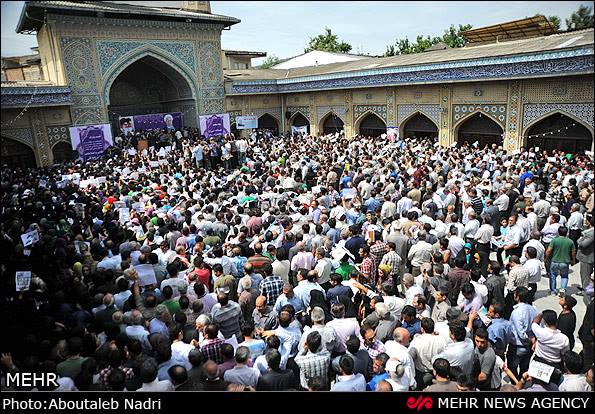

Crowd at Rouhani rally last Wednesday

Three points on the surprise first-round victory of President-elect Hassan Rouhani — and the possible significance far beyond Friday’s election:

1. THE REGIME’S FAILURE TO FIND “UNITY”

In March, we began highlighting a curiosity in the regime’s election preparations: three months had passed, and the Supreme Leader-backed “2+1 Committee” — tasked with finding a “consensus” candidate behind whom voters could rally — had failed to do so.

Because of that failure, factions within the conservatives and principlists — such as the 5+1 Coalition, the Perseverance Front, and the Epic Front — were putting forth their choices, vying for attention and perhaps the nod of Ayatollah Khamenei. Still, the 2+1 Committee dallied, with numerous press conferences but no advance in their deliberations and “sub-committees”.

The Committee said the “unity” choice would be made before the registration of candidates. Then they said it would happen before the Guardian Council approved the candidates. Then they said it would happen before the first round of the election.

The decision was never reached, however. Instead, two of the three members of the Committee — Ali Akbar Velayati and Mohammad-Baqer Qalibaf — vied for the conservative-principlist vote last Friday with another principlist candidate, Saeed Jalili, the Secretary of the National Security Council.

The lack of a single “consensus” candidate would have been only an inconvenience — after all, Velayati, Qalibaf and Jalili were all loud loyalists for the Supreme Leader — had the dithering not opened up an alternative for Iranian voters.

Encouraged by no announcement of “consensus”, former President Hashemi Rafsanjani put forward his name for candidacy, amid a flutter of publicity and excitement.

Worried that Rafsanjani might prevail, the Guardian Council blocked his candidacy, ostensibly on the grounds of “physical condition”. But that decision meant that — for the Guardian Council and the election process to maintain any shred of “legitimacy” — that Rafsanjani’s ally, Hassan Rouhani, had to be allowed to run for President.

On Sunday, the pro-regime Flynt and Hillary Mann Leverett, writing with Tehran academic Seyed Mohammad Marandi, said all of this was planned by the wise Islamic Republic: “Rafsanjani’s sidelining was a necessary condition for the rise of Rouhani, a Rafsanjani protege.” The right-wing Jerusalem Post agreed that a conspiracy had been afoot, boldly claiming that: “Rohani was purposely chosen by the Guardian Council precisely because of his ostensibly moderate views.”

Really? Don’t be fooled.

Rouhani’s victory was not a clever and cunning conspiracy, concocted by the Supreme Leader’s office. It was a popular choice, and one that was made possible by a lack of political competence coupled with an excess of division within the principlist and conservative camp.

2. ROUHANI’S CAMPAIGN OF “PRUDENCE” AND “MODERATION”

But Rouhani and his supporters still had to exploit that opportunity. They did so by a clever “balance” between assuring stability while promising change.

After Jalili’s early campaign surge lost momentum and flagged, and despite the likelihood of Qalibaf as a front-runner, Rouhani’s campaign began to grab public attention.

Rouhani was notably assertive in speeches and public appearances — unlike the other candidates, most of whom merely repeated the Supreme Leader’s lines. Careful initially to distance himself from any association with the so-called “sedition” after the disputed 2009 election, Rouhani also promised change.

