“If the President bounces back onto the campaign trail, he will be an invincible hero, who not only survived every dirty trick the Democrats threw at him, but the Chinese virus as well.”

Despite — or, more likely, because — of its casual racism and misinformation, Miranda Devine’s pre-election opinion piece in The New York Post was eagerly quoted by Donald Trump on Twitter.

Trump also revelled in — and amplified — the image of “invincible hero” over his recovery from Coronavirus. Indeed, as he demanded his release from Walter Reed Military Hospital, he told aides that he would make a dramatic exit: as he left through the front doors, he would feign weakness and fragility — only to suddenly stand tall, open his dress shirt and revealing a Superman T-shirt underneath.

This is Trump’s ego. But it is also his long-standing performance of strongman masculinity: from aggressive businessman and casino owner to The Apprentice’s “You’re Fired” host to trash-talking star of World Wrestling Entertainment.

Synonymous with authoritarian statesmanship, it is an image that privileges masculine strength, authority, and security at the expense of equality, inclusivity, and social cohesion. It is faux reality, more of a caricature than an accurate representation, of what a leader should be.

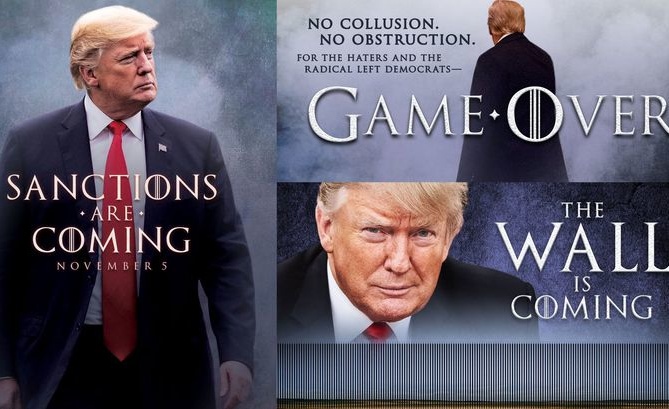

So as he appropriated popular culture for his spectacle, it is no surprise Trump’s “bragging, chest-pounding, and hypermacho posturing” seized upon the globally popular TV series Game of Thrones.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) April 18, 2019

Moments after his Attorney General William Barr misrepresented and tried to bury the Mueller Report on Trump-Russia links, Trump put out his “Game Over” homage to Game of Thrones, the fourth time he had referred to the show.

But although he almost certainly did not realize it, the tweet — an effort to reassert his patriarchal power specacularly missed the mark. For Game of Thrones is particuarly scathing about the impact of damaging masculinity.

Far from exalting the strongman, the land of Westeros is the site of downfall, the status quo abruptly shocked by the deaths of Robert Baratheon and Ned Stark. The series’ male figures try to maintain their positions by through the policing of strict identity-based norms, pushing those who do not conform to the margins of society while making the use of violence and coercion “normal”.

But they fail. Robert Baratheon’s violent death is orchestrated by his wife, Cersei, who he had long abused. Tywin Lannister, another archetypal strongman, is unceremoniously murdered on the toilet by his “imp” son, Tyrion, who he had routinely bullied and excluded. They become victims of their own self-fulfilling prophecy.

See also Game of Thrones’ Stories of Damaging and Damaged Men

The Perverse Joke of the Macho Man

Like King Robert Baratheon, Trump’s unwitting skill is in demonstrating the pitfalls of the strongman caricature. Baratheon spent money on ventures that amused him, more concerned with creating the image of a powerful leader than in implementing policies and initiatives to help his people. The same can be said for Trump.

Dancing onstage to “Macho Man” — unaware of the ironies of the song and of the Village People who made it famous — at a rally that does not adhere to guidelines over Covid-19; nonchalantly throwing masks into the audience as a perverse joke: these, at least in Trump’s mind, perpetuate the narrative that he is a brave and heroic survivor in his own mind. But they do little to obscure the social, political, and economic damage that his inability to address the pandemic effectively has caused.

The movie trailer announcement of Trump’s return to the White House from Walter Reed has been roundly ridiculed by political commentators. However, it’s a logical extension of Trump’s use of Game of Thrones memes. Tapping into his reality star persona, this is Baratheon-esque narcissism bypassing the deaths of almost 230,000 Americans.

When Trump put out “Game Over”, he was owning the supposed “haters” who accused him of working against America’s best interests. His problemnow is that the number of haters is rapidly rising, as is the sense that it is Trump v. America’s welfare.

Instead of embracing a clear strategy to deal with Coronavirus, Trump has reverted to type. At a Florida rally celebrating his return to the campaign trail on 12 October, he doubled down:

I went through it, now they say I’m immune. I feel so powerful. I’ll walk into that audience! I’ll walk in there, I’ll kiss everyone in that audience.

The language projects power, infallibility, and the idea that he’s owning Covid-19. He isn’t. Instead, his own condition and treatment is shrouded in secrecy, while the damage to the economy and the health of the American people is there for everyone to see.

Donald Trump’s obsession with strongman politics may have assisted his election in 2016. It may have sustained his base during his term in office.

But it also proved his undoing. A leader’s self-image means precious little when the illusion of hope fades.

Ultimately, Donald Trump was unable to change the narrative. The would-be strongman has fallen, losing the election to Joe Biden by a 306-232 margin in the Electoral College and by more than 6 million votes.

Like Robert Baratheon, Trump has discovered — even if he doesn’t realize it yet — people tend to turn on you when you ride roughshod over them.