Cas Mudde recalls that, when he wrote “The Populist Zeitgeist” in 2004, the catchy title and topic were bound to gain traction. The double whammy of Donald Trump’s election and Brexit in 2016 was a further accelerant.

So when COVID-19 struck in 2020, it was reasonable to expect the twin forces of a global pandemic and the “populist zeitgeist” to combine and intensify populist politics. Scholarship of populism had already explored how crises, both real and constructed through discourse, are used to demonize establishment elites and defend the supposed interests of ‘the pure people”.

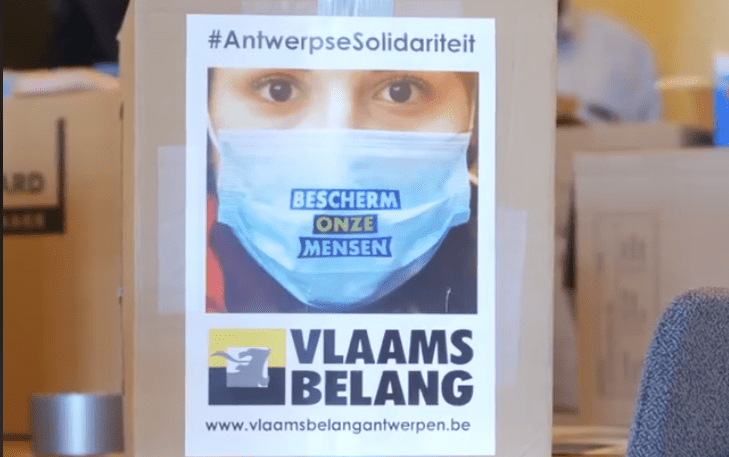

When I first analyzed the response of Belgium’s Vlaams Belang (Flemish Interest) to Coronavirus, I claimed the party was using the crisis to critique the national government and establish its credentials as a member of a future ruling coalition.

See also Coronavirus Shapes Belgium’s Government and Populist Opposition

But eighteen months later, after linking Coronavirus to fundamental policies over Flemish independence and hostility to migration, Vlaams Belang has somewhat bucked expectations. It has not sought to amplify the sense of alarm or to encourage scepticism about experts as a political strategy.

Closing the Window of Opportunity?

In the initial days of the first lockdown, Vlaams Belang used Coronavirus as a window of opportunity to criticize the Belgian Government. Refusing to support the administration, newly formed to pass Coronavirus regulations, the party engaged in regular attacks for several months with an air of “I Told You So”. Party leader Tom van Grieken argued in a June 2020 column in the party’s magazine:

You might wish to forget it, but Belgium was a country in crisis before the Coronacrisis. With the highest taxes and debts, borders that leak like a sieve and politicians who cannot look beyond their own interests. A country in which the population — quite rightly — no longer has any confidence in the traditional parties. The total mismanagement of the Coronacrisis has confirmed that mistrust of the people.

The party levelled a series of critiques against the Belgian Government concerning the supply of masks, the extent of testing undertaken, levels of financial support for small businesses, and travel policies. Vlaams Belang also published a Coronavirus ‘Blunderbook’ in July 2020, which listed the government’s supposed missteps.

This blanket opposition and mobilization against the Government’s Coronavirus response did not last, at least not to the extent apparent in March 2020. Vlaams Belang’s attention to the issue dropped considerably after July 2020. Nor did VB turn towards Coronavirus scepticism as some other populist parties and leaders, like Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil, did. Van Grieken’s single flirtation with a more sceptical position occurred in October 2020, when he refused to download the Government’s track and trace app because he had “no confidence in the Belgian state”. He then performed a swift about-turn, admitting early in November that ultimately his “concerns about privacy were unfounded”.

Like other opposition parties in Belgium and elsewhere, the Vlaams Belang focused its criticism of the Government’s Coronavirus policies squarely on alleged economic impact. The defense of Flemish small businesses became the main point of attack towards the end of 2020 and throughout early 2021.

So Vlaams Belang’s response did not match pre-existing expectations. VB displayed the characteristics of anti-establishment parties more generally, rather than through an explicitly populist response with the rejection of a demonized elite and a promotion of a “pure” people. It focused on negating the Government’s proposed Coronavirus response at each turning point, with populist (either anti-elite or pro-people) rhetoric taking second place.

Closing One Door, Opening Another?

This turn away from the Coronavirus as a focus of the party’s work may be explained by the difference between external crises and those “created” or constructed by populist actors themselves. Perhaps because the Coronavirus crisis is external and cannot be controlled by VB, the party sought to pin it onto narratives closer to its core issues like Flemish independence.

VB’s approach is exemplified by their call in June 2020 for an “exit plan” from Coronavirus and from Belgium. Meanwhile, Van Grieken has focused on becoming a party of government and policy rather than just an opposition with a reputation for rebelliousness in its rhetoric and street politics.

In Belgium, the populist radical right walks a careful tightrope. On the one hand, it is shifting attention from COVID to its longstanding claim of a crisis of representation. On the other, it is emphasizing simple anti-establishment politics rather than populist arguments.

This analysis draws on findings from a chapter, co-written with Dr Steven Van Hauwaert and soon to be published in Populists and the Pandemic (eds. Nils Ringe and Lucio Renno).