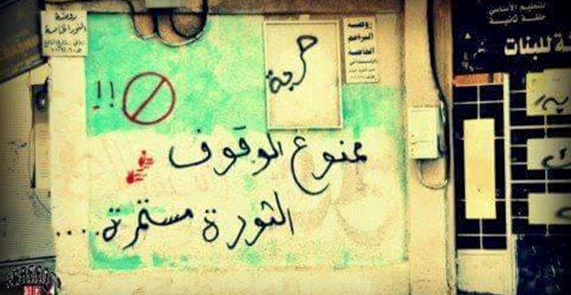

PHOTO: Graffiti in al-Tal, reoccupied by regime forces in December: “Don’t stop now. The revolution will continue”

On December 2, the Assad regime took control of al-Tal, 11 km (7 miles) north of Damascus, as Syrian rebels and their families left under a capitulation agreement.

Nicknamed the “City of a Million Displaced,” al-Tal has grown from 100,000 before the 2011 uprising to 900,000. It was beseiged since 2015.

In November, the town was given an ultimatum, according to citizen journalist Omar al-Dimashqi: “The rebels could either agree to the ceasefire, or the regime would burn the city.”

Syria Direct speaks to some of the residents, who express their regret about the capitulation:

The Media Activist

Ahmed al-Bayanuni, director of the al-Tal Local Coordination Council, an opposition media organization:

There are no guarantees with the regime, which plays by the rule “either you’re with me or against me”. As soon as the fighters left, [officials] began asking for men who reconciled with the regime to join the reserves. More than 30,000 residents are now wanted for reserve service.

Two days after fighters left for Idlib and the regime officially entered the city on December 10, security forces stormed opposition headquarters and residential buildings. They established checkpoints. They ordered the closure of all small roadside stands, which many residents rely on to make a living. They also ordered the removal of revolutionary slogans from the walls and demanded that electricity bills from the past five years to the present be paid.

After the regime terminated al-Manfoush’s contract on January 15, it immediately imposed additional taxes on goods entering the city. Commercial trucks, which can only enter though the Qaws al-Madina checkpoint, are taxed anywhere between SP3,000 ($14) and SP10,000 ($47) upon entering the city.

[Editor’s Note: Abu Ayman al-Manfoush, a trader appointed by the regime in August to control the flow of goods into the city, charged SP100 ($.50) on each kilogram of food, medicine, or any other good entering al-Tal. He continued to impose this tax — most of which he presumably pocketed, until January 15 — when regime officials removed him from the checkpoint and took over the monopoly.]

What role did a-Tal’s own reconciliation committee, which negotiated with the regime, play in the truce?

Part of the reason the regime isn’t holding up its side of the truce is that the reconciliation committee didn’t make the necessary arrangements to ensure that all terms of the agreement would be met. Whether or not it was intentional, the committee aided the regime by encouraging residents to expel fighters from the city. If residents did this, according to the committee, the regime would bring security to the city. So residents agreed, even though they’re aware of the regime’s dishonesty. They agreed to this truce because they were afraid of shelling and death.

Since it took control, the regime has held up the Syrian Arab Red Crescent’s delivery to the city more than once. The government doesn’t care about the agreement or its stipulations. The way I see it, this most recent delivery on January 12 is an anesthetic, it’s a way to keep people silent about the regime’s violations.

People thought that once rebels left, they would be able to live a pleasant life. They were patient once regime officials returned to the city, but they haven’t benefited at all from the agreement.

The Martyrs’ Father

Faraj Abu Ahmed, 52, is an al-Tal resident. His two sons, who fought with the FSA, were killed fighting the regime. He has two university-aged daughters.

I stayed in al-Tal so my daughters could continue their studies. Also, I don’t believe that leaving al-Tal will aid the revolution. Leaving my city and my home would signal the end of the revolution. I carefully considered the consequences of my decision and the possible harassment and trouble I could face from the regime. Even so, I decided to stay.

