The recent military success of the Islamic State in Iraq, including the capture of the second city of Mosul, has drawn media attention to the jihadist group’s treatment of civilians.

The development has also highlighted the Islamic State’s rule of areas in northern and eastern Syria, notably the city of Raqqa, since last year.

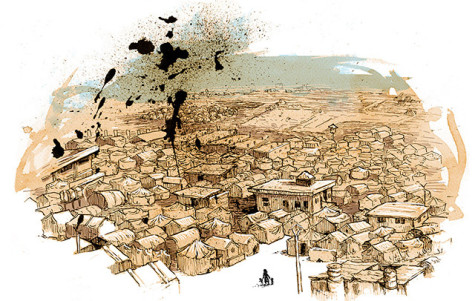

Writing for Vice, Molly Crabapple depicts the lives of Syrians who cannot leave the country: “The residents of Bab al Salam are caught between Assad, ISIS, and the random violence of the war.”

Crabapple, who visited the area with fellow journalist Patrick Hilsman, writes of numerous attacks by the Islamic State on and near refugee camps:

Walid, who said he was 11 but looked seven, had been a keen math student in Homs. He doesn’t go to school anymore. His father is dead, blown up by an ISIS car bomb. They’ve carried out two suicide attacks against the camp. ISIS has been murdering Syrians with impunity for nearly a year, bragging about their war crimes on Twitter. Now they’ve invaded Mosul in Iraq and the world cares, at least for this week.

EA reported last July on the horrific conditions within the camp, as activists and refugees in Bab al Salaam were calling for US Secretary of State John Kerry’s support. But Hilsman and Crabapple say that, with only limited action by the international community, the situation has deteriorated:

Under dusty tarps, these refugees live in horrid conditions. Barefoot kids play next to rivers of sewage. Preventable diseases flourish. The Turkish government gives out two meals a day, but the United Nations High Council on Refugees does nothing beyond providing some of the tarps. The Assad government has forbidden them from giving aid to opposition areas.

(Featured Illustration: Molly Crabapple)

Caught Between ISIS and Assad

Molly Crabapple

“ISIS are good fighters, but we fucked them,” Yusuf Halap said in fluent English.

Journalist Patrick Hilsman and I were sitting with Yusuf and two other young media activists in the Bab al-Salam camp for internally displaced Syrians, a hundred yards south of the Turkish border. Bab al-Salam houses 20,000 refugees, mostly women and children. Under dusty tarps, these refugees live in horrid conditions. Barefoot kids play next to rivers of sewage. Preventable diseases flourish. The Turkish government gives out two meals a day, but the United Nations High Council on Refugees does nothing beyond providing some of the tarps. The Assad government has forbidden them from giving aid to opposition areas.

The Saudis and the government of Qatar are showier, flaunting their generosity with branded tents. “The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia’s Gift to Humanity,” one read. The Gulf states fund fighters – their charity is marketing.

In this wasteland, young people like Yusuf are trying to cobble together a future. Before the war, Yusuf was a year into an engineering degree. When the revolution hit, his father, a higher up in the Syrian army, defected. I asked Yusuf why he joined the revolution. “They were killing women, killing children,” he said.

Yusuf works under the banner of the Islamic Front, an alliance of more-or-less religious fighting groups. The Islamic Front has successfully pushed ISIS out of much of northern Syria, including Azaz, where the Bab al-Salam camp is located. However, groups affiliated with the alliance have been implicated in their own war crimes, including murders of POWs and the kidnapping of veteran activist Razan Zeitouna.

Yusuf is 24, short and skinny with a sceptical smirk. He first picked up a gun to fight ISIS in Aleppo, where he killed two of their fighters – a Yemeni and a Tunisian, he told me, with a laugh.

When Patrick and I crossed into Syria from Turkey, we saw civilisation begin to fray. First, there were the piles of garbage. Then young people missing limbs. Then a line of cars, five days long, of families going into Turkey. Police checked them for car bombs. Some cars sat abandoned in line.

Trucks, perhaps smuggling weapons, snaked into Syria.

There were green fields on either side of the highway. Their flowers hid landmines. A group of kids, one perhaps eight, walked through the minefield. They were trying to sneak back to Syria, without papers, but Turkish soldiers goaded them back towards safety.