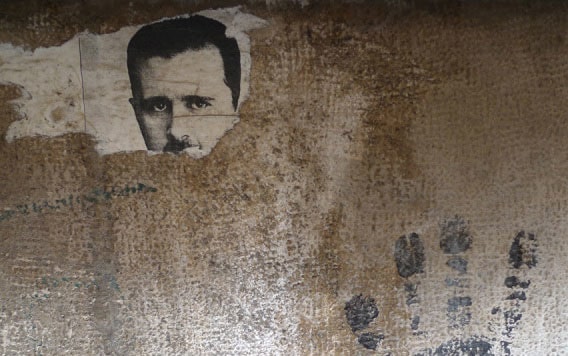

A torn poster of Bashar al-Assad on a wall in central Damascus (File)

Syria’s Assad regime is planning an election show on May 26, rubber-stamping another seven years in power for President Bashar al-Assad and proclaiming his legitimacy.

But Syria’s refugees are not lining up to join the performance.

Al Jazeera English speaks with some of the 1.7 million Syrian refugees in Lebanon about their doubts and fears.

The Assad regime’s State TV have proclaimed that the refugees will vote as an “expression of their resilience against unjust Western schemes and sanctions”, broadcasting shots of a few people registering at the Embassy in Beirut. Interviews were set up so men could declare that the election “compliments” the regime’s army reoccupying much of Syria.

But away from the regime cameras, refugees expressed their disdain for both the ballot and the propaganda.

Abu Ali al-Hamoui, 39, who was a teacher in Hama Province, said, “The elections are just a vaudeville show….They indoctrinate you to support the Baath Party ever since you’re in the first grade.”

He recalled that, after his participation among hundreds of thousands in Hama rallies in 2011, “We got threats. First, they told me, ‘You are an educated and decent man. Be careful. We’re watching you’.”

Hamoui eventually left Syria when he faced forced conscription.

About 5.6 million Syrians are refugees. Another 6 million have been displaced inside the country by the 121-month conflict.

The total of 11.6 million is more than half of Syria’s pre-conflict population of 22 million.

In 2014 the regime staged the first Presidential election since the Assad family took power in 1970. Two nominal opponents — one of which declared his support for Assad during the campaign — were selected. The official return credited Assad with 88.7% of the vote. There was no voting in areas controlled by the opposition or Kurdish groups, as well as exclusion of many refugees and the displaced.

Parliament has announced submissions for candidacy from 22 people on this occasion.

Syrian refugees and expatriates can register through a Google form provided on embassies’ social media channels. The registration requires the information on identity cards, town or city of origin, mobile phone number, parents’ names, and current address of residence.

In a survey of 500 displaced Syrians in late 2020, most supported a vote in principle. But they doubted that it would be free and fair, and more than 80 percent said they would not feel safe walking into an embassy.

Haya Atassi of the Syrian Association for Citizens’ Dignity, which conducted the survey, explained the fear of surveillance and reprisals: “Many Syrians are afraid to go to the embassy – especially in Lebanon. You don’t know if your papers could be confiscated. People are afraid to pass through checkpoints, so how can they go to election centers?”

A Vote in a “Culture of Terror”

Journalist and documentary maker Hoda al-Khatib said she had not registered for a vote that “won’t make a difference”: “If anything, they’ll just put me on their radar and cause more problems for someone from my family there. It’s like signing up to criminalize yourself.”

Khatib, whose documentary about the Syrian uprising was released in late 2020, said, “The regime has created this culture of terror. People don’t talk about politics. Everything is on the down low, and everyone is afraid of each other.”

The Assad regime is waging a PR campaign proclaiming that refugees are eager to return to a safe Syria. Those in Lebanon beg to differ, even though at least 90% of them live in poverty and about 50% are food insecure.

Teacher Hamoui notes, “Back in Hama, the situation is bad: no electricity, no water. We had basic infrastructure even before the revolution and relied heavily on agriculture – but now we’re going back to the primitive.”

Sara Kayyali of Human Rights Watch summarizes:

The Syrian government’s guarantee of safety is meaningless. If you go back, no one can save you. It’s up to you, your luck, and if you have enough money to go back.