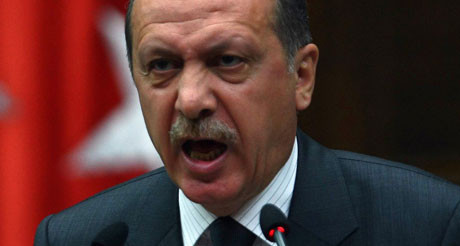

PHOTO: Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan

Ali Yenidunya of the University of Birmingham writes for EA:

Hundreds have been killed in clashes between Turkish security forces and the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) since 7 July. Furious Turkish nationalists have attacked people because of their skin color and use of Kurdish over the phone as they walk on the streets. Turkish officials intentionally use acrimonious language against anyone who oppose operations against “terrorism”, and they encourage the Turkish nationalists to support their “holy fight”. Fathers who praise the State as they mourn their fallen sons receive official thanks; those who criticize are targeted by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

Some may wonder how bad the situation could get. Well, not much can be worse than a situation where there is no information from besieged towns because of military restrictions. The province of Cizre in southeastern Turkey has been cut off for almost two weeks. Civilians killed by snipers, unable to be buried, are kept inside freezers. The head of the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) and other MPs and activists are prevented from entering. The Interior Minister, Selami Altinok, says 32 people — including a baby and a 7-year-old girl — have been killed so far, but Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu denies that the people of Cizre cannot meet their daily needs and says bakeries are still open.

See Turkey Feature: A Country “Increasingly Drifting into Civil War”

Why is President Erdoğan insisting on this bloodshed? The answer lies in the results of June’s election, where the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) lost its majority in Parliament for the first time.

Erdoğan’s strategy was first to drag the country into an early election, which is now scheduled for November 1. He then set a goal of getting 400 loyal MPs in the 550-seat Parliament.

The path to that victory lies in an appeal to nationalism through military conflict. The AKP lost a decisive portion of the Kurdish constituency to the HDP in June election. Instead of trying to recover that, Erdoğan decided to militarise the eastern region. The PKK handed him a pretext in late July when it killed two policemen, accusing them of links to the Islamic State: the Turkish military immediately responded with airstrikes on PKK camps in neighboring Iraq, and Erdoğan declared an end to the “peace process” with the Kurds, pursued since 2012.

Now more than 20 districts, including Cizre, have already been declared as military areas in several cities so far. The HDP is warning that Turkey is “increasingly drifting into a civil war”. More Turkish soldiers are dying — including 15 from one PKK roadside bomb — as Ankara cracks down on leading media outlets as “enemies”.

If the situation continues, it is unlikely that there will be true elections in much of Turkey in seven weeks’ time. That may not matter to Erdoğan if the AKP gets its majority. But, if he wins that immediate victory, can he control the violence and enmity afterwards?