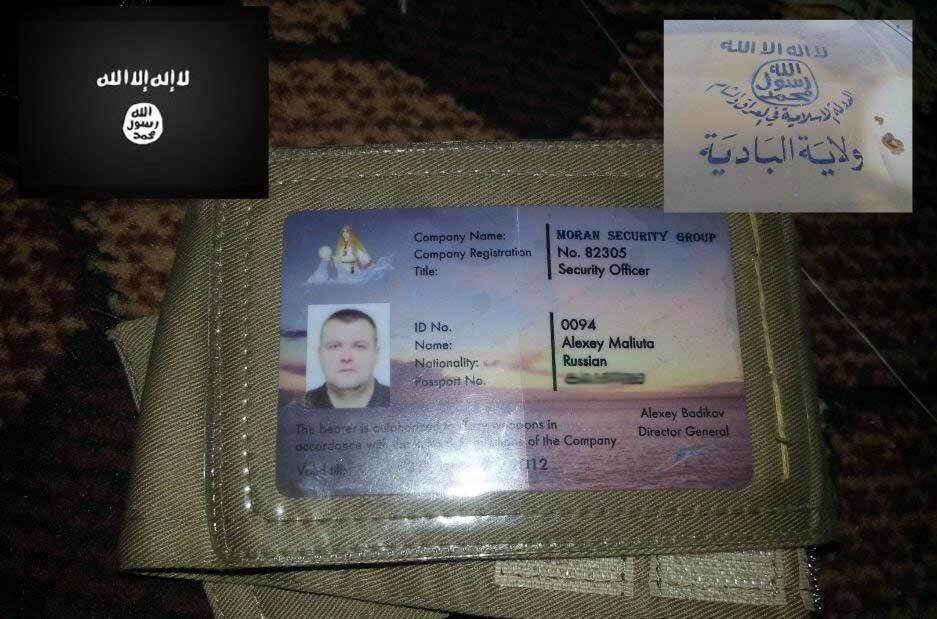

PHOTO: The ID card of Alexei Malyuta — did the Russian contractor die in a botched mission in Syria?

See also Russia Spotlight: Amended Legislation Targets Russians Fighting In Syria

The lengthy sequel to our story on November 1 asking, Are Russian Private Military Contractors Guarding Regime Economic Objectives In Syria?….

After a series of black-comedy mishaps from the start to finish of a failed, short-lived mission, two high-ranking employees of security firm Moran Security Group have been arrested by the FSB (Federal Security Service) on suspicion of sending 300 Russian security experts to Syria.

The developments suggest a bungled attempt by a private Russian company, without the assent of the Government, to profit from the Syrian conflict and Moscow’s support of President Assad.

Last month, the Moran Security Group denied allegations that one of its employees, named as Alexei Malyuta, had been killed by insurgents in Syria. EA translated parts of a longer investigation by the Russian newspaper Fontanka into the claims, which revealed apparent links between the Moran Security Group and another organization, Slavonic Corps, allegedly involved in recruiting Russian security experts to fight in Syria.

Fontanka managed to contact Malyuta’s brother, who said that Alexei was alive and well and had returned to Russia. Malyuta’s brother said that a small group of Russians had been privately contracted to guard Syrian economic interests.

Now Fontanka has a follow-up story detailing the black comedy of the contractors’ mission. It begins:

Since spring 2013, an advertisement for “Slavic Corps” for the recruitment of former soldiers with combat experience, to work on long trips abroad appeared on specialized sites across Russia. Many responded. Not all retired officers of the Russian Airborne Forces, or Special Forces soldiers, or those discharged from the Special Rapid Response Unit (a spetznaz of the Interior Ministry) and riot police managed to adapt themselves to civilian life. For some people, going to an office five days a week is the norm, while for others, the norm is a sharp knife. And not everyone who knows how to skilfully handle a machine gun or sniper rifle has the talent to be a businessman. It’s boring in the big city, the time to be brave and dashing is over, and being a security guard is humiliating and not very lucrative.

The proposal of $5,000 a month to protect of certain “energy objectives” interested former Petersburg policemen, former officers of the Internal Troops of Russia, currently bodyguards.

