“When you are inside, you can’t see outside.”

Ryan Lizza writes for The New Yorker:

On a recent Saturday in November, Dimitri Skorobutov, a former editor at Russia’s largest state media company, sat in a bar in Maastricht, a college town in the Netherlands, with journalists from around the world and discussed covering Donald Trump. Skorobutov opened a packet of documents and explained that they were planning guides from Russian state media that showed how the Kremlin wanted the 2016 U.S. Presidential election covered.

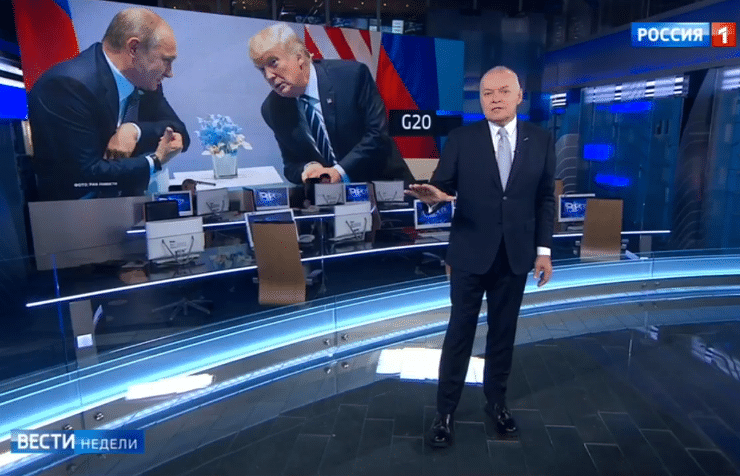

Among the journalists, Skorobutov’s perspective was unique. Aside from Fox News, no network worked as hard as Rossiya, as Russian state TV is called, to boost Donald Trump and denigrate Hillary Clinton. Skorobutov, who was fired from his job after a dispute with a colleague that ended in a physical altercation, went public with his story of how Russian state media works, in June, talking to the U.S. government-funded broadcaster Radio Liberty. The organizers of the Maastricht conference learned of his story and invited him to speak. He flipped through his pages and pointed to the coverage guide for August 9, 2016, when Clinton stumbled while climbing some steps. The Kremlin wanted to play the story up big.

Skorobutov started working in Russian state media companies when he was seventeen years old, and has worked in print, radio, and TV. During the 2016 campaign, he was an editor for “Vesti,” a daily news program. Skorobutov described it as a mid-level position, with four layers of bureaucrats separating him and the Kremlin. His supervisor was a news director who, he said, got his job after making a laudatory documentary about Putin. Before joining “Vesti,” Skorobutov worked as the press secretary of the Russian Geographical Society, a pet project of Putin, which made headlines last year when Putin declared at a Society event that Russian borders “do not end anywhere.”

In his speech at the journalism conference, Skorobutov explained that as a young journalist he believed that working for the state media was not necessarily corrupting. “When I came to TV, in 2000,” he said, in his prepared remarks, “there was another Russia: with independent media, so-called freedom of speech, with a hope for a better life associated with the new President Vladimir Putin. I was convinced that everything we do on TV is for the better life to come soon. But the life was getting worse and worse.”

Putin v. Clinton

In his telling, it was the 2011-2012 protests in Moscow that changed everything. Those protests, which Putin blamed on Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, spooked the Russian President, according to Skorobutov. “People were imprisoned. Media were taken under control of the State. Censorship introduced,” he said. “It was a point of reflection for me. The state was against its people. Human freedoms, including freedom of speech, were gradually eliminated.” (Others would note that this is a self-serving chronology, as Putin’s dismantling of democracy began long before 2011, and that Skorobutov remained at state TV through the annexation of Crimea and the war in eastern Ukraine, when Russian media propaganda was especially noxious.)

After the suppression of the 2012 protests, Skorobutov said, he became increasingly disturbed by his role in “helping the state to create this new and unpleasant reality,” resigned his job as the press secretary at the Russian Geographical Society, and began looking for a new job, but without any luck.

As is often the case with state censorship, the workings of Kremlin-controlled media, as Skorobutov described them, were far more subtle than is popularly imagined. He described a system that depended on a news staff that knew what issues to avoid and what issues to highlight rather than one that had every decision dictated to it. “We knew what is allowed or forbidden to broadcast,” he explained. Any event that included Putin or the Russian Prime Minister “must be broadcast,” while events such as “terroristic attacks, airplane crashes, arrests of politicians and officials” had to be approved by the news director or his deputy. He offered a list of embargoed subjects: “critique of the State, coming from inside or outside of Russia; all kinds of social protests, strikes, discontent of people and so on; political protests and opposition leaders, especially Alexey Navalny,” an anti-corruption figure despised by the Kremlin. Skorobutov said that he overcame censorship rules and convinced his network to cover stories only twice: for a story about a protest against the construction of a Siberian chemical plant and for one about the food poisoning of children at a kindergarten.

“Show Trump in Positive Way, Clinton in Negative Way”

During the 2016 election, the directions from the Kremlin were less subtle than usual. “Me and my colleagues, we were given a clear instruction: to show Donald Trump in a positive way, and his opponent, Hillary Clinton, in a negative way,” he said in his speech. In a later interview, he explained to me how the instructions were relayed. “Sometimes it was a phone call. Sometimes it was a conversation,” he told me. “If Donald Trump has a successful press conference, we broadcast it for sure. And if something goes wrong with Clinton, we underline it.”

Skorobutov said in his speech that the pro-Trump perspective extended from Kremlin-controlled media to the Moscow élite.

“There was even a slogan among Russian political élite,” he said. “‘Trump is our President.’ And, when he won the elections, on 9th November, 2016, Russian Parliament or State Duma even applauded him and arranged a champagne party celebrating the victory of Donald Trump.” That night, Skorobutov and his colleagues played clips of the party on the news.

In Skorobutov’s opinion, Putin’s effort to make Trump a reliable ally ultimately failed. He said that Trump’s airstrike in Syria in April ended the romance for Russian élites. “Russian authorities failed with their hopes that financial and media support will make Trump really Russian,” he said. “They were wrong as they didn’t take into consideration the US political system and mentality. Russian authorities hoped—literally—to buy Donald Trump, using bribes and tricks. But they failed.”

Skorobutov, who is back in Moscow now, told me that he left state media after a drunken colleague beat him up at work and, in his telling, the Kremlin-controlled network tried to cover up the assault. Being away from the network allowed him to think about his role as a longtime Russian-government propagandist and led him to start speaking out.

“I have to say that me and my colleagues, we didn’t think too much about censorship or propaganda,” he said in his speech. “We get used to it. As we were inside the system, inside television, inside a virtual reality. When you are inside, you can’t see outside. But I’m glad that I escaped from that wonderland, like Alice of Lewis Carroll. Better late than never.”