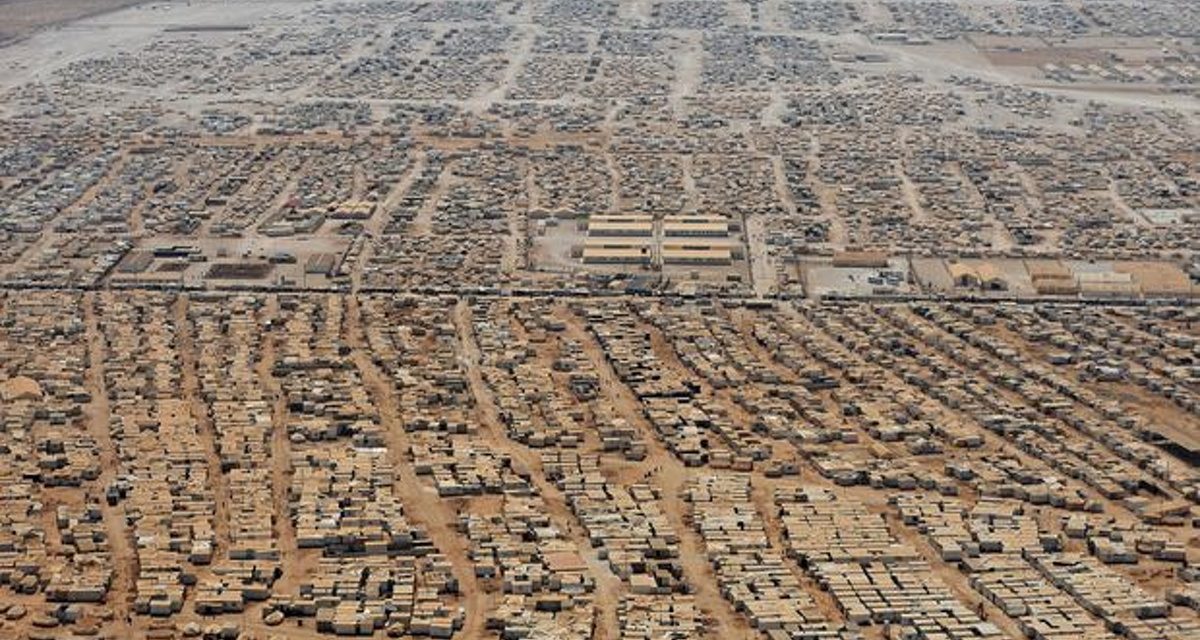

PHOTO: Jordan’s Zaatari refugee camp

Mark MacKinnon writes for Canada’s The Globe and Mail about Syrian refugees in the Zaatari camp in Jordan.

There are more than 630,000 registered refugees in the country. International assistance, such as food vouchers, has been cut this year because of funding shortages.

The first time I met Halim Mahameed, he told me of how he’d been tortured for two straight days by Syrian security forces. Almost robotically, the then-14-year-old recounted how he’d been tied up by Bashar al-Assad’s men the previous year and whipped with electric cables because he’d been seen helping to carry the wounded away from an anti-regime demonstration in the early days of Syria’s conflict.

Things should have gotten better for Halim after we met in the fall of 2013. He was then in a Unicef-run school in Jordan’s sprawling Zaatari refugee camp. And while some were already warning of a traumatized “Zaatari generation” growing up angry among the four million Syrian refugees scattered around the Middle East, the case workers who introduced me to Halim said he was a success story in terms of how well he was mentally processing the ordeal he’d been through in Syria.

But the world ignored the warnings. And life has gotten worse for the Zaatari generation.

When I returned to Zaatari for two visits earlier this month, I sought out Halim Mahameed among the maze of metal caravans and canvas tents in the Jordanian desert, hoping to find out what had happened to him since our first meeting.

To my dismay, he was no longer in school. His family, which like many Syrian refugees around the region has struggled to make ends meet as food stipends and other international aid dwindle, pulled Halim out of the UNICEF classroom last year and found him a job working alongside his father in one of the Jordanian farms outside the gates of Zaatari.

He makes one Jordanian dinar — about $1.40 — an hour picking olives and tomatoes. He’ll likely never see the inside of a classroom again.

“My dad’s back was hurting, so I started going to work with him. Now our financial situation is better than before,” Halim says with a shrug.

His face – still marked with traces of the scars given to him by Mr. al-Assad’s thugs – is expressionless as he speaks. It’s black-and-white to him. The family had no option. He claims he didn’t like school anyway, and says he can envision no other future.

Halim’s father, Hayyam Mahameed, lays out the economics behind the family’s decision. As Halim’s twin three-year-old sisters grew older and started eating more, the family started running through the $141 a month they receive from the World Food Programme faster and faster. Mr. Mahameed says the WFP aid now lasts the family of five “about 10 days” in Jordan, where food costs are high.

“When Halim left school, it was a stab in my heart, but he had to leave,” says 47-year-old Mr. Mahameed, who worked as a salesman in the southern Syrian province of Daraa before war broke out in 2011. “Before the war, we were paying for Halim to get extracurricular education. He’s my only son.”

Losing a Generation

The Mahameeds’ story is sadly common among both Zaatari’s 79,120 residents, as well as the wider Syrian refugee population scattered through Jordan, Lebanon, Syria and Iraq. Of the 4.3 million Syrian refugees in the region, 51% are kids age 17 and younger; 38% are under the age of 11.

Despite all the warnings of a generation growing up in desperation –– and the troubles that could cause for the Middle East and the world – the international community came up with only 45 per cent of the $4.5-billion that United Nations agencies asked for to meet the basic humanitarian needs of Syrian refugees in 2015.

The shortfall has led to falling WFP food aid –– the monthly stipends received by many refugees have fallen by half or more in the last 12 months –– as well as a lack of classroom space for refugee children around the region.

Between Jordan, Turkey and Lebanon, there are an estimated 700,000 school-age Syrian kids who are not in classrooms this year. Part of that is a simple lack of schools. But the economic crunch is also playing a big role.

Boys are leaving school so they can take menial jobs to earn money for their families. Girls are having their educations cut short so they can be married off at younger and younger ages, thus reducing the number of mouths a family has to feed. Begging Syrian children – both during school hours and late into the night – are now common sights on the streets of Middle Eastern cities.