Brexit-ers Boris Johnson and Michael Gove (File)

“Whatever the outcome of the Brexit process, women’s exclusion from the debate about the UK’s future in Europe demonstrates that they have limited opportunities to participate as active citizens.”

Dr Charlotte Galpin will be speaking on “Diversifying the Brexit Debate: the EU and Marginalised Voices” at the University of Birmingham’s ESRC Festival of Social Science on November 7.

She writes, in an analysis originally published by The UK in a Changing Europe:

Recent reports have highlighted the likely negative economic impact of Brexit for gender equality in the UK, with The Fawcett Society and Women’s Budget Group finding that women will be hit hardest. Women’s rights in the workplace will be put at risk as protections guaranteed by European legislation are removed.

This effect is particularly problematic given that women did not have a prominent place in the referendum campaign, making up only 15% of people appearing in campaign press coverage.

So is the marginalization of women specific to the referendum, or is it a longer-running trend in EU debates? As part of a larger research project on media negativity, I explored women’s participation in news coverage of the 2014 European Parliament election. The UK’s membership of the EU was a key issue in the campaign, after Prime Minister David Cameron’s 2013 promise to call an in/out referendum if the Conservative Party won the next general election.

To get a broad sample of press coverage, I collected articles over a three-week period from The Guardian, The Daily Mail and The Telegraph, three of the most widely-read online newspapers in the UK. I analyzed women’s participation in the debates at three levels: as journalists writing news about the European elections; as speakers – political actors or expert sources – quoted in the news; and as commenters in discussion threads underneath articles. I examined both their overall numerical presence in the debate, and their opportunities to express their diverse experiences and perspectives about different levels of government.

There are three dimensions of debates. Firstly, they may involve the shape of particular policies or regulations, such as EU monetary policy or national immigration policies.

Secondly, debates may revolve around politics: party competition, the personal qualities of candidates, or questions about who wins or who loses an election.

Thirdly – and this is particularly relevant to European elections – debates can relate to polity. Here questions about political systems or institutions are relevant – in this case, it may refer to expanding or limiting the EU competences, its democratic legitimacy, or a country’s membership of the EU overall. EU polity contestation refers to these broader debates about European integration.

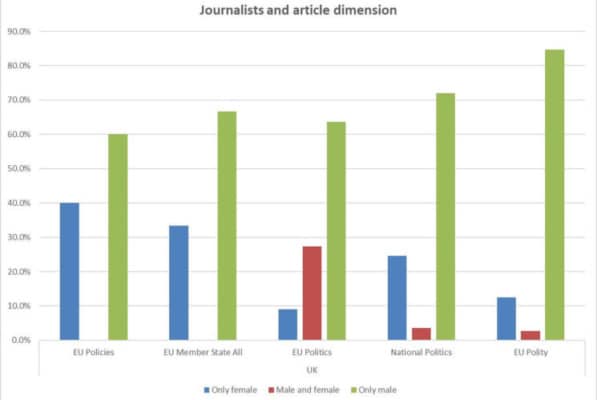

While women were marginalized in European Parliament election news across the board, they are marginalized to a greater extent in debates about the EU polity. Generally, female journalists are underrepresented when writing political news – research has found around a third of political news articles in Europe are written by women. But during the European election, women wrote twice as many articles about EU or national politics than about the EU polity.

Just over a quarter of articles about EU politics – for example, issues related to parties in the European Parliament or the appointment of the European Commission President – were written by female journalists in collaboration with male colleagues. An additional 9% were authored by women alone.

Women writing alone authored a quarter of articles about national politics. However, female journalists writing alone authored a mere 12% of articles about the EU polity, demonstrating that they had very little stake in shaping the news about European integration or the UK’s EU membership.