The disgrace that we’re experiencing now existed in all of Syria before the revolution. But no one spoke about it because the government’s security apparatus controlled us.

I don’t think that peace is possible in Syria if Assad stays in power. There is no peace with Assad as president. Everyone who lost sons and daughters to this revolution will never view Assad as anything but a criminal.

The words “freedom” and “revolution” have vanished from our vocabulary. We live in secrecy once again, since the walls have ears.

The revolution is an idea, one that won’t die. But we need more time to achieve it.

We’re upholding the revolution by staying here in al-Tal and remaining steadfast. Eventually, injustice will be defeated.

I never expected something in return for surrendering. I knew what would happen once the state entered the city. We’ve seen it happen in other cities, so we’re familiar with the regime’s false promises.

The fighters who left al-Tal didn’t surrender. We, residents of al-Tal, ordered them to leave. Those of us who stayed will do whatever we can to tell people what is really happening inside the city. We want our experience to be a lesson for residents in other rebel towns on how the regime is dishonest and deceitful. Even if you forget, this regime will always remember how you defied it.

We still discuss the revolution, but behind closed doors, like we did at the start of the revolution. If we spoke about these issues openly, we’d be arrested because there are a handful of regime agents inside of the city.

People in my neighborhood feel intense regret. The regime has not been loyal to its word. This reconciliation is fake and void. But our regret can’t help us now. We already surrendered to the regime.

The Opposition Activist

Umm Ashraf, 30, is an opposition activist from a-Tal who studied computer engineering

The regime’s word can’t be trusted. I don’t think its possible to achieve peace in Syria through ceasefire agreements. Peace will only be obtained through a military solution that completely disposes of Assad, or by pressuring Russia to stop supporting him.

I surrendered so I could keep living in my city, on this land. And this is what I received, but it came with a price—constant fear and intense surveillance. I could be arrested at any moment. I feel hopeless, because I don’t have the freedom to do what I want.

Since the regime entered the city, I can no longer talk about the revolution, except with my families and trusted friends. Other than that, it’s dangerous to talk. But I can still express my opinion through social media by using a pseudonym.

I regret the truce. The regime hasn’t left our young men alone since the city returned to its control. More than 90% of the young men who stayed involuntarily joined the regime’s forces. This is without counting those who were arbitrarily arrested.

Right now, I’m looking for a way to leave the city, even though it’s a risky move.

Life here is no longer bearable, and leaving is better than staying here and joining the regime’s forces. Right now they’re recruiting men, but maybe one day they’ll have women join them and fight. Or they’ll arrest us in order to further humiliate us.

The regime wants the world to view it as a gentle lamb that embraces its citizens once they go back to living under its control. It’s keen on protecting its image, especially after the publication of several reports about the regime’s bad treatment of a-Tal residents after the agreement.

The Citizen Journalist

Omar al-Dimashqi, 25, is a citizen journalist in a-Tal

The regime intensified its attack on the city after it proposed a 48-hour ceasefire agreement with the rebels on November 23, during which negotiations would be made. The rebels could either agree to the ceasefire, or the regime would burn the city.

At that time, some of the rebel leaders rescinded the agreement. In response, the regime began bombing the city again with barrel bombs.

Residents of a-Tal organized huge demonstrations on Friday (November 26), demanding for a ceasefire, using the slogan “No to war.” They did this after the regime closed the only road to and from the city and forbade government employees from going to work.

Residents supported the departure of rebels from the city, since this area is densely populated. About a million people live here. One shell can kill a large number of people. Houses and schools are overflowing with displaced people.

“A War Would Be Genocide”

Abu Ahmed, 35, is a resident of a-Tal

We decided on a ceasefire to prevent bloodshed, and because the city wouldn’t survive if a few barrel bombs fell. We couldn’t enter into a full-blown war with the regime; it would be genocide. Assad’s forces would use all types of forbidden weapons against civilians.

Although most of us don’t want the regime to enter the city, we have to accept this agreement.