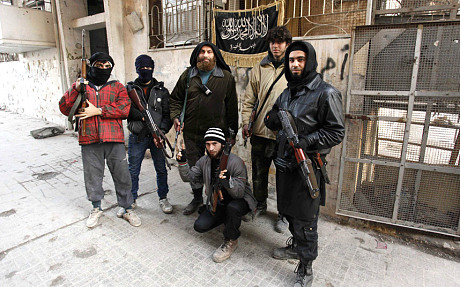

PHOTO: Jabhat al-Nusra fighters in Aleppo Province

Why do Syria’s youths join extremist groups?

International Alert, a peace-building organization, offers answers based on the experiences of 311 young Syrians, their families and community members in Syria, Lebanon and Turkey. The research also includes study of online forums, and monitoring and evaluation from projects in 13 locations.

The study concludes — in contrast to many of the headlines in international media — that political and religious “radicalization” is not the primary cause of young people join factions such as the Islamic State and Jabhat al-Nusra.

Instead, the economic and social situation of each person is the key factor. Unsurprisingly, once you get beyond misleading generalizations, the catalysts are the effects of violence and the lack of education and opportunity.

SUMMARY

Vulnerability among young Syrians is being generated by an absence of a means to serve basic human needs. In many instances, violent extremist groups are effectively meeting these needs.

The most vulnerable groups are adolescent boys and young men between the ages of 12 and 24, children and young adults who are not in education, internally displaced persons (IDPs) and refugees without supportive family structures and networks.

Radicalization is not an explanation for joining a violent extremist group per se. For Syrians, belief in extreme ideologies appears to be – at most – a secondary factor in the decision to join an extremist group. Religion is providing a moral medium for coping and justification for fighting, rather than a basis for rigid and extreme ideologies.

The ongoing conflict creates the conditions upon which all vulnerability and resilience factors act. Addressing these factors without addressing the ongoing conflict is unlikely to succeed in preventing violent extremism in the long term.

The main factors that drive vulnerability are:

1. lack of economic opportunity;

2. disruptive social context and experiences of violence, displacement, trauma and loss;

3. deprivation of personal psychological needs for efficacy, autonomy and purpose; and

4. degradation of education infrastructure and opportunities to learn.

Resilience exists to the extent that the vulnerability factors are addressed in combination (that is, one factor alone will not provide resilience). Alert’s research suggests that the main factors that underpin resilience are:

1. alternative and respected sources of livelihood outside of armed groups, which give individuals a sense of purpose and dignity;

2. access to comprehensive, holistic and quality education in Syria and in neighbouring countries;

3. access to supportive and positive social networks and institutions that can provide psychosocial support, mentors, role models and options for the development of non-violent social identities; and

4. avenues for exercising agency and non-violent activism that provide individuals with a sense of autonomy and control over their lives, as well as a way to make sense of their experiences.

CONCLUSIONS

The findings of this research project suggest that there are many factors that influence an individual’s decision to join an extremist group. Primary data showed that economic, ideological and social motivations may overlap to attract and consolidate support for such groups, both at the level of young fighters and their

communities.

Many Syrians bear grievances connected to the violence and loss of loved ones,and many desire revenge against the Assad regime. Fighting with an armed group provides an instrument through which boys and young men in particular can express grief and physically act upon their anger. Communal social values and religious beliefs are central to young men’s identities, and consequently these can be mobilized by extremist groups to recruit them and consolidate support for the groups. The research also revealed that, for many individuals in Syria, economic imperatives – the need to earn a living – are among the most significant factors influencing their decision to join extremist groups. Finally, the breakdown of educational and other social structures is contributing to vulnerability to varying

location-dependent degrees.

This report has also shown that the resources and conditions that build resilience against recruitment include supportive, stable social networks consisting of family and friends who can guide young men towards positive avenues and provide psycho-social support; satisfying livelihood opportunities that offer adequate compensation and

equitable working conditions; opportunities to engage in non-violent activism; and affordable and accessible educational opportunities for all ages.

Based on these findings, it can be concluded that, for interventions to be effective in preventing recruitment to extremist groups and/or to directly support fighters to leave extremist groups, they must respond to sources of vulnerability in comprehensive ways, recognizing their inter-connectedness. Specifically, interventions must:

• provide alternative sources of livelihood outside of armed groups;

• increase access to education and continued learning;

• reduce the barriers to education for refugees;

• provide alternative non-violent avenues for activism that afford young people a sense of purpose, empowerment and the ability to affect positive change; and

• promote strong, supportive social networks that enable young people to deal with grievances, trauma and the desire for revenge.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The following recommendations aim to guide donors, policy-makers and implementers seeking to reduce the engagement of young Syrians in violence, including violent extremism:

• invest in comprehensive education, accompaniment and livelihood programmes that address the most significant vulnerability factors holistically;

• provide humanitarian and development agencies with technical support to design and implement programmes that address vulnerabilities to violent extremism and measure impact;

• improve targeting of individuals or groups identified as particularly vulnerable, including IDPs [internally displaced persons] in Syria, teenage boys and young men;

• directly engage parents and communities in programming;

• understand and address violent extremism in context (in other words, via a community-based approach that ensures interventions are developed in tandem with and led by local implementing partners who know and have the trust of their communities, rather than using centralized and modular program designs);

• integrate social cohesion objectives into humanitarian aid projects, regional policy objectives and bilateral diplomacy, aiming to reduce discrimination and stigma towards refugees, which can act as a driver towards recruitment; and

• support further research into the effectiveness of preventative interventions including the development of tools for measuring impact and increased resilience.