So a haphazard adventure began:

People literally signed contracts with the Hong Kong company Slavonic Corps Limited kneeling on the concourse of the Leningrad railway station: “Come on, come on, time is running out!” Of the approximately twenty candidates who turned up, three turned around and went home instead of Syria when they saw the details of the Hong Kong company.

The rest took a chance. They were lured by a promise to get $4,000 every month and a solemn oath that the first tranche would be transferred in the coming days….

Next up was a flight to Beirut, Lebanon and a transfer by car to Damascus. From the Syrian border they traveled with a convoy of local guardsmen. A local hotel, then an airplane to Latakia, and a military base.

What happened next? Fontanka quotes one of those recruited:

The large field between Latakia and Tartous was surrounded by barbed wire. There were Syrian reservists and our battalion. Previously, it was a race track. We were housed in the former stables. By October, there were 267 people from Slavic Corps, split into two companies. One company was staffed by Kuban Cossacks of the Kuban and the other by people from all over Russia, there were about 10-12 guys from St. Petersburg. As the commanders said, the the Syrian corps was expected to reach about 2,000 people.

In addition to assault rifles, the battalion were given machine guns, and grenade launchers. Anti-aircraft guns of a 1939 model. Mortars from 1943. Crews were formed for the four T-72 tanks and a BMP. The question of how the arms corresponded with the task of guarding objectives was obvious even to the most gullible.

The situation in Syria was not what the recruits were expecting, as one recalled:

When they talked to us in Russia, it was explained that we would go under contract with the Syrian government, were were reassured that it was all legal and everything was in order. Like, our government and the FSB were informed and involved in the project. When we arrived at the place, it turned out that we were sent, like gladiators, under a contract with some Syrians who either had something to do with the government, or not … That is, we were a private army for a local authority. But there was no going back. As they said, a return ticket costs money, and we would earn it, like it or not.

Slavic Corps told the recruits that they were to retain control of the center of the oil industry, the city of Deir Ez Zor. But first they had to get there. It was more than 500 kilometers away, through territories controlled by government troops, some by the opposition, and some places where it was not clear at all who was in charge.

The first operation that the recruits had to undertake was a total failure, Fontanka reports: the armored BMP given to the “troops” was from 1979 and a complete wreck. The Syrians replaced a working T-72 tank with a rusty old T-62 that was not battle ready and had to be abandoned. When the recruits finally set off, it was in a convoy of Hyundai buses and Jeeps, decorated with pictures of Bashar al-Assad.

Fontanka describes the hopeless journey:

Maybe they would have gotten through, but on the way the valiant and unpredictable Syrian air force interfered. A helicopter pilot who either didn’t want to look more closely at the caravan, or not to scare it with a simulated attack betwixt the desert and the endless sky managed to find a wire, get tangled in it and fall onto the column. He succeeded in slightly wounding one “legionnaire” and mangling the car of another. The mangled chopper and pilot had to be dragged to a military airfield in Homs, and the tempo was lost.

The recruits spent two days at the military airfield. Then, on September 18th, there was a sudden alarm — insurgents had attacked the neighboring town of Sukhna.

About three or four hours later, the recruits were taken somewhere upthe road, to some burning city under fire. They spread out and began to defend.

The detachment of Cossacks moved to the left and the rest joined in the clash with someone who was not Bashar al-Assad. Mortars were launched, which, however, did not manage to reach the column of insurgents. A government self-propelled gun approached, supported by fire….

The militants, who according to various sources,n numbered 2,000 or 6,000, proved stubborn, apparently they started to surround the battalion on three sides. The Slavic Corps, not wanting to die in vain for the ideals of the Syrian state, jumped into the car and started to retreat . During this retreat, most likely, Alexei Malyuta’s backpack was lost, and captured by some of the regime’s opponents .

Six of the Russian recruits were wounded, but all were removed from the battlefield and safely returned home, Fontanka reports.

The journey back to Homs and then to Latakia was grim, Fontanka continues. There was a huge row between the Russian head of Slavonic Corps, Vadim Gusev, and the Syrian “boss”, mostly about money and a sum of $4 million that the Russians thought they were owed.

