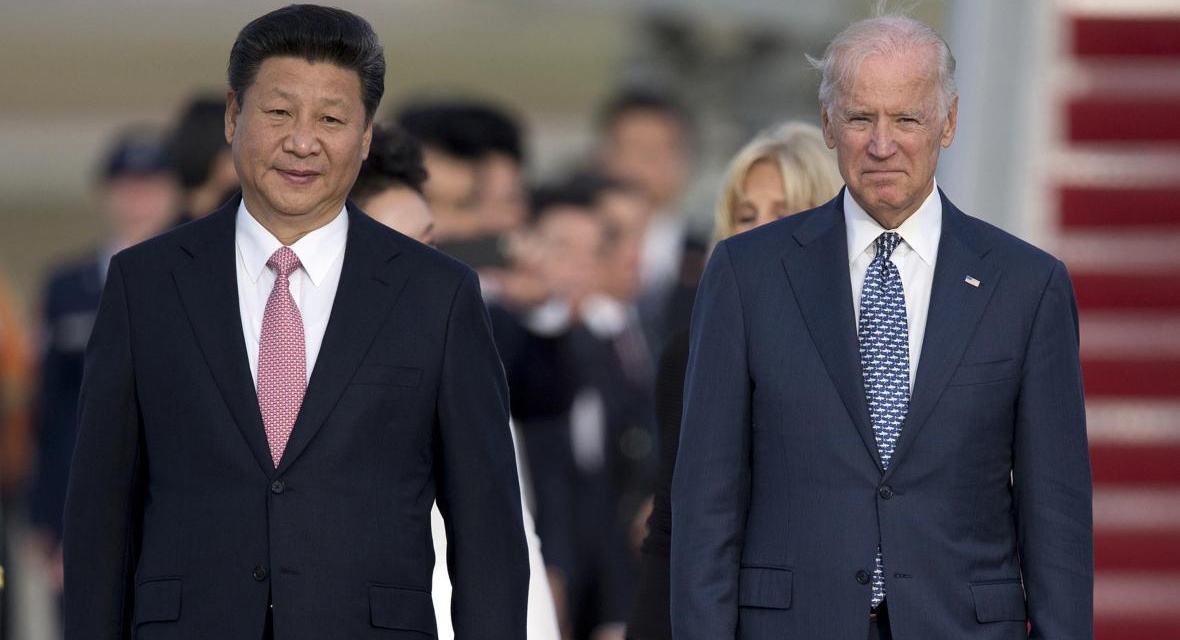

Joe Biden, then Vice President, with China’s leader Xi Jinping in 2015 (Carolyn Kaster/AP)

Addressing State Department staff on February 4, President Joe Biden announced that the US will return to its traditional global leadership from “a position of strength by building back better at home, working with our allies and partners, renewing our role in international institutions, and reclaiming our credibility and moral authority”.

But Washington is not the only power seeking the primary role. Biden noted “the growing ambitions of China to rival the United States”.

[We will] take on directly the challenges posed by our prosperity, security, and democratic values by our most serious competitor, China.

We’ll confront China’s economic abuses; counter its aggressive, coercive action; to push back on China’s attack on human rights, intellectual property, and global governance.

How exactly will the Biden Administration navigate the divergent interests of key regional allies when it comes to competing and/or cooperating with Beijing?

Constrained By “Competition”

The Trump Presidency, despite the vituperative tumult and inconsistency of its leader, set out the doctrine of great power competition with Russia and China, most emphatically the latter. The 2017 National Security Strategy labelled both as strategic competitors, intent on eroding the US-led liberal international order and shaping a world safe for authoritarian regimes. The Pentagon’s 2018 National Defense Strategy focused on increasing Chinese military modernization and capabilities as a threat to US security interests and America’s position of predominance.

Riding this reorientation of US strategy, the national security establishment, the think tank community, and the media all sprang into action. News articles using the terminology “great power competition” jumped from a meager 141 during the two terms of the George W. Bush presidency, to a whopping 6,500 in the first 2 1/2 years of Trump’s tenure. Trump’s former National Security Advisor and retired general H.R. McMaster led the charge with the drafting of the National Security Strategy, but the concept was embraced by most foreign policy officials and experts within the Beltway, broad sectors of the American economic community, and, most strikingly, Congress. As Professor Robert Sutter notes, “The Trump Government leaves a legacy of strong American countermeasures against Chinese challenges that will be hard to reverse, especially because the US Congress continues bipartisan support for such measures.”

The bipartisan consensus is manifest in the flurry of legislation on China which has circulated in the halls of Congress in recent years. No less than 366 bills were introduced since January 2019. The vast majority of these proposals have either stalled or been wrapped into larger pieces of legislation, such as the 2021 National Defense Authorization Act, with just 12 being signed into law. But the takeaway is the scale of Congressional activity focused on countering China. Republican Representatives set up a China Task Force in May, sponsoring legislation on issues such as the blocking Chinese 5G companies, such as Huawei, from access to US financial markets; establishing an Indo-Pacific Security Initiative; and contesting human rights abuses against the Uyghur population in northwest China.

Enter Biden

The new Administration is likely to take a dual track approach: competing with China over American security interests, globally and specifically in the Indo-Pacific, but cooperating on broader transnational issues such as the pandemic and climate change.

The main instrument in the strategic competition will be a renewed focus on multilateral diplomacy with allies to create a unified coalition. The Biden campaign argued that the world’s democracies should use their combined economic power to shape rules on trade policy, in stark contrast to Trump’s unilateral approach in his Trade Wars affecting not only China but also crucial allies. Biden said effective competition means constructing “a united front of friends and partners to challenge China’s abusive behavior”.