This was not just the superficial change of making good after eight years of the Ahmadinejad administration’s mis-management, however. Rouhani pledged to right the sinking Iranian economy — as did the other candidates — but more importantly, he captured public attention by saying the very things that his rivals were wary of even mentioning. Rouhani opened up a discussion about engagement with other international powers, pledged to expand the scope of “freedoms” within Iranian society, and expressed anger — on air on State television — about censorship during the debates.

By the last week of the campaign, after Rouhani out-performed the other candidates in all three televised debates, thoses message were being put out to large rallies. People at these rallies then — on their own accord — went farther in their chants, calling for release of political prisoners and for a new approach to Government.

Rouhani did not dissuade them; instead, he elevated those calls.

Then last weekend came the necessary practical step: after days of manoeuvring, former Presidents Rafsanjani and Mohammad Khatami agreed to go public with their support of Rouhani as a standard-bearer. Reluctantly, the sole reformist candidate, Mohammad Reza Aref — who had also been effective in debates — stepped aside, sacrificing his chances of success for the “greater good” of a moderate-reformist coalition.

From a position of possible boycott, many reformists and followers of the Green Movement moved towards the possibility of a Rouhani Government as a space to make their voices heard. So many of them shifted from watching the election to participating in it.

3. THE LEGACY OF 2009 AND “FOUR WASTED YEARS”

Let it be said that this election was pay-back by many Iranians — pay-back to officials all the way to the Supreme Leader — for the manipulation of the 2009 vote and the subsequent crackdown to enforce Mahmoud Ahmadinejad as President.

Of course, the word “sedition” was not uttered. However, the chants in Rouhani’s crowds of “Ya Hossein! Mir Hossein!” were a powerful reminder: two of the candidates in 2009, Mir Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi, are still considered such a threat by the regime that they have been under strict house arrest for 28 months. It is not just Mousavi and Karroubi who are detained. Hundreds of activists, journalists, students, lawyers, Baha’is, and people simply caught up in the repression are also imprisoned.

Had the regime used the last four years to bring the “political and teconomic epic” that the Supreme Leader promised when he anointed Ahmadinejad in 2009, then it might have eased the pain and trauma of that collective memory. But it did not do so: Iran is in a far worse economic position since 2009, and its international standing — despite Orwellian proclamations from its supporters — has eroded, and any hope of progress had faded into resignation.

Against this background, the Rouhani campaign reignited the possibility of striking a meaningful blow against the status quo — not with violent protests this time, but with a vote that meant something.

Last week, we projected that Rouhani would make it into a run-off with Tehran Mayor Qalibaf, based on the first two reasons.

But we did not anticipate that Rouhani would do far more, winning outright. We did not see how important this third reason had become.

WHAT NEXT?

None of this indicates whether that blow, dealt on Friday, will translate into significant change. Even as Rouhani’s victory was moving past possibility to reality, the regime’s political and media outlets were trying to contain him and contextualize his win as a triumph not for the moderates, but for the Supreme Leader and the system.

This was, they said, a “political epic”, just as Khamenei had predicted, rather than a win for Rouhani specifically. Marginalized in this narrative even as he was confirmed President-elect, the message was that Rouhani would soon be put into his rightful place as a tool within the system.

However, Rouhani is not alone. The Rafsanjani machine is once more at the centre of Iranian politics. A range of clerics and politicians have offered quiet and not-so-quiet backing of the President-elect. There are other factions — with their own economic, social, and foreign policy demands — who will see possibilities in a new Government. One key figure is powerful parliamentary speaker Ali Larijani, who stayed out of the election process but reclaimed the stage on Sunday in a heavily publicized meeting with Rouhani.

In summary, Rouhani’s election as President does not herald regime change. But neither does it herald no change at all. His election will bring negotiation for influence over key issues such as the nuclear programme, “freedoms”, the detention of Mousavi and Karroubi and the political prisoners beyond them, and, most importantly, the economy. Each of those will feature different combinations of political actors — the most important, but not the all-powerful, one being the Supreme Leader.

The prospects for those negotiations will be considered in an analysis later this week.