PHOTO: Abdulmalik al-Houthi, the leader of the Houthi movement which controls Yemen’s capital Sana’a

After we reported on Sunday about the Saudi bombing that killed more than 140 people at a funeral reception in Yemen’s capital Sana’a, a reader wrote me:

I understand that you provide context in the article, however I feel it’s more for people with a working knowledge of the region. Could I please ask that you explain to me why Yemen is in a civil war, who are the factions? Most importantly, why are Saudi Arabia and the US so heavily implicated in it?

Is it wrong to interpret this as a proxy war between Saudi Arabia and Iran?

The first question I’d always ask is what resources does Yemen have / what interests do other countries have in Yemen? Another conflict over power / influence and who wants influence over a region that has nothing to offer? Clearly Yemen has something the big powers want (I refuse to believe this is simply a Sunni / Shiite conflict) – is it the geopolitical positioning of the Red Sea? Any oil hanging round at all or not really?

I responded:

Always start from the ground up. Uprising in 2011 v. the long-time authoritarian rule of President Saleh.

Saleh finally formally gives up office in 2012 but doesn’t give up hope of power. Meanwhile, VP Hadi becomes President but struggles to get Government with national support (“National Dialogue”).

Houthis, who have long had their ambitions in north of country, strike in late 2014. Saleh allies with them.

Saudis back Hadi. Iran backs Houthis, because they are anti-Hadi/Saudi. Civil war escalates.

As for resources, Yemen is one of poorest countries in world but it does have oil distribution networks — some of which have been controlled by Al Qa’eda in the Arabian Peninsula — to the Gulf of Aden.

EA has reported on Yemen since the 2011 uprising. Unfortunately, however, we do not have the resources to offer coverage on a daily basis, as we do with Syria and Iran.

So here is a guide to the conflict to keep at hand. Although it is six months ago, I think it is still a valuable starting point.

Yemen in Crisis

Zachary Laub

Council on Foreign Relations

Yemen faces its biggest crisis in decades with the overthrow of its government by the Houthis, a Zaydi Shia movement, which prompted a Saudi-led counteroffensive. The fighting has had devastating humanitarian consequences, and while the Saudi-led coalition and pro-government forces have rolled back the Houthis, they are no closer to reinstating the internationally recognized government in the capital of Sana’a.

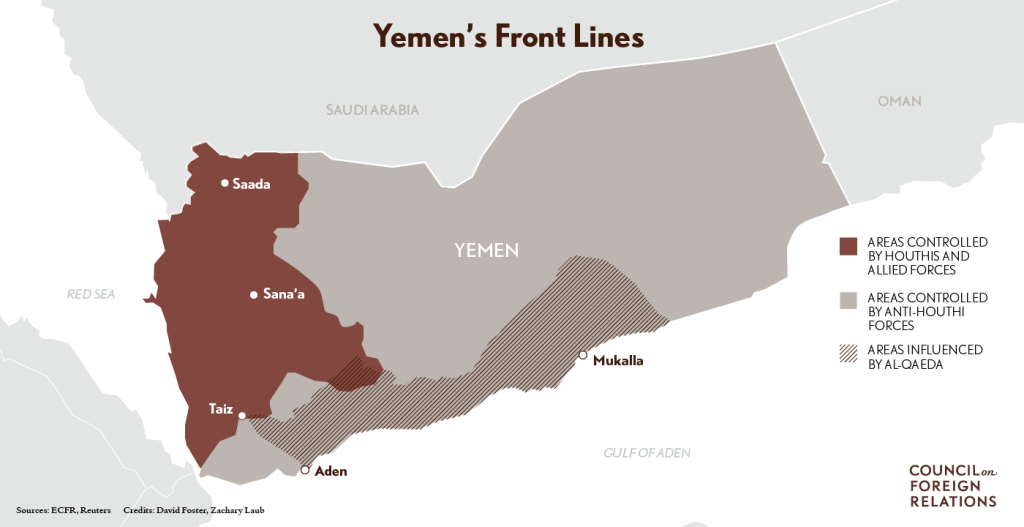

Amid factional fighting, al-Qaeda’s Arabian Peninsula franchise has captured expanses of coastal territory. Meanwhile, the United Nations has designated the humanitarian emergency in Yemen as severe and complex as those in Iraq, South Sudan, and Syria. The fighting, and a Saudi-imposed blockade meant to enforce an arms embargo, has brought the country to the brink of famine.