Nevertheless, the battalion returned to Latakia. While in September Syrians had practically greeted them with flowers, they now looked at them if not as enemies, then definitely not as heroes. They looked surly. Soon they began to slowly disarm the Corps, who had to surrender their heavy weapons. In the end, they even took the automatic rifles. It’s said that without an automatic rifle, there’s nothing for a Russia to do in Syria.

The trip was supposed to last five months, but by the end of October, the Russian recruits were piled onto charter planes and sent home.

Fontanka relates:

At Vnukovo (airport) they not expecting such a reception…. As each one left the aircraft, each fell into the hands of FSB officers. A quick inspection, removal of their SIM card and any other information storage device, brief questioning as witnesses. Then they were handed their passports, non-disclosures and a ticket home. Vadim Gusev, who was flying in business class and left the plane first left at the disposal of investigators.

As the Moran Security Group explained, he and another employee of the company responsible for staffing, Yevgeny Sidorov, were arrested in a criminal case brought by the metropolitan unit of the FSB in an unprecedented application Article 359 of the Criminal Code, regarding mercenaries.

However, the FSB’s response to a question from Fontanka about Syria and the Slavonic Corps was that “such information is not available.”

Regarding the money due to the Slavonic Corps fighters, Fontanka writes:

The nuance is that almost no one has succeeded in getting the $4,000 that should have been paid to each “security specialist” from Slavonic Corps at the beginning of the second month of the trip, and now there are about 200 very angry men in various parts of Russia who are determined to get their money. But Gusev and Sidorov are in Lefortovo (a Moscow prison), so you can’t ask them. None of the “legionnaires” have ever set eyes on Sergei Kramskoi, whose signature is on the contract. People from St. Petersburg say they met with the leaders of Moran Security Group, Vyacheslav Kalashnikov and Boris Chikin, who recruited them to work in Syria. But they explained that it’s not their business, they have no relationship with Slavonic Corps, and there is not and never will be any money.

Fontanka says it tried to contact Kalashnikov again, but got no answer. Instead, the newspaper asked the head of Russia’s largest private military firm, RSB Group, for comment. Oleg Krinitsyn said:

The widely publicized campaign of recruiting mercenaries to Syria initially sounded like a joke, a kind of PR campaign. Then, people believed it and were drawn to the dream of making money. But not everyone understood that this money is dirty and possibly involved blood. Before you send people to a country where there is active fighting, where there is a “layered cake” of the Syrian army, the opposition fighters, Al- Qaeda, al- Nusra, etc, you have to prepare them, as well as understand how you’re going to get them out of there.

Among those guys who were photographed near Syrian equipment, festooned with weapons, I noticed a few of our former employees who were dismissed from the company for low morale. I saw guys with criminal records. This once again confirms that the recruitment task was not to attract high-quality professionals, but just to plug a “hole” with cannon fodder, and to do that fast. And these lads were sent on contracts resembling suicide bomber contracts. People signed up to a contract with a request to bury their remains in their homeland or, if that proved impossible, in the country where they died and then rebury them in Russia. It’s horrible.

Reactions from Russian-language, pro-jihad sites

The Chechen-based website Kavkaz Center, which takes a pro-jihad stance and which supports the existence of a “Caucasus Emirate” in the North Caucasus region, was the first to publish details of insurgent claims that Russian mercenaries had been fighting in Syria.

In response to Fontanka’s latest publication, the site noted that the Russian intelligence services were likely unaware that private security firms had sent “security experts” to Syria, and that the FSB were trying to cover up the operation to avoid being embarrassed:

Kavkaz Center’s publication of the facts of the participation of Russian mercenaries in the war in Syria, fighting for the Assad regime, has clearly aroused the interests of the Lubyanka. Judging by the secret nature of mercenary activity of Slavonic Corps, and vague attempts by the FSB to downplay the level of involvement of Russians in military action in Syria, the data released by KC was a surprise to Russian intelligence, and has obviously not gone unnoticed by Russia’s Western partners.