Will a President Rouhani make a difference?

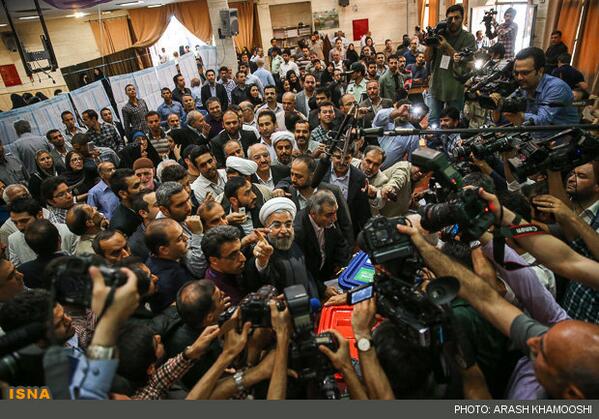

Last Friday’s election of Hassan Rouhani has brought a rush of sweeping claims from neo-conservatives, Washington think-tanks and pro-regime talking heads about how much power Iran’s next President will or will not have.

These range from the neo-conservative mantra that “the Supreme Leader controls everything” to pro-regime platitudes about “multiple, competitive power centers”.

However, Rouhani is not sworn in until the beginning of August. Until then Mahmoud Ahmadinejad — remember him? — nominally heads the Government. And for weeks after Rouhani’s inauguration, his attention will be focussed on putting together his cabinet, rather than on implementing policies.

So, instead of definitive predictions, here are four guidelines to the political context for “what’s next” under a Rouhani Government.

1. THE NEGOTIATION WITH THE SUPREME LEADER

No Iranian President can get far with any initiative opposed by the Supreme Leader’s office, especially in a key area of foreign policy or “national security”. The turning point in Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s political fortunes may have been in Spring 2011, when he tried and failed to take control of the Ministry of Intelligence from Khamenei’s inner circle.

On the other hand, the President is not politically impotent. He not only can manoeuvre for influence, but can also take a lead on economic matters — as Ahmadinejad did with his flawed subsidy-cuts initiative. The President can also press for change in the foreign policy arena. Iran’s embrace of nuclear talks in 2909-2010 — the closest it has come to an accord with the US and European powers — was in part due to the persistence of Ahmadinejad, even if he was later sidelined.

However, don’t expect Rouhani to make any breakthrough statements on a topic such as Iran’s relationship with Syria — his influence there will be on tone, rather than substance. But it is likely that, amidst the Islamic Republic’s economic difficulties, Rouhani will given latitude to see what he can do with his emphasis on effective “management” and sensible policies.

On the nuclear talks, the signs are that Rouhani will be able to work with the Supreme Leader’s office on a revised approach to the “West”.

And what of Rouhani’s promise to expand “freedoms”, including the relaxation of censorship and the freeing of political prisoners like detained 2009 Presidential candidates Mir Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi? In fact, this might be the defining test of the President’s political ability and room to operate.

2. OTHERS IN THE SYSTEM

The negotiation of Rouhani’s power is not just between the Supreme Leader and the President. Iran’s complex political system offers scope to others to exert influence, albeit to differing degrees.

Those include Parliament, led by Speaker Ali Larijani; the judiciary, headed by Larijani’s brother Sadegh; the Ministry of Intelligence; the military, including the Revolutionary Guards with their extensive economic interests; the Basij militia; the seminaries; conservative and principlist parties — and even reformist and opposition factions, despite the detention and intimidation of their leaders and supporters.

President Ahmadinejad’s power was eclipsed not only because he crossed the Supreme Leader. He was also crippled by a running feud with Parliament, especially over his economic policies, and by tensions with the judiciary. He also picked a fight with the Revolutionary Guards over corruption and smuggling.

Rouhani is unlikely to be as abrasive as Ahmadinejad, and the early signs — including meetings with each of the Larijani brothers — are that he will establish a co-operative relationship. However, there will be elements who will be opposed to his proposals from the outset, and he will face the immediate challenge of getting approval for his Cabinet after his August inauguration.

3. THE “WEST” PLAYS A PART

Western advocates of a deal over Tehran’s nuclear program have asserted that the US and its European partners can make a difference with a positive approach to Iran.

There are political motiviations behind that argument, but it is grounded in reality. The Supreme Leader has not flatly opposed to discussions with the West — after all, there were rounds of nuclear negotations between Iran and the 5+1 Powers in February and April — or with the US.

Instead, what Khamenei set out is that any direct talks with Washington must be grounded on American recognition of Tehran’s sovereignty, including over its nuclear efforts. That signal has been repeated on numerous occasions by Iranian officials over the last four months, including by Rouhani in his first post-election press conference.

Even more important, the influence of a “positive” approach over Rouhani’s future extends to the primary issue of the economy. Sanctions are not the foremost cause of the Islamic Republic’s troubles, but they do play a signficant role.

If Washington maintains — and, as signs before the elections indicated, extends — its sanctions-first strategy, hoping to bend Iran to acceptance of the American demands on the nuclear front, then this will impact and limit Rouhani’s possibilities on the economic front.

That, in turn, is likely to affect the President’s political fortunes and opportunities beyond the economy, including in negotiations with the West over the nuclear issue.

4. SO, WHAT NEXT?

We will not have confirmation until the fall of what President Rouhani’s power will be. However, even before then, we can still watch out for signals about the possibilities.

The Supreme Leader’s office, perhaps to avoid taking the blame over Iran’s economy, was generally content with letting Ahmadinejad pursue his agenda in that sphere. The problem for the President came from other quarters, notably the opposition from Parliament and other conservative/principlist factions.

Rouhani and his team are likely to have space at least to try to set Iran’s economic ship back on course, with Ali Larijani’s declaration of co-operation suggesting a “honeymoon” period with Parliament.

In the longer term, though, the issue may not be Rouhani’s power, but his success or lack of it on the economic front.

While an issue such as Syria will remain in the Supreme Leader’s domain, the signs are that Rouhani will have a prominent place on the nuclear question. He is on good terms with Ali Akbar Velayati, Ayatollah Khamenei’s senior advisor, and former Minister of Interior Ali Akbar Nategh-Nouri is a key liaison between Rouhani and the Supreme Leader’s office.

In contrast, Saeed Jalili — the current lead nuclear negotiator, backed in his Presidential campaign by Khamenei’s son Mojtaba — has been sidelined by his poor performance last week, giving Rouhani the possibility of naming his successor.

Yet while the economic issue is paramount and the nuclear question will get international question, the immediate test for Rouhani may be on his promise of “freedoms”. The reformists who agreed to support his candidacy will be looking for some movement after years of repression, especially since the 2009 election, and the house arrests of Mousavi and Karroubi are likely to be a significant test case.

While some detainees are likely to be quietly released, the prospect of a public step is unclear, to say the least. On Thursday, the Supreme Leader’s office appeared to set down a marker by condemning those in the 2009 “sedition” and saying that “they must be subject to law”.

Can Rouhani, for all his pragmatism, negotiate his way between the Supreme Leader — who sharply rejected an appeal in 2010 by Rouhani’s mentor, former President Hashemi Rafsanjani, over the abuse of political prisoners — and those who may look for change beyond economic recovery?