“Unless structural and political causes are targeted by radically alternative policies to reheated Thatcherism, the UK’s low pay problem will continue to persist.”

Professor Tony Dobbins writes for the Business School Blog and The Conversation:

The Low Pay Commission estimates that approximately 2.4 million workers in the UK received close to a 5% rise in the National Living Wage from April 1. The statutory national minimum wage for workers over 25 will increase from £7.83 to £8.21 per hour, and workers under 25 receive lower National Minimum Wage rate rises.

The government has set a target for the NLW of 60% of median earnings by 2020, depending on economic conditions. Given that the Conservative Party — now in power — opposed the minimum wage when Labour introduced it in 1998, it is a remarkable transformation that Chancellor Philip Hammond now endorses levels for the minimum wage that rival the highest international comparators.

Defying the NLW’s critics, job losses have not yet happened, although the hidden “informal” economy has grown. Counter-arguments that minimum wages stimulate increased employment demand, through more disposable income for the low-paid, are better supported.

However….

But the NLW is arguably not a real living wage. Conservative Party policy focuses on it as a single economic measure to raise living standards, yet it is insufficient as a stand-alone silver bullet. Moreover, the NLW is undermined by other “anti-worker” policies that reduce living standards and increase inequality.

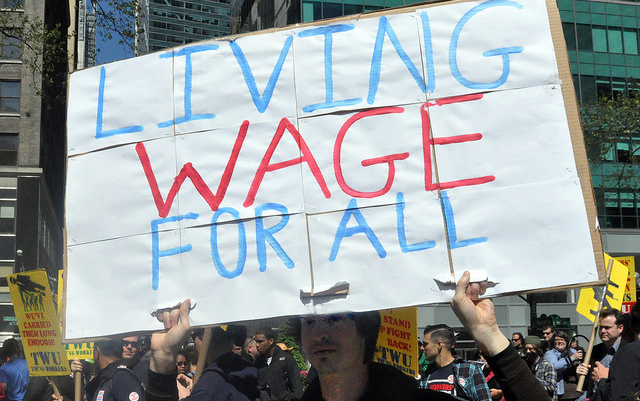

1. Statutory minimum wages are inadequate to address working poverty and living costs. Through the Living Wage Foundation, the civil society organisation Citizens UK has introduced a Real Living Wage. This is set by calculating what workers need to cover basic living costs.

The voluntary RLW is higher than the rebranded NLW introduced by Conservative Chancellor George Osborne in 2016. In May 2019, the RLW increases by 2.9% to £9 an hour outside London and 3.4% to £10.55 in London. More than 4,700 employers pay it and are LWF-accredited as morally and ethically responsible businesses.

2. Legal minimum wages are insufficient for many people to get by, given inflated costs for essentials such as housing, energy, and transport – largely attributable to privatized and outsourced public services. This has been compounded since 2010 by austerity and welfare cuts, including the Universal Credit debacle. Raising minimum wages to tackle working poverty is like placing a small plaster on an open wound when the welfare state and public services are being eviscerated.

3. Low pay is symptomatic of deeper systemic deficiencies within the UK economy and poor comparative productivity. Cost competition dominates business strategy; most notably service sector employers with large numbers of poor-quality, low-skilled jobs. Job quality, not just quantity, needs attention. The UK badly requires proper regional industrial strategy, not only encompassing manufacturing but also a Green New Deal and the foundational economy.

4. Minimum wage legislation only establishes an individual minimum floor — indeed, many employers interpret it as a pay ceiling. Collective bargaining and other wage determination institutions like Wage Councils need strengthening and rebuilding at workplace, sector, and national levels. Most workers do not have enough power to bargain wages above the legal minimum.

Statutory minimum wages are vital for regulating low pay but do not provide a real living wage. They are a response to symptoms of embedded inequalities caused by deeper underlying structural conditions and political choices associated with “trickle-down economics” and neo-liberalism.

The UK is increasingly positioned as a low-tax deregulated market economy. Unless structural and political causes are targeted by radically alternative policies to reheated Thatcherism, the UK’s low pay problem will continue to persist.