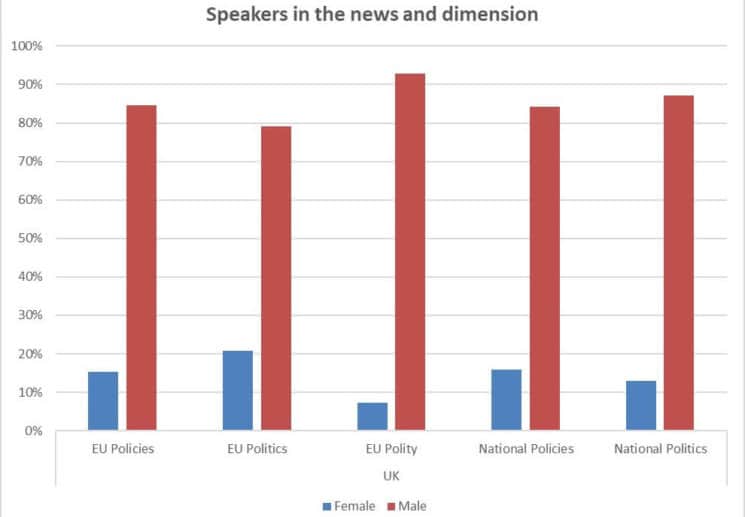

This pattern is broadly replicated amongst politicians and expert speakers quoted in the news. More than twice as many women are quoted speaking about EU politics than EU polity (20% compared with 7%), and more also speak about national politics, though the figure here is also low (12%).

Women are therefore far less likely to participate in debates about European integration or the UK’s EU membership than they are to be quoted speaking about partisan issues in the European or British parliaments.

If we look closely at the women who are quoted speaking about the EU polity, the 7% amounts to eleven quotes by women. Of those, nine were foreign women, seven were from radical right parties (of whom five were France’s Marine Le Pen), and only two were British politicians – Conservative MP Margot James and Margaret Thatcher.

So female politicians and experts in the UK were almost entirely excluded from debating European integration during the 2014 EP election. Those women whose voices were heard tended to be far-right, Eurosceptic, and/or fo”eign.

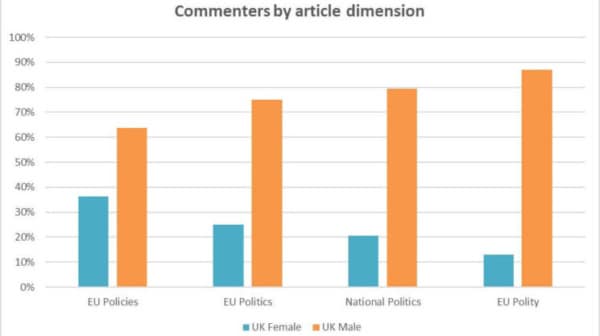

Of those users commenting “below the line” who identified with a gender through their username, women were more likely to discuss articles about national (20%) and EU politics (25%) than the EU polity (13%). This suggests that online discussions about European integration are less inclusive than discussions about party politics and that, generally speaking, women do not participate openly in conversations about European integration.

Overall, At a moment when the UK’s membership of the EU was highly politicized, women in the UK were excluded from the process of debating the UK’s future in Europe.

Why is there a gender gap when talking about the EU polity? It is partly a reflection of the male-dominated nature of the formal political sphere, especially in relation to EU affairs: in 2014 there were no female leaders of the major political parties, no female Parliamentary spokespersons for EU affairs, no female chairs of EU-related select committees, nor did we have a female foreign secretary or Europe minister.

Despite now having a female Prime Minister and more female MPs in Parliament, not much has changed – the Brexit process has primarily been overseen by men. Few female politicians therefore have responsibility over our relationship with the EU.

There is also a lack of inclusiveness in the wider public sphere and civil society that marginalizes women from debates about the EU. Women are more likely to face hostility when speaking about EU membership – Gina Miller has openly discussed the racist and misogynistic abuse she has received since challenging the government on the trigger of Article 50.

In a forthcoming article, Roberta Guerrina, Simona Guerra, and Theofanis Exadaktylos find that the referendum campaign failed to activate women: the campaigns did not address gender equality or social policies and women reported feeling less confident about their knowledge of EU affairs.

European integration has proved to be a masculine domain from which women are sidelined at all levels, despite the fact that Brexit will have very real implications for women. Whatever the outcome of the Brexit process, women’s exclusion from the debate about the UK’s future in Europe demonstrates that they have limited opportunities to participate as active citizens.

Going forward, we need to build a more open and inclusive public debate about the big issues facing this country.

What a savage misogynistic place the UK is. All the more reason to hurry up and kick them out of the EU ASAP.