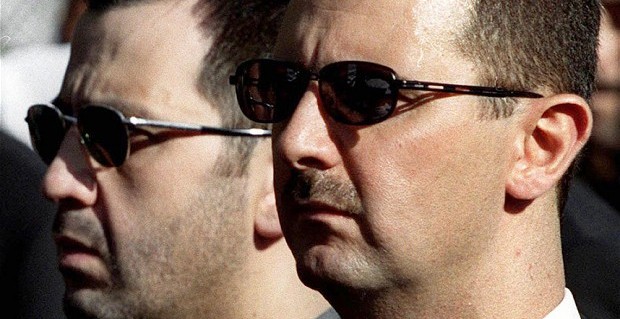

PHOTO: President Assad with his brother Maher, a military commander (Getty)

In a report for the German Institute for International and Security Affairs, Khaled Yacoub Oweis explains, “Without dismantling the sectarian crux of Assad’s rule, Syria peace talks Are unlikely to usher in stability.”

The conclusion of the eight-page study:

A common chant by demonstrators in the early months of the Syrian revolt was “Rami Makhlouf [the businessman who is President Assad’s cousin] and the 40 Thieves”. But the friends of Bashar would not have achieved control over Syria’s economy without partnering with the security apparatus, which has been responsible for the killing, torture, rape, and disappearance of countless Syrians since the revolt — a fact nowadays often forgotten by the international community due to the rise of al-Qaeda-affiliated groups and the Islamic State. Yet, without structural changes to Alawite domination and an end to the disenfranchisement of the country’s Sunni majority and the system of control and corruption, no sustained resolution to the Syrian civil war is likely, even

if a deal is struck in Geneva.

Indeed the framework for next year’s Geneva talks between the regime and the opposition appears to set the stage for a deal that would expand participation in the government and parliament but would not address the structural impediments to an inclusive and less repressive and corrupt system. Some Sunnis could sign on to such a compromise, but it would do little to halt the larger insurgency or rebuild the country and its institutions, and would instead allow the failed old system to continue.

For a solution that could garner significant Sunni backing as well as broader Syrian support, Geneva would need to focus on dismantling the Alawite deep state and the business-security nexus that has financed it. Otherwise, reconstruction could end up involving the same robber barons who rode roughshod over reformists….

But only pressure put on the regime by international sponsors of the talks, particularly Russia, could result in a peaceful dismantling of the plethora of sectarian security outfits, which have had close links with Moscow since the Alawite takeover of power in the 1960s. In this regard, amnesty could encourage Alawites in the security apparatus to leave office, especially those in the higher ranks who have amassed the most loot. A compensation mechanism would also have to be negotiated to deal with land disputes, one that allows Alawites to keep property they may have acquired illegally before the revolt, since a major reason that Alawites stick with the regime is the fear of a restoration of property rights to their former owners. But no reconciliation can be

achieved without an overhaul of the legal system. This would need to include an agreement to identify the most corrupt judges and those closely linked with security and to consign them to retirement.

In the field of post-conflict reconstruction, Iraq is a cautionary tale. Billions of dollars were spent for rebuilding, but corruption deepened and infrastructure barely improved from the catastrophic levels experienced during UN sanctions from 1990 to 2003. Iraq’s new rulers have done little to establish better governance. In addition, jihadists fed off the failure of the government to integrate Sunnis in the political system. Among the lessons of Iraq is the damage dealt to the remaining technical talent in the bureaucracy through a de-Baathification policy that extracted members of the Baath Party across the bureaucracy, regardless of rank and degree of involvement in the Saddam era. Some technical staff eventually attended ideological rehabilitation courses offered by post-Saddam governments and re-joined the bureaucracy. But many soon left because they could not cope with what they regarded as a suffocating atmosphere. Similar to Saddam’s Iraq, many Baathists officially joined Syria’s Baath Party to increase their leverage in government employment. The party itself has been ruling in name only, with the top Alawite tiers taking over real power. The proposed Syria talks should focus on how to redress the imbalances in

the bureaucracy without replacing Alawite sectarianism with Sunni sectarianism.

In addition, it is imperative to curb the existing monopolies. If the fragmentation of Syria is halted and large-scale projects were to become feasible, reconstruction funds would need to be kept away from an untested post-conflict government and placed under international administration,

which could award contracts to Syrian firms only if they meet disclosure and anti-corruption

criteria. But the start of reconstruction is likely to be small-scale in areas where ceasefires prove to hold. Already there exists a possible nucleus to identify and meet local needs in the form of the Syria Recovery Trust Fund. Set up under the auspices of Germany and the United Arab

Emirates in 2013, the fund was established as an international reconstruction mechanism, but it has been financing only small projects in non-regime areas, due to a lack of security and an active opposition government on the ground.