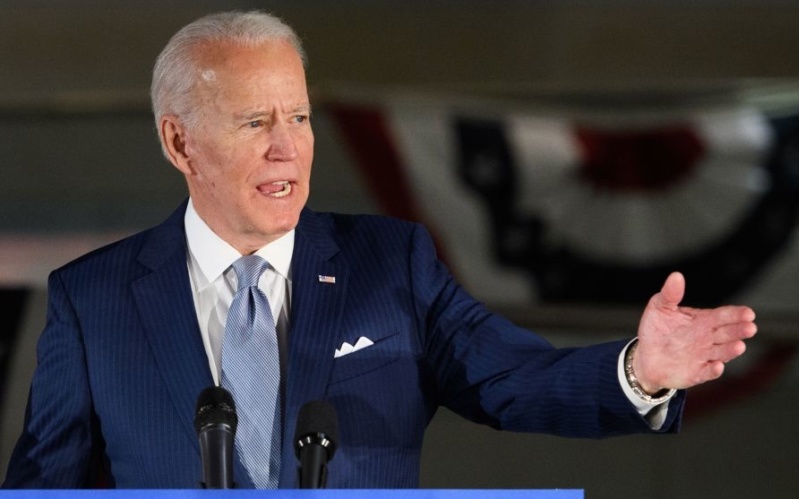

Joe Biden speaks at the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, March 10, 2020 (Mandel Ngan/AFP/Getty)

Draw the curtains. On to the next show.

After another multi-state vote in the Democratic Party Presidential primaries on Tuesday night, the contest is over as a competitive event. Barring a health emergency or unforeseeable meltdown, Joe Biden will be the nominee facing Donald Trump for the White House this autumn.

This was a sequel to Super Tuesday, with a series of victories setting up Biden’s endgame advantage over Bernie Sanders.

See also EA on Al Jazeera English: Super Tuesday, Biden v. Sanders, and Confronting Trump

Super Tuesday Analysis: How “Comeback Joe” Succeeded — and Can He Succeed Again?

Sanders had put his hopes on Michigan. He won it in 2016, in a big polling upset over Hillary Clinton, and the surprise gave him enough of a boost to pursue his challenge for months despite always being the underdog. This time, Biden won 53% to 37%.

While this was only one state, the risk of investing all your chips there is losing the big bet. Now the narrative is Bernie Going, Going, Gone? rather than Bernie Fights On.

Comeback Joe’s Winning Combination

Biden won — or, if you prefer, Sanders lost — for three key reasons:

First, unusually extreme polarization by voter age favored the former Vice President.

The plan of the Sanders campaign to capitalize on intensive support from younger voters. The victory by landslide among under-30s, and sometimes by under-40s, continues. But these voters are turning out less than their seniors. The pattern continued on Tuesday: there was an increase in participation, but it was driven by older voters.

Second, Biden continued his surge on the back of strong African American support. The pivot of the contest was the South Carolina primary on February 29, when the African American vote revived Barack Obama’s Vice President from near-fatal showings in Iowa, New Hampshire, and Nevada. When he won almost 50% of South Carolina’s vote, it closed the remaining campaigns — notably Pete Buttigieg and Amy Klobuchar — in the “moderate” lane, allowing Biden to consolidate support among those looking for a message different from that of the Sanders “revolution”.

Other former hopefuls joined in: Cory Booker endorsed Biden, and Kamala Harris — being mentioned as a possible Vice Presidential running mate — went further with a headline social media campaign alongside Joe. Voters could back Biden because he reflected their own views and/or because they think it’s the best strategy for the overriding priority of defeating Donald Trump.

African American voters tend to be both more institutionally committed to the Democratic Party and more moderate or conservative ideologically, compared to white Democrats. So Sanders’ advocacy of “political revolution”, condemnation of the “Democratic establishment”, and badging as a “democratic socialist” may have boosted him with young, white, progressive activists, but it likely distanced him from African American voters. Bernie won a majority among the youngest African Americans at the polls, but there were not nearly enough to match Biden’s supporters.

Third, leading figures in the Democratic Party have moved swiftly to consolidate behind Biden after South Carolina, a victory which owed much to the endorsement of the state’s US Rep. Jim Clyburn. Buttigieg and Klobuchar’s withdrawals on the eve of Super Tuesday, with a rally appearance to back Biden, were vital. Harris, Booker, Beto O’Rourke, and former Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid added momentum.

If you think the Democratic Party is a malign institution which rigs the system against the triumph of left-populism, then this mobilization confirms your worldview and inflames your sense of grievance. Alternatively, if you think it’s a core purpose of political parties and their leaders to send clear cues to supporters about what is best for electoral interests, this is the political system working exactly as it should.

Either way, the outcome highlights a major risk for any uncompromisingly anti-establishment campaign. It is almost certainly correct — especially these days — that you can make hay with a message that the party which you want to take over is rotten, that those who oppose you are pusillanimous or corrupt, and that the mission is not just to win the general election but to purge the enemy within.

But the downside risk is that you will be heard clearly by those who *disagree* with you about all that, and they will be counter-mobilized to oppose you. If there are more of them, that’s a problem.

Sanders had a starting game plan to win 30% to 35% of the vote in a field where the internal opposition was divided, then leverage that into getting the nomination. When it became a straight fight against Biden, the strategy failed. The belligerence of some of Sanders’ most intense online supporters may not have swung the overall contest, but it hindered him in expanding his coalition, winning over other candidates and their supporters when they dropped out. An already narrow electoral path became a dead end.

Forward to Uncertainty

It is striking how much unwarranted certainty is being put out on US airwaves after Biden’s ascendancy, from partisan observers of all stripes.

Donald Trump is neither assured re-election, nor stumbling into certain defeat. Sanders would have been a risky nominee but not a guaranteed loser, even if the demographic numbers in the primaries make it clear his electoral strategy has been premised on some unconvincing assertions. Biden has well-known weaknesses, but can win the general election on a message of centre-left policy and institutional “return to normalcy”.

If Biden loses, there will be plenty of recriminations among moderates about why a vulnerable, old, status-quo-ante figure was able to lock up the Obama legacy nomination when others might have done better with it. But if he wins, many of the same people will wonder if the victory should have been in 2016: even running at his diminished speed, and with a tougher field of competition, he’s outperformed Hillary Clinton in shutting out Sanders. Joe doesn’t need to outperform Hillary by that much in the general election to beat Trump.

Win or lose in November, the progressive movement within the Democratic Party isn’t going away, even if Sanders has limited time left on the stage. Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez helped save Bernie’s campaign with a vital endorsement after Sanders’ heart attack in the autumn. She’s in a prime spot to inherit his infrastructure and keep making the case that the status quo embodied by Biden is out of time, and that the country needs bold measures of change.

The future of the Democratic Party, and perhaps the nation, will hinge on whether those overwhelming young-voter majorities for the progressive left maintain their views as they age and become the majority of the party — or if, like some other generations, their politics shifts and new events shape their worldview.