“Nothing is secret anymore. All of you are thieves. Count them with us and see what the good thing you did for us was? How did you rule us? If the entire nation wakes up, your life will turn to darkness.”

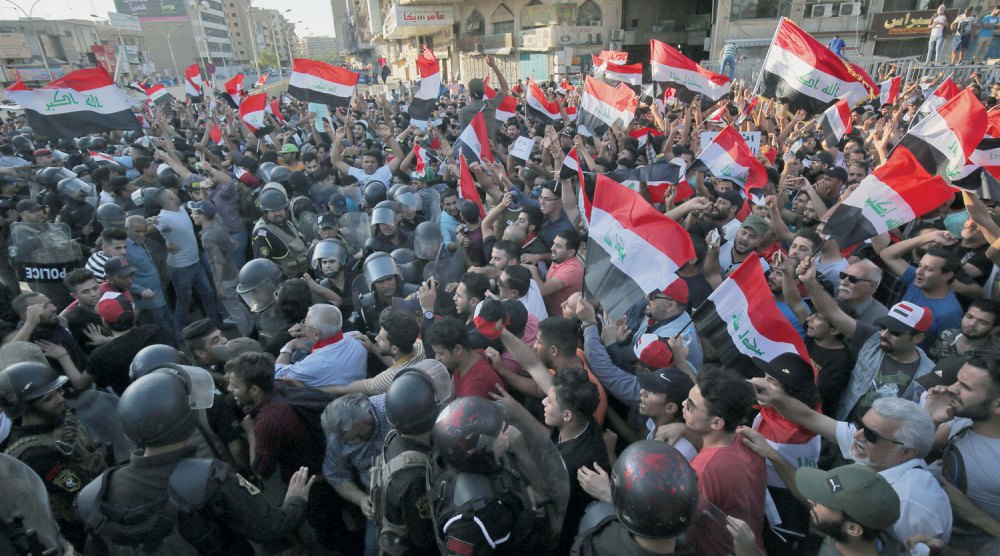

These are the chants of Iraqi people in their latest protests, starting from second city Basra and then spreading across the south of the country and into Baghdad.

While people are demonstrating over poor public services, they are sending a message to the ruling parties: we have had enough and we have lost faith in you.

This is the second time that the message has been delivered. Two months ago, the majority of Iraqis decided to boycott the parliamentary elections, indirectly telling the Iraqi Government and the world about their disillusionment with the all the participating parties, who maintained the status quo through an unjust election law and a quota system.

But this time, the point is being made directly. This is a rising against the political system as a whole, represented by all ruling parties.

Basra: The Starting Point

Basra mirrors all the contradictions of post-2003 Iraq: vast resources, potential, and history yet a miserable reality. Described as al-Fayha (a spacious place), Basra is Iraq’s wealthiest city in oilfields and the country’s only port as it borders Iran and Kuwait on Shatt al-Arab, the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. It is one of the main sites for palm and rice production, among other crops.

Basra’s historical significance dates to the pre-Islamic era. It was the birthplace of pioneer Arab linguists, including al-Jahidh, and Al-Farahidi, who laid the ground for Basra’s grammar school, and of great Iraqi poets such as Badr Shakir al-Sayyab. But today’s Basra is high unemployment, salinity in water, abysmal electricity, militias, drugs, trash, and no proper educational or health system. Factions fight for the oil revenues to extending their power and control.

Basra is not unique. All Iraqi cities are beset by the problems, an outcome of a political culture immersed in corruption, patronage, and nepotism. But Basra is likely to be distinctive: as in 2015, it is igniting the flame for protests in the south and the capital. However, this time — unlike 2015, when Shia parties and their militias hijacked Baghdad’s protests — Basra is likely to remain the center.

Who Are the Protestors?

The protestors in the streets in the south and in Baghdad are ordinary, simple people. Many of whom are youth who found themselves jobless after graduation, or poor who live under dire conditions. Many have lost a son, brother, a father, a relative, or a friend in the fight against the Islamic State. They stress their “Iraqiness” as opposed to political leaders, whom they see as loyal not to Iraq but to an interfering Iran. Despite being mainly Shia Muslim, they do not have ties to political leaders whom they see as expressing fake sanctity. People no longer feel they share their national or religious identity with these leaders and so cannot subscribe to the old narratives of victimhood, sectarianism, and the legitimacy to rule.

Unlike previous years, these protests lack a coherent leadership. Neither the liberals nor the cleric Moqtada al-Sadr are in front. People are spontaneously, organically, and peacefully protesting with no agendas.

Following the killing of a protestor in Basra, people stormed council buildings and burned party headquarters, an unprecedented action. This was not an act of vandalism or deliberate sabotage of public properties, but the expression of an accumulated anger against parties and their militias. In Najaf, when protestors stormed the international airport, it was because parties, complicit in financial corruption, were running it. Acting Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi ordered the dissolution of the airport’ board of directors, bringing the facility under the control of the federal government’s civil aviation body.

The protestors are neither infiltrators nor Baathists, as they are tarnished by the government and party leaders echoing the rhetoric of Saddam Hussein’s regime.

However, lacking leadership, the demonstrations have a vacuum that can be exploited by parties, tribes, or other actors, leading to more chaos or problems.

Neo-Dictatorship

The protests were met with oppressive measures by the government. Security forces were sent to the south, under the pretext of protecting oilfields, government buildings, and parties’ offices, to quell the protests. Militias protecting party headquarters, as well as members of the security forces, opened fire and killed 13 people and wounded hundreds. Witnesses said some protestors were chased and beaten with baton, hoses, and cables. Tear gas and water cannons were used to disperse the crowds. Hundreds of activists were arrested — some released on bail, some still missing.

On July 12, internet was cut off across the country, isolating Iraqis from the rest of the world. The 3G network was restricted, and there was a news blackout in national media outlets. When the internet was unblocked, the Ministry of Communication justified the shutdown as a technical fault due to cable cuts. Later Minister of Communication Hasan al-Rashid admitted that the cutoff was deliberate because social media sites were “misused” during the protests. The signal remains very weak and social media platforms are blocked. (Meanwhile, to Iraqis’ amazement, their leaders can still tweet and post on Facebook.)

To contain the protests, Abadi met in Basra and other province with some tribal leaders, whom the protestors do not regard as their representatives. The Prime Minister allocating 3.5 trillion Iraqi dinar ($3 billion) from the government’s budget, which already suffers from a deficit of $10 billion to Basra, saying that would provide 10,000 job opportunities. The unplanned and inefficient policies could complicate rather than resolve matters: the Ministry of Planning in Basra says they expect half a million applicants for the 10,000 jobs. The Council of Ministries has issued six decisions to address the demands of southern provinces, possibly setting up a “crisis cell” within each ministry to detect the needs of people — 15 years after the overthrow of Saddam Hussein. The decisions vaguely describe what needs to be done without details on how and when things will be implemented.

The protests may be suppressed, but they are likely to recur. Far from addressing the causes, MPs recently attempted in secret to pass a bill to increase their benefits and privileges. (The effort was eventually blocked by Prime Minister Abadi.)

As one protestor says, “Please listen, the issue is that of a homeland, is that of Iraq stolen from us. We want Iraq back.”

This is more than just anger over poor public services; it is about a homeland. Without reforming the base on which the Iraqi state stands — constitution, elections, laws, and a quota system — Iraqis will be stuck in a cycle of discontent and disservice.