Following reports that a Russian private security firm hired a number of Russian contractors to carry out security missions in Syria, Russian-language newspaper Sobesednik has published an interview with a Russian private security contractor who says he was hired to guard “objectives” in Syria.

The Sobesednik story sheds new light onto the reasons why the Russian private security personnel were sent to Syria, and the recruitment process by the private security firm, Slavonic Corps Ltd.

According to Slavonic Corps Ltd, whose founders have experience in providing private security services overseas, mostly related to guarding ships against pirates in the Indian Ocean, the initiative was created on January 18, 2013 in Hong Kong, to guard oilfields and oil pipelines between Kirkuk and Banias in Syria.

Slavonic Corps says it obtained a license from the Syrian Security Committee (No. 8/559) for the execution of armed security services, and also signed a contract with the Syrian Ministry of Electrical Energy (No. 001/S).

According to one man who was working for the private security firm, and who was approached for recruitment to Syria, the contract was linked to a close associate of the Assad regime who wanted to hire private security personnel to guard energy facilities in Syria.

Slavonic Corps tried to recruit 2,000 personnel, that source said, but failed and recruited less than 300.

Those who were recruited were deployed to Syria but were ambushed by a large deployment of insurgents en route from Latakia to as-Sukhna. The head of Slavonic Corps Ltd says that the Russian group asked for assistance from the Syrian Government (specifically from the Ministry of Defense) but none was given. The group managed to escape with only seven casualties — albeit two serious cases — and were evacuated on two Syrian charter flights back home to Moscow.

Upon arrival, the Russian FSB arrested several of the group’s leaders. Nothing is known about what came of those arrests.

See our previous coverage of this incident:

Syria Special: The Tragi-Comedy of the Failed Mission of Russia’s Military Contractors For Assad

Russia Spotlight: Amended Legislation Targets Russians Fighting In Syria

We have translated the full article below.

SOLDIERS OF MISFORTUNE

Sergei says that he fought for someone else his whole life, and now he’s fighting for himself. It turned out that having special forces experience, knowledge of how to handle a weapon and familiarity with tactical fighting after the crazy Nineties, is once more in vogue.

“I left the special forces a few years ago now, because I got fed up with living on a low salary, most of which had to go on living costs, while only those who were close to the bosses had a chance to get an apartment! At that time, I started to see ads recruiting trained people with military experience and knowledge of foreign languages (I speak English and Arabic). I called, I had two interviews. After that I started to work, escorting naval vessel in the Indian Ocean, and guarding against Somali and Nigerian pirates.

“Russian security is valued there, because (Russians) are far cheaper than the British, while their training and moral capacity isn’t any less,” Sergei says of his service history in the private security firm “Slavonic Corps”.

“In March, I suddenly got a phone call and was asked whether I wanted to take part in a ground operation,” Sergei continued. “They described it rather vaguely: “the Middle East, guarding objectives, the rest you’ll find out later!”. The salary was $5,000 – $8,000 per month, not including expenses. I was assigned to a medical orderly in the reconnaissance platoon.

“I was already on my guard: securing industrial objectives, and assignment into groups, just like a special operation: snipers, grenade-throwers, intel. I enquired through my networks — where were we going? It became clear that the company was gathering a brigade of 2,000 people to go to Syria. And they had a terrible shortfall, they put the call out even to those in military service in the special forces, they asked people to quit and go (to Syria). A day later, they called — they asked about clothing measurements, footwear, and even asked to meet to sign paperwork and give them my passport for a visa.

“I understood that this was a full military operation, and for sure came under the penal code as “Mercenaries” (Article 359 of the Penal Code – Editor). As I read news about street fighting, as I watched videos from Syria, I understood that there’s a total mess there!”

Sergei refused to go to the “foreign war”. But a brigade of 300 people, mostly those released from the army, did sign up to go to the hotspot. Those who came back are saying that the fight was small but definitely not victorious.

A WAR WITHOUT ANY PARTICULAR REASON

“What happened in Syria I know only from talking to my friends who went there,” Sergei says, “As they told me, they were hired by the “Syrian Abramovich”, a local “energy baron” who is friendly with Assad. Only when they got there did it become clear that rather than guard objectives, they were required to fight back against militants. There was absolutely zero security, there weren’t enough places to sleep, and people had to sleep on the floor. They were given old, broken weapons. There was very little ammunition. And fighting against us were around 800 militants, and not just simple militants either — Talibanis, Pakistanis, Afghanis, black turbans, the most seasoned fighters! In short, our guys wound up under an ambush for a couple days. And the militants kept on coming!