The Saudi intervention was spurred by perceived Iranian backing of the Houthis, and analysts worry that escalating foreign involvement could introduce sectarian conflict resembling fighting in Syria and Iraq. Numerous armed factions may be able to spoil any potential settlement, challenging UN-led efforts to broker a halt to the fighting. Even more difficult will be resolving the fundamental disputes over how power should be distributed in the Yemeni state, which had been the region’s poorest country even prior to the fighting.

Saudi troops in Yemen, August 2016

What are Yemen’s Divisions?

The modern Yemeni state was formed in 1990 with the unification of the U.S.- and Saudi-backed Yemeni Arab Republic, in the north, and the USSR-backed People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen, to the south. The military officer Ali Abdullah Saleh, who had ruled North Yemen since 1978, assumed leadership of the new country. Somewhat larger than the state of California, Yemen has a population of about twenty-five million.

Despite unification, the central government’s writ beyond the capital of Sana’a was never absolute, and Saleh secured his power through patronage and by playing various factions off one another.

Still, Yemen faced numerous challenges to its unity. Al-Hirak, a movement of southern Yemenis who felt marginalized under the post-unification government, rebelled in 1994; it has since pressed for greater autonomy within Yemen, if not secession. Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) and the related Ansar al-Sharia insurgent group have captured territory in the south. The Houthi movement, whose base is among the Zaydi Shias of northern Yemen, rose up against Saleh’s government six times between 2004 and 2010.

Washington lent its support to Saleh beginning in the early 2000s, when counterterrorism cooperation became Washington’s overriding regional concern. The United States gave Yemen $1.2 billion in military and police aid between 2000, when the USS Cole bombing in the Yemeni port of Aden made al-Qaeda a U.S. priority, and 2011, according to the online database Security Assistance Monitor.

Rights groups long charged that Saleh ran a corrupt and autocratic government. As the popular protests of the 2011 Arab uprisings spread to Yemen, the president’s political and military rivals jockeyed to oust him. While Yemeni security forces focused on putting down protests in urban areas, al-Qaeda made gains in outlying regions.

Under escalating domestic and international pressure (PDF), Saleh stepped aside after receiving assurances of immunity from prosecution. His vice president, Abed Rabbo Mansour al-Hadi, assumed office as interim president in a transition brokered by the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) and backed by the United States. As part of the GCC’s timetable for a transition, in 2013 the UN-sponsored National Dialogue Conference (NDC) convened 565 delegates to formulate a new constitution agreeable to Yemen’s many factions. But the NDC ended after delegates couldn’t resolve disputes over the distribution of power.

What are the Causes of the Crisis?

Fuel subsidy backlash: Under pressure from the International Monetary Fund, Hadi’s government lifted fuel subsidies in July 2014. The Houthi movement, which had attracted support beyond its base with its criticisms of the UN transition process, organized mass protests demanding lower fuel prices and a new government. Hadi’s supporters and the Muslim Brotherhood–affiliated party, al-Islah, held counter rallies.

Houthis seize power: The Houthis captured much of Sana’a by mid-September 2014. Reneging on a UN peace deal brokered that month, they consolidated control of the capital and continued their southward advance. Hadi’s government resigned under pressure the following January, and the Houthis declared a constitutional fiat.

Armed forces split: Military units loyal to Saleh aligned themselves with the Houthis, contributing to their battlefield success. Other militias mobilized against the Houthi-Saleh forces, aligning with elements of the military that remained loyal to the government. Southern separatists ramped up their calls for secession.

Saudis launch military intervention: After the Houthi reached Aden, Hadi went into exile in Saudi Arabia, which launched a military campaign, primarily fought from the air, to roll back the Houthis and restore the Hadi administration to Sana’a.

Who Are the Parties in the Conflict?

The Houthis began in the late 1980s as a religious and cultural revivalist movement among practitioners of Zaydi Shi’ism in northern Yemen. The Zaydis are a minority in the majority-Sunni Muslim country, but predominant in the northern highlands along the Saudi border, and until 1962, Zaydi imams ruled much of the region. The Houthis became politically active after 2003, opposing Saleh for backing the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq. The Houthis repeatedly fought the Saleh regime—and, in 2009, an intervening Saudi force. In post-Saleh Yemen, the movement gained support from far beyond its northern base for its criticisms of the UN-backed transition. However, in its push to monopolize power, it has alienated one-time supporters, writes the International Crisis Group.

Former President Ali Abdullah Saleh, though deposed in 2011 amid popular protests and elite jockeying, has gained in popularity among some Yemenis who have grown disillusioned with the transition. He and his son Ahmed Abdullah Saleh command the loyalty of some elements of Yemen’s security forces, tribal networks, and the General Peoples’ Congress (GPC) political party. Their alliance with the Houthis is a tactical one: Saleh’s loyalists oppose Hadi’s government, feel they were marginalized in the transition process, and seek to regain a leading role in Yemen.

Iran is the Houthis’ primary international backer and has reportedly provided the Houthis with military support, including arms. Yemen’s government has also accused Hezbollah, Iran’s Lebanese ally, of aiding the Houthis. Saudi Arabia’s perception that the Houthis are primarily an Iranian proxy rather than an indigenous movement has driven Riyadh’s military intervention. But many regional specialists caution against overstating Tehran’s influence over the movement. (Iranians and Houthis adhere to different schools of Shia Islam.) The Houthis and Iran share similar geopolitical interests: Iran seeks to challenge Saudi and U.S. dominance of the region, and the Houthis are the primary opposition to Hadi’s Saudi- and U.S.-backed government in Sana’a.

President Abed Rabbo Mansour al-Hadi, the internationally recognized president, returned to Yemen after eight months of exile in Saudi Arabia in November 2015, but he remains confined to the presidential palace in Aden and it is unclear whether he commands much authority beyond there.

Saudi Arabia has led the coalition air campaign to roll back the Houthis and reinstate Hadi’s government. Riyadh perceives that Houthi control of Yemen would mean a hostile neighbor that threatens its southern border. It also considers Yemen a front in its contest with Iran for regional dominance, and losing Sana’a would only add to what it perceives as an ascendant Iran that has allies in power in Baghdad, Beirut, and Damascus. Riyadh’s concerns have been compounded by its perception that the United States is retrenching from the region and that its nuclear accord with Iran will embolden Tehran. Journalist Peter Salisbury writes that Saudi Arabia may be trying to restore its long-standing strategy of “containment and maintenance” vis-à-vis its southern neighbor: Keep Yemen weak, and therefore beholden to Riyadh, but not so weak that state collapse could threaten it with an influx of migrants. The conflict is the first major one undertaken by the new king, Salman, and a test for his son, Defense Minister Mohammad bin Salman, who is pursuing a more adventurist foreign policy than his predecessors.

Saudi Arabia has cobbled together a coalition of Sunni-majority Arab states: Bahrain, Egypt, Jordan, Kuwait, Morocco, Qatar, Sudan, and the UAE. (That includes all the Gulf Cooperation Council states except for Oman.) The operation seems to consolidate Saudi Arabia’s leadership over the bloc, which has split over other regional issues, and signals consensus against allowing Iran to gain influence in Yemen. But in practice, only the UAE has played a significant military role, including contributing ground troops that enabled Hadi’s return to Aden.

The United States has backed the Saudi-led coalition, albeit reluctantly, along with the United Kingdom and France. U.S. interests include maintaining stability in Yemen and security for Saudi borders; free passage in the Bab al-Mandeb, the chokepoint between the Arabian and Red Seas through which 4.7 million barrels of oil per day transit; and a government in Sana’a that will cooperate with U.S. counterterrorism programs (PDF). In the current conflict, Washington has provided the Saudi-led coalition with logistical and intelligence support. It is also the largest provider of arms to Saudi Arabia, and in November 2015 approved a $1.3 billion sale to restock depleted munitions. But while the United States continues to support coalition operations, U.S. officials have pressed the Saudis for restraint, warning that the intensity of the bombing campaign was undercutting shared political goals.

What is the Role of Al Qa’eda in the Arabian Peninsula?

AQAP, described by the U.S. government as the most dangerous al-Qaeda affiliate (PDF), has benefitted from the current chaos, establishing what Reuters calls a “mini-state” that spans more than 350 miles of coastline and draws profits from the national oil company and port trade. The Houthis’ rapid advances have led some Sunni tribes to align with al-Qaeda against a perceived common threat. A distracted Yemeni army has eased pressure against the militants, who have rapidly expanded, and in some cases, reportedly fought alongside al-Qaeda fighters.

In April 2015, AQAP captured the city of Mukalla, and released three hundred inmates, many believed to be AQAP members, from the city’s prison. Since then, the militant group has expanded its control westward to Aden and seized parts of the city. Though U.S. drone strikes continue, in March 2015 Washington withdrew special operations forces that were training and assisting Yemeni troops, and the Saudi air campaign has reportedly destroyed military installations belonging to U.S.-trained Yemeni counterterrorism units.

Al Qa’eda, which has been in Yemen since the early 1990s, competes with the upstart self-proclaimed Islamic State for recruits. The Islamic State marked its entrance in Yemen in March 2015 with suicide attacks on two Zaydi mosques in Sana’a, killing about 140 worshipers. Its militants have portrayed their campaign in Yemen in distinctly sectarian terms, decrying the Houthi campaign as a Safawi invasion—referencing Iran. Though they have since claimed other high-profile attacks, including the assassination of Aden’s governor, the group has not gained as large a following in Yemen as Al Qa’eda has, the Wall Street Journal reports: Al-Qa’eda is enmeshed in tribal networks, whereas the Islamic State is perceived as foreign. The Journal estimates the Islamic State’s ranks in Yemen in the hundreds, and al-Qaeda’s in the thousands.

What is the Humanitarian Situation?

With a poverty rate of more than 50%, Yemen was the Arab world’s poorest country before the Houthi offensive and Saudi-led air campaign. The conflict has pushed the country to the verge of famine.

The UN estimated in January 2016 that 2,800 civilians had been killed since the escalation in March—60 percent of them in air strikes (only the Saudi-led coalition has these capabilities). Civilians have been targeted by both sides, in violation of international humanitarian law, a UN panel of experts found. Among the violations the panel cited was Saudi Arabia’s declaration of the entire city of Saada as a “military target”; the city has seen some of the war’s worst devastation, including the destruction of a hospital run by the international relief organization Doctors Without Borders. Elsewhere, the coalition and resistance fighters have targeted hospitals and schools, the panel found. It noted that Houthi forces have committed war crimes, as well, including in their siege of the city of Taiz.

The International Organization for Migration reports that 2.4 million Yemenis are internally displaced (a far smaller number have emigrated). In all, the UN says, 21.2 million people—four out of five Yemenis—need some form of humanitarian assistance; among them, 7.4 million have severe food insecurity.

Yemen relies on imports for the vast majority of its food and fuel. International organizations and nongovernmental organizations have been hindered from delivering food and medicine by ongoing fighting as well as an air and sea blockade that Saudi Arabia established to enforce a UN arms embargo. Airstrikes and ground fighting have also destroyed critical infrastructure, further hampering the distribution of aid.

What are the Prospects for a Solution to the Crisis?

Conditions appear daunting for a negotiated settlement. The Houthis’ assertion of power and the Saudi-led air campaign have militarized the divisions between the parties.

The Houthis, who long felt marginalized from Yemeni politics, “think that if they even compromise, that will mean defeat and their eventual elimination,” journalist Adam Baron told PBS Frontline, while southerners believe that the Houthis pose a reciprocal threat to them. Saudi Arabia and Iran are likely to escalate their commitments to their local allies as they compete for influence in Yemen and the broader region. That could introduce a sectarian dimension to Yemen’s civil conflict, making the conflict even more toxic. Meanwhile, the Houthis have indiscriminately shelled Saudi border towns, raising pressure on Riyadh.

But the Saudi-led intervention passed its one-year anniversary with its main objective, returning the Hadi-led administration to Sana’a, as elusive as ever, and with the financial and humanitarian costs of the conflict mounting, the parties have signaled some flexibility. UN Special Envoy Ismail Ould Cheikh Ahmed announced in late March 2016 that the parties had agreed to a cessation of hostilities, following confidence-building prisoner swaps, to facilitate the start of negotiations in Kuwait. A pause in fighting could allow Yemeni forces to focus on pushing back al-Qaeda.

The underlying causes of this conflict, however, will prove difficult to resolve: Political factions are unlikely to find a mutually acceptable compromise on the distribution of power, and militias will be reluctant to give up their arms. Reconstruction will depend not just on peace but regional donors at a time when Gulf oil revenues are shrinking. “Yemen was not just already incredibly impoverished before the war began but also at the brink of financial insolvency,” Baron writes. “If the war were to end in the coming weeks or months the damage that Yemen has suffered will take years if not decades to bring Yemen to a point where it is merely ‘underdeveloped.’”