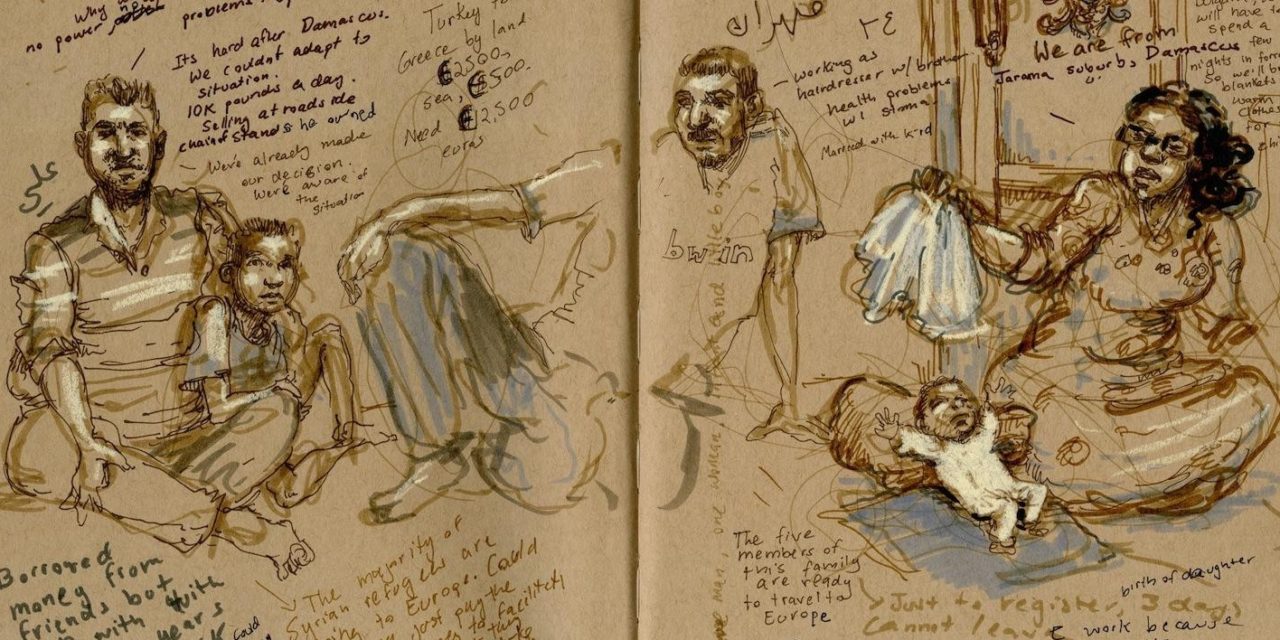

PHOTO: Molly Crabapple’s drawing of Syrian refugees in a camp in northern Iraq

Lina Sergie Attar is a US-based Syrian writer, aid worker, and architect based in Illinois. She started the Karam Foundation in 2007 to aid displaced Syrians in need, offering food, health care, education, and leadership courses. At two of Karam’s schools in Reyhanli, Turkey, just over the Syrian border, Attar hosts Zeitouna, a creative therapy and wellness program for Syrian children, that uses art and self-expression to counter the impact of trauma.

One of the program’s mentors is American artist and writer Molly Crabapple, author of the memoir Drawing Blood.

The two draw on their experiences to talk about the importance of Syria’s refugees, learning and preserving their stories, in an article published by Good:

Attar: Last year, for our leadership program for Syrian refugee teens in southern Turkey, we built them a computer lab and prepared courses in coding, entrepreneurship, technology, chess, sports, and art. We had a journalist with us, Hala Droubi, and the kids kept asking her, “Who are you? What do you do?” When she told them she was a journalist, they asked her to teach them.

As somebody who grew up in Syria, that’s very foreign to me. Journalism was not a space that people aspired to work in. There was no freedom of speech. It took very courageous journalists —most of whom ended up in prison — to do any honest and truthful writing. But this generation of Syrians, they’re very different. They’re watching themselves grow up on YouTube, watching stories of their country on the news. I think journalism appeals to them because, now, they can tell their own stories.

Crabapple: Syria is perhaps one of the most recorded, portrayed conflicts in the world, and yet, in English-language media, there’s a real dearth of Syrian voices. It’s so important that Syrians are speaking for themselves as opposed to having a lens put on them by Westerners.

Attar:: It’s very hard for me to speak about refugees to American audiences. First of all, there aren’t many Syrian refugees in America, only around 2,000. The number is minuscule in comparison to all of these stories about Syrian refugees who’ve come here, but [the media] ignores the millions that weren’t able to come.

Molly, the most powerful thing about your pieces are that you use the lens of your art, but you’re also giving the voice to a Syrian citizen. I’d like for you to talk about that — the merging of art and journalism is something very special in your work.

Crabapple: You’re talking about my collaboration with a young Syrian writer, Marwan Hisham, who I’ve known for some years now. He took surreptitious photos of life around Raqqa on a cell phone. There were these few that weren’t the usual gory-torture-death-porn shots that ISIS is usually portrayed with in the media. It was little kids looking through trash for objects of value to sell, or people waiting in bread lines. They were things that really captured the poverty and shrinking of public space there. They were astounding photos, so I drew from them and Marwan wrote captions.

This past summer, I spent some time in Shuja’iyya, which is the neighborhood the Israelis fought in during Operation Protective Edge when they invaded the Gaza Strip. There were these decimated buildings, and all this twisted, melted rebar from a hospital that Israel had bombed. People were straightening it out to make it into new building material. It looked like snakes — so malignant and coiled. I was so struck by it. One of my favorite pieces I ever did was of these guys straightening the rebar. I try really hard to filter out the inessential in my work to portray the things that I think are the most powerful and true.

Attar: I feel like everything I’ve wanted to say has already been said, especially in terms of my work as a writer. It used to be so immediate, like I would hear any story and say, “People need to know this. People need to know what’s going on in Syria because they don’t, and if they did know, then they would stop it.” That feeling, that urgency to tell stories in real time, as fast as I could, faded as the crisis became a war.

The scariest part about the Syrian narrative is that there’s an active erasure of the beginning, of why this started. ISIS [the Islamic State], the refugee crisis, and the political opposition smother the beginning. I don’t want people to forget why it happened. So many people have disappeared, so many people are dead—and many of them were my friends. That part of history will be erased unless we are all working to keep it recorded somewhere. That’s where I feel our work is, in between memory and history.

Crabapple: It’s so important because the truth is those people, those original revolutionaries, those original protesters aren’t convenient to anyone. They shame the entire world. And so everyone, every side — America, Russia, Assad — everyone wants to forget that they ever existed because they’re a thorn in all of their memories, a reminder of the ways they failed. Preserving their memories is so vital.

Attar: e never had a chance to process it all. We’re always onto the next big thing, the next big crisis, the next big story. Everyone wants to speak for Syrians, to write on their behalf.

Yesterday, my friend was telling me, “I remember when I was in high school, nobody even knew where Syria was on the map.” A lot of times I wish people still didn’t.