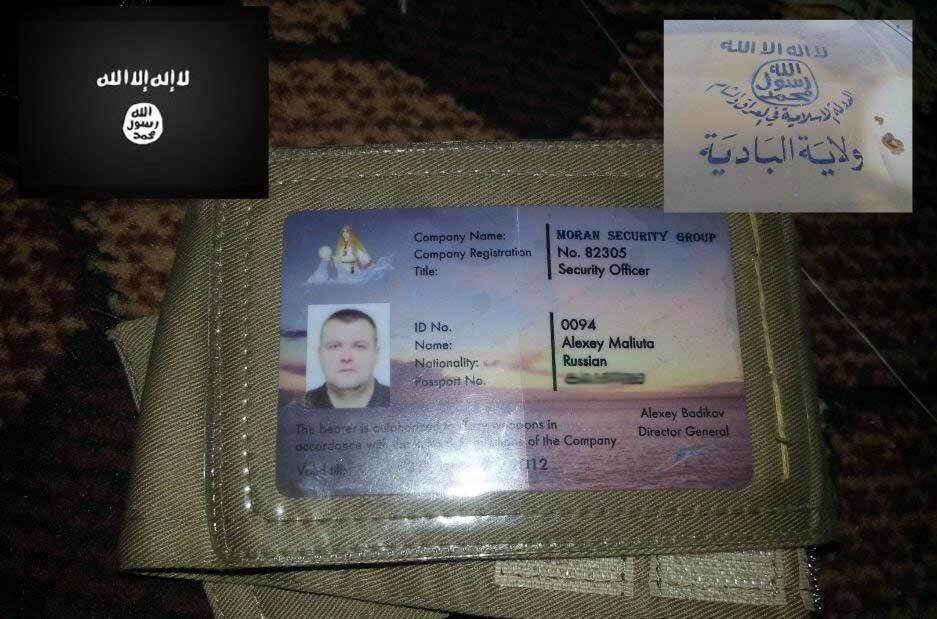

“The first fight turned into a scandal — the militants captured photo and video material that proved there was a “Russian presence”. Initially, the owner of the bag — a guy from southern Russia named Aleksei Maliuta — was identified as having been killed. Only after the confusion subsided did it become apparent that none of the Russians died in the confrontation with the militants, though five of our guys were wounded, two seriously, and the commanders of the group decided to leave all their things behind and get out.”

The military adventure failed miserably — at the airport in Russia, the “Russian mercenaries” were met by FSB agents. Two leaders of the company were arrested as were several of the group’s commanders. As those who took part in the inglorious operation, several of them were sent money in boxes after the got home — to the tune of $4,000, others just got IOUs. Maliuta, who was “buried” by the media, went on record once, saying that he returned home and celebrated his rebirth.

Since then, he has not responded to phone calls and letters about the “Syrian brigade”.

A PRIVATE ARMY

In Russia there are several private security firms. There is no legislation relating to their activities. They are a small, but fully combat-ready army. In the West, this phenomenon has long existed — in Afghanistan and Iraq alone there are hundreds of private security firms operating. The mercenaries are referred to as “wild geese”, the most remorseless(*) thugs taking part in military coups and overthrowing governments.

“The private military firms have a very wide spectrum of operation — from sensitive army tasks, which the regular army cannot undertake for political reasons; military consulting, guarding, preparing military equipment, to domestic tasks, like local support for troops and logistical aid,” Oleg Krinitsyn, the head of RBS-Group, one of Russia’s largest private security firms, told Sobesednik. “Right now, the main speciality of Russian private security firms is naval: defending ships from pirates in the Indian Ocean.”

The are rumors going round the private security firms that Slavonic Corps, the company behind the scandal in Syria, had help from the highest levels, and that engaging in questionable transactions had led to business problems — in Nigeria, one vessel belonging to the company was detained and the firm took serious losses trying to “close” via an expensive gamble.

This is not the first time that military personnel, who are armed and ready to make money, have raised questions about the legality of private security firms. In 2011, Vladimir Putin was asked that question, and he promised to consider it.

During these times, one of the social networks published an ad about the recruitment of volunteers for Syria. Judging by the comments, the “adrenaline-filled vacancy” aroused a lot of interest. Ten thousand dollars for a five-month trip and what was practically a “suicide contract”, $1,750 in advance, the rest at 20% of the contract each month. Insurance in case of injury or death, $20,000. Leaving for battle: $1,000. If you are lucky enough to stay alive, of course.

WE’VE COME UNDER FRIENDLY FIRE!

The director of Slavonic Corps, Sergei Kramskoi, gave a response to Sobesednik.

“The project was created on January 18, 2013 in Hong Kong to guard oilfields and oil pipelines between Kirkuk and Banias in Syria. For the work, we obtained a license from the Syrian security committee (No. 8/559) for the execution of armed security services, and we signed a contract with the Syrian Ministry of Electrical Energy (No. 001/S).

The deployment to Syria took place from September 9, 2013 through October 3, 2013, there were 268 personnel. On October 17, 2013, the company’s personnel were taken from Latakia to the region of Sukhna, where it underwent a massive ambush from militants, numbering around 2,000 men from 25-30 brigades, with heavy weaponry and two T-62 tanks. Russian speech was heard among the attackers (presumably from mercenaries from a “Chechen battalion, who are fighting on the side of the Syrian opposition). The company’s personnel were dragged into the battle. We asked for help from the Syrian Ministry of Defense, but we didn’t get any. It was practically a miracle that we managed to get our personnel out without heavy losses (we had five light casualties and two seriously wounded casualties). After that we decided to abandon the project and evacuate all the personnel. Two charter planes were hired for that purpose from Syrian Airlines.”

Translator’s note: the piece uses the word “отмороженные”, which literally means “frost-bitten”, but which comes from a slang term meaning “to use violence unnecessarily”.

(Featured image: an identity card belonging to Aleksei Maliuta, a Russian hired by Slavonic Corps Ltd, whose bag was captured by insurgents near as-Sukhna in October 2013)