is it morally questionable to impose death sentences in such circumstances, it is also legally dubious.

The “Small Mercy” of Firing Squads

Only one element of this situation is short of a worst-case scenario. Indonesia is arguably meeting one standard of international law: the requirement that executions are carried out humanely and with respect for the dignity of the offender. This standard is by no means met in all the countries that still execute criminals.

In several states in the US, for example, the use of lethal injection has come under increasing scrutiny as evidence comes to light that people executed that way still feel pain, and that the method can go disastrously wrong. Even many states and countries that still embrace execution have rejected hanging, the electric chair, and the gas chamber because it was recognised that these methods of execution cause excessive suffering – yet many other governments still deploy these and other means.

By contrast, Indonesia’s use of firing squads is more humane. Research has suggested firing squads, while by no means perfect, are the most reliable means of executing a person quickly and with minimal suffering.

But it says a lot about the death penalty that arguably the most effective and humane way of carrying it out involves pointing a gun at someone and shooting them. The boundary between officially sanctioned state killing and illegitimate homicide is easily blurred to say the least – and it seems that the only remotely laudable aspect of Indonesia’s institutionalized death penalty is also one of the most disturbing.