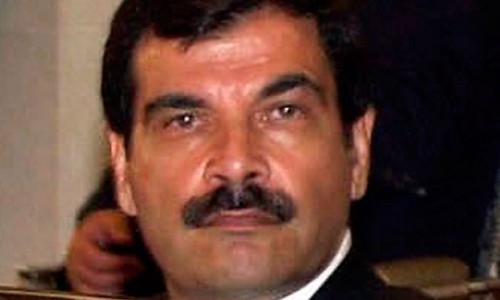

PHOTO: President Assad’s brother-in-law Assef Shawkat, killed with three other high-level officials in July 2012 bombing

On Friday, the Wall Street Journal published a dramatic “exclusive”:

On the fourth day of a rebel assault on President Bashar al-Assad ’s seat of power in Damascus, an explosion tore through offices of the National Security Bureau, killing the president’s brother-in-law and three other senior officials….

New revelations point to a startling theory about the bombing that killed Assef Shawkat, an army general who was Mr. Assad’s brother-in-law and the deputy defense minister: It was an inside job.

The attack also killed Minister of Defense Daoud Abdullah Rajiha, Assistant Vice-President Hassan Turkmani, and the head of the National Security Office, Hisham Ikhtiyar.

Sam Dagher, a highly-regarded reporter on the Syrian crisis, says he has “two dozen” sources for his revelation of the conspiracy behind the bombing. However, if you break down the 2,500 words of the article, this is all of the evidence:

1. Manaf Tlass, a Syrian general who defected two weeks before the bombing, says that “he and Mr. Shawkat were among those calling for talks with both peaceful and armed regime opponents, a position contrary to Mr. Assad and his intelligence and security agency chiefs”.

Dagher continues, “Mr. Tlass and several people with knowledge of the matter said Mr. Shawkat posed a threat to Mr. Assad’s rule.”

2. An opposition activist and a businessman say “Mr. Shawkat seemed to be the regime representative most interested in the discussion” of a negotiated settlement in Homs in December 2011.

3. “A leading Syrian opposition activist” says the insurgency did not have the capability at that time for such a deadly attack: “We were amateurs back then.”

4. Flamboyant Lebanese politician Walid Jumblatt says, “In my opinion, they got rid of [Shawkat]. They were scared of him.”

And that’s it.

The article has no eyewitnesses to the incident, and it has no physical evidence linked to the bombing. Despite the claims of the two dozen sources, it has no figure with a past or present link to the regime other than Tlass and the unnamed businessman.

The article does not explain why the situation had become so critical in July 2012 — after the regime had recaptured much of Homs after a bombardment that levelled part of the city — that Shawkat had to be killed, nor does it explain why only he and not others in the regime who favored a political resolution was targeted. It does not consider why the regime planned an attack which would also kill the Minister of Defense and two other high-level officials.

And Dagher does not indicate why Tlass, who now lives in Paris, stayed silent for almost 2 1/2 years after the events and why the General now chooses to break that silence.

The sum total of this lengthy piece is not “revelations” of “an inside job” — it is speculation which gets us no closer to the bombing that killed Assef Shawkat in July 2012.