However, Biden’s foreign policy experience and history of engagement with China, as well as the composition of his national security team, means that there will not be an exclusive focus on confrontation. As Sutter notes, most advisors, like Biden, “have a recent history of nuance in dealing with China and notably do not express the sense of urgency about countering Chinese practices that has prevailed in Trump administration-congressional discourse about the danger posed by China over the past three years.”

The Administration will not promote the confrontational zero-sum mentality of its predecessor on transnational issues of common interest with China, but the Trump legacy, combined with widespread animosity within every major sector of American society towards China, will limit Biden’s range of action and prevent a return to the broad cooperative stance of the Obama years. As White House spokeswoman Jen Psaki made clear:

What we’ve seen over the last few years is that China is growing more authoritarian at home and more assertive abroad. And Beijing is now challenging our security, prosperity, and values in significant ways that require a new US approach.

Multilateralism is more of a correction of the Trump approach than a wholesale restructuring. In his first phone call with Japanese Prime Minister Suga Yoshihide, Biden reaffirmed the American commitment to the US-Japan defense alliance. He added a twist by including the Senkaku Islands (Diaoyu in Chinese), administered by Japan but claimed by China.

There is also significance in the attendance at Biden’s inauguration ceremony of Taiwan’s de facto Ambassador to the US, Bi-khim Hsiao, the first time since 1979 that a Taiwanese official was present at a high-level event. The signal came in the wake of the Trump Administration’s unprecedented lifting on January 9 of all self-imposed restrictions on US-Taiwanese official contacts.

Maneuvering in the Region

The Biden distinction, in contrast with the Trump era, is the connection of the China challenge to the broader goal of upholding a regional and international order underpinned by American leadership. Indicative of this shift is Biden’s appointment of longtime Asia veteran Kurt Campbell as coordinator for Indo-Pacific affairs on the National Security Council. Campbell was one of the driving forces behind the “pivot to Asia” strategy initiated during the Obama years, intended to reorient American strategy towards the Indo-Pacific across all dimensions of power.

In a January 12 article in Foreign Affairs, “How America Can Shore Up Asian Order”, Campbell outlined three core pillars of American strategy in the region: “the need for a balance of power; the need for an order that the region’s states recognize as legitimate; and the need for an allied and partner coalition to address China’s challenge to both”. In a prominent step away from the more conciliatory language of the Obama Administration, Beijing is positioned, as the primary challenge, not only in material terms, but also to the norms-based pillar of the regional order,

With Biden’s room of maneuver constrained by the Congressional and domestic consensus, the road forward will also be nuanced when it comes to navigating relations with foreign capitals. Strengthened engagement with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations and its constituent members could provide a bulwark against Chinese influence, but the sentiment in most of the region’s capitals is to chart a middle ground to avoid becoming a chessboard in the great power competition.

Japan is probably America’s most unambiguous regional ally, having adopted military modernization with a view to China and followed in the footsteps of Washington in banning Huawei and ZTE from official contracts in the 5G network. On the other hand, South Korean President Moon Jae-In has followed a policy of conscious ambiguity, avoiding both antagonism in the economic relationship with China and alienation of the US as Seoul’s primary security partner. Australia has been more forthright in viewing China as a strategic competitor in the security realm, but the country is constrained in the economic sphere where Beijing is its largest trading partner.

The Biden administration will have to juggle what Asia scholar Evan Feigenbaum calls the “two Asias“, one centered on geopolitical and security issues, another on the economic fabric.

On the first front, the Administration will likely continue along the Trump Administration’s National Defense Strategy. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin testified to the Senate Armed Services Committee that while the intention is to update the NDS, “the document is absolutely on track for today’s challenges”.

In his Foreign Affairs article, the National Security Council’s Campbell suggests reshaping the US military away from reliance on expensive and vulnerable platformsm such as aircraft carriers, to “investing in long-range conventional cruise and ballistic missiles, unmanned carrier-based strike aircraft and underwater vehicles, guided-missile submarines, and high-speed strike weapons”. He suggests increasing efforts at providing regional allies with similar capabilities and dispersing the burden of countering China.

The new administration could solidify the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (the Quad) between the US, Australia, Japan, and India into a formal defense alliance, and strengthen the overall U.S. alliance network in Asia, centered on protecting democratic values and principles of sovereignty against Chinese encroachment. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan, speaking at the US Institute for Peace on January 29, said the US will need to impose substantial costs on China for its human rights abuses against the Uighurs of Xinjiang Province and for the anti-democracy crackdown in Hong Kong. Secretary of State Antony Blinken echoed the comments.

Blinken has sounded a positive note on the possibility of increased cooperation with India, defining the relationship as a “bipartisan success story”. At the conservative Hudson Institute in July 2020, he said India is “going to be a very high priority” and vital for “the future of the Indo-Pacific and the kind of order that we all want”.

Yet the Administration’s purported support for human rights vis-à-vis China, might pose a serious risk to solidifying the Quad, as the Indian Government of Narendra Modi has been criticized heavily for its own bleak record of abuses of minority groups and its increasingly anti-democratic and authoritarian tendencies. Sullivan has outlined the Administration’s first priority to “refurbish the fundamental foundations of our democracy”, countering Chinese criticism of the US as a dysfunctional model of government, but if the administration is to leverage a renewed commitment to the appeal of American democratic values and principles too overt an embrace of the Modi Government could undermine the position on democracy and human rights.

