Europe’s growing family of radical right parties has a new member in a country previously considered outside the camp.

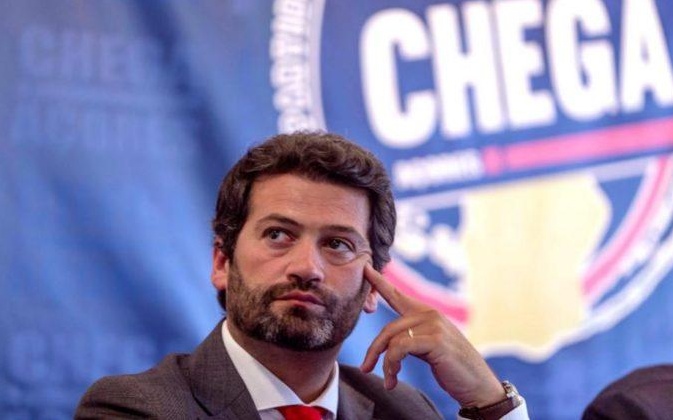

The Portuguese party Chega (Enough) made headlines on January 24, thanks to 12% of the Presidential vote for its leader and sole MP, André Ventura (pictured).

The share was enough for third place in the ballot. Perhaps more importantly, Ventura has taken advantage of the contest for unprecedented personal visibility and for the establishment of Chega as a serious political competitor.

Meet Chega, Meet Ventura

Officially founded in April 2019, Chega took 1.3% of the vote in the October 2019 legislative elections, as one of three parties to gain Parliamentary representation for the first time.

But Chega has benefited far more than the Iniciativa Liberal and the left-wing Livre in its legislative presence. It has profited from the tabloid-like style and rhetoric of Ventura: combining anti-establishment stances with the targeting of out-groups, it is a radical novelty in the Portuguese political scene.

Not only is Ventura the party’s only public face, but the party is held together by allegiance to him. Adherence to the leader is so strong that it is often said that the party fosters a “cult of personality”. Though this is far from sufficient to prevent internal feuds — which have little to do with the leader, and more to do with intraparty power plays and personal antagonisms — there is one undisputable truth accepted within the party: Ventura is the uncontested leader and there is no Chega without him.

Chega was initiated by Ventura to put forward an agenda and give him a political pre-eminence that he had been unable to pursue as a member of the centre-right PSD (Partido Social Democrata). His sense that there is fertile ground for a project like Chega dates back to the 2017 local elections when, running as a PSD candidate in Loures, a municipality on Lisbon’s outskirts, he targeted the Roma community for allegedly living on welfare benefits. His relatively good results, as well as the unprecedented media coverage for local elections, were his first clear signs that the politicization of “politically incorrect” topics could be a successful strategy.

Unable to disseminate his agenda within the PSD, and increasingly frustrated at the party’s internal hierarchy and centrist course, Ventura quit in October 2018 and launched Chega, counting on the assistance of friends, acquaintances and, crucially, social media.

Glenn Kefford and Duncan McDonnell have noted perceptively that, while leaders are usually the expression of parties, “personal parties” turn this formula on its head. This seems to be the case with Chega so far, not only because Ventura created it and is its only face of the party, but because its very existence — at least for the time being — depends entirely on him.

However, on paper at least, Chega aims to be a party with an organizational structure and internal life similar to that of mainstream parties, and in contrast to Geert Wilders’ radical-right Freedom Party in the Netherlands. Chega has established party conferences, regional branches, a youth wing, and a rapidly expanding) membership base with 25,000 as of January 2021.

Growing Pains

There are tensions between establishment of a properly functioning party and the firm control of its leader. While there appear to be internal democratic processes, Ventura has more than enough leverage to steer the party in the directions that he desires.

This was most apparent at the party’s September 2020 convention, where Ventura struggled for approval of his list of candidates for the party’s board. Refusing to give in, Ventura submitted the same list three times, threatening to resign if it was not endorsed at the third attempt. He prevailed.

Ventura’s grip on the party tightened in December, when a directive confirmed sanctions against those who publicly criticize other party members or the leadership in the press or on social media. The leader justified the decision by claiming that he is addressing a climate of internal strife that is damaging the party’s reputation — a climate attributed to the party’s “growing pains” with its rapidly expanding membership, lack of organisational capacity to absorb them, and the alleged infiltration of “opportunists”.

It is too soon to tell how such tensions will unfold. On the one hand, the party is keen to expand its grassroots presence and maximize its electoral appeal. On the other hand, personal parties tend to be “weak, shallow and opportunistic” as organizational entities.

The André Ventura Show

Ventura’s ideal model seems to be a party where power is concentrated at the top, but where the base is occasionally called on to directly elect the leader — a model which is not radically different from other parties in Portugal. This formula endows the leader with a legitimacy which allows him to justify sidestepping middle-ranking party members, as Ventura did at the party’s September convention. In a quintessentially populist fashion, Ventura claimed then that power should remain with the grassroots (i.e., him) and not with “behind-the-scene party structures”.

Chega’s prospective problems have less to do with lack of internal democracy and more to do with internal conflict and an overreliance on Ventura. As the recent implosion of Thierry Baudet’s Forum for Democracy in the Netherlands has shown, infighting, infiltration by extremist, scandals, or simple strategic miscalculations can undermine personal populist parties, And even if leaders are skillful political players.

The long-term viability of the Chega project is critically dependent on the party’s ability to attract the electorate by not relying exclusively on its leader’s appeal. It also must improve its organisational structure, ironically ceasing to be a personal party.

For the time being, there is no figure within Chega that comes close to Ventura in terms of appeal and rhetorical skill. Though this could be a symptom of the party’s youthfulness, it is in clear contrast to another new radical right party, Vox in Spain, which several figures appearing next to leader Santiago Abascal.

For now, Chega remains the André Ventura Show.