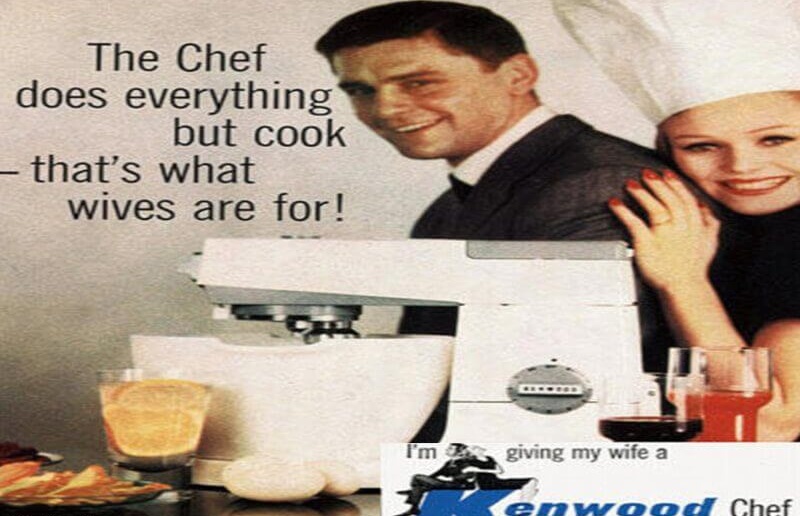

An ad for a Kenwood food processor in the 1960s — have we moved on?

Originally published by the Birmingham Business School Blog:

This month new advertising laws, prompted by the UK’s Advertising Standards Authority, have been instituted after a review of gender stereotyping.

Under the new rules, traditional gender-role stereotypes are not banned, but “harmful” or “offensive” depictions, such as those outlined by the Committee of Advertising Practice, will not be permitted. These include scenarios of men battling with household chores or girls portrayed as less academic than boys.

Last year, the ASA posted the UK’s top 10 most complained-about ads of 2017, which they said were “misleading”, rather than agreeing with the public’s complaints that they were “offensive”. Still, it is one thing to criticize an ad, such as the one used to promote a new toilet air-freshener, for highlighting that even Hollywood stars need to use the bathroom — and quite another to challenge ads for perpetuating outdated gender stereotypes.

How did some of these adverts make it to air? What was the screening process like and who was in control of these checks? What is needed here is for organizations to become more socially responsible and aware of any potential negative reinforcing stereotypes – the envisaged outcomes of these new ASA rules.

Folgers Coffee ads from the 1960s

Rather than excessively focusing on “what is and is not deemed as offensive”, these new rules acknowledge society’s increasing awareness, especially in our #MeToo era. While adverts are still over-reliant on placing people in gender-typical roles to be whimsical or seek some sort of comedic effect, they are a stark contrast with their predecessors, demonstrating how far society has come in terms of gender equality. The empowerment of women and the willingness of fathers to be more hands-on with their babies and children is becoming increasingly apparent.

The media is now starting to pay attention to these changes: depicting men in “softer” and more egalitarian roles and targeting women through pro-female messaging – ‘femvertising’ – for example, the #LikeAGirl campaigns by Always. A recent comparative study across the UK, Poland, and South Africa found that audiences preferred advertisements which portrayed men in non-traditional, paternalistic house-husband roles, as opposed to the traditional ‘envious’ businessman.

Celebrating, rather than objectifying, women in advertising while dismantling gender-equality barriers makes business sense. Now a central consideration is creating ads which are authentic and not simply companies playing the “femvertising” card to increase sales.

Any step towards reducing harmful one-dimensional stereotypes is positive; especially as new studies reveal that “housework is still considered women’s work”. Let’s hope that these new regulations pave the way for a greater push for gender equality in society and the extinction of rigid and archaic gender stereotypes.