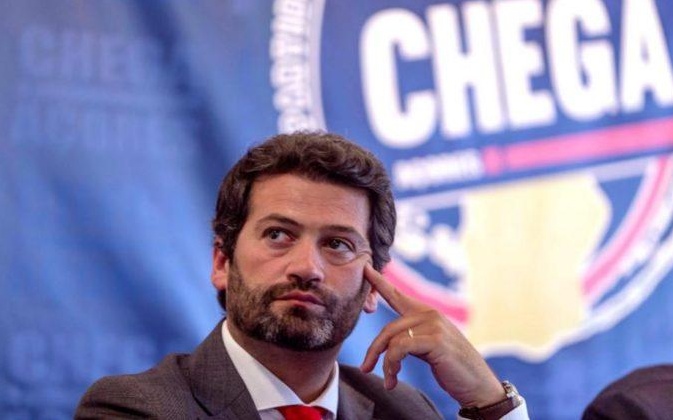

André Ventura, leader of Portugal’s radical right populist Chega Party

Portugal’s snap general election in late January drew international attention, thanks to the surprise outright majority of the incumbent left-of-center Socialist Party. It was a historic result for the PS, which had relied since 2015 on the support of two radical left parties to hold power.

At a time when many of the PS’s European counterparts struggle, it was little wonder that social democrats looked to Portugal for inspiration. But look beyond the surface of stability, and you’ll discover significant transformations in the Portuguese party system, particularly on the right.

Traditionally occupied by the center-right Social Democratic Party (PSD) — still the second largest party, and the Christian Democrat CDS-PP, the political right began to fragment in 2019 with the emergence of the populist radical-right Chega (Enough) and the Liberal Initiative (IL).

In 2022, Chega and IL rose from one seat each in the legislature to 12 and 8 MPs, respectively. In contrast, CDS-PP — a reliable coalition partner for the PSD — was left with no seats. With only a 28% vote share, the PSD made no advance on its 2019 performance and largely failed to meet expectations. In a more polarized party system, Chega and IL are adopting more radical positions than the now defunct CDS-PP — Chega on both cultural and socio-economic issues and IL on socio-economic matters.

Established in 2019 by the former PSD militant André Ventura, Chega is now the third-largest party in Parliament after leaping from 1.3% in that year’s vote to 7.2% in 2022. Chega’s leader had already performed strongly in the 2021 Presidential election, garnering 12% of the vote, and opinion polling has been relatively stable between 2020 and 2022, showing 5% to 9% backing.

See also Portugal’s Right-Wing Populism is A One-Man Show

Chega’s rapid growth is not just because of current circumstances. Researchers have identified a latent social “demand” for such a party, given the prevalence of populist attitudes among the Portuguese population. Indeed, these attitudes are so widespread that one may wonder why Chega’s standing is not higher.

Chega’s vote share is still below the average for radical-right parties in Western Europe. It has not yet benefited from the political opportunities that have aided many of its European counterparts, given the low salience of immigration as a concern amongst the Portuguese.

Ventura does better in municipalities with higher shares of Roma people, whom his rhetoric often targets. Still, Portugal seemingly remains “semi-detached” from this world, with specific socio-economic conditions and differences in the class and educational composition of its electorate.

But Chega’s rise clearly shows that there is a constituency for its claims, and its influence on the election’s results might be even more profound. Analysts have frequently noted that the concentration of the left-of-center vote in the Socialist Party, with an increase in turnout, were at least partially spurred by fear of a right-wing majority including Chega. Among the leaders of major parties, Ventura has the most negative evaluations in opinion polls: he scores 2.3 on a scale with 1 as very negative and 10 as very positive.

The leader of the center-right PSD, Rui Rio, said during the campaign that his party rejected an alliance with Chega, but his reassurances often seemed half-hearted or equivocal. At the same time, the PS was not receptive to his claimed willingness to negotiate. And there was a precedent for a PSD coalition with Chega: after the 2020 regional election in the Azores, the mainstream right consented to a series of demands by the populist party in exchange for its Parliamentary support. These included the reduction of “welfare dependency” (2subsidiodependência”), one of Ventura’s favourite policies.

Is Chega Here to Stay?

As elsewhere in Europe, the rise of the radical right in Portugal poses a challenge to the mainstream right as it spurs debate on potential alliances, including within the PSD. Much depends on the future leadership of the PSD.

But this is not just a matter for right-wing politics. Bringing together moderate parties in Portugal is complicated, not least because the country has no tradition of “grand coalitions” with a single exception in the 1980s. What Portugal does have is a tradition of minority governments, albeit mainly on the center-left.

The future inclusion or exclusion of Chega from Portuguese politics — and power — does not depend only on the mainstream right. It could also hinge on the future willingness of the center-left to accept governmence by a minority right-wing government that excludes the radical right.

For now, the center-left is firmly committed to a strategy of ostracizing Chega. It excluded the populists from talks with other parties and defended rejecton of the party’s candidate for Vice President of the Parliament. This has sparked much discussion, with both principled and strategic arguments, as to whether a cordon sanitaire approach is the best one.An adversarial strategy might be unwise if the goal is to prevent the growth of the radical right: given it attention might increase the salience of its preferred issues. At the same time, the confrontation might weaken the centre-left’s competitor, the centre-right.

If the PS is inclined towards a principled rejection of Chega and its ideas, it should consider that this does not necessarily require a permanent adversarial posture. Indeed, a dismissive strategy may be more effective, not least in a scenario where many of Chega’s “core issues” seem of little importance to the average Portuguese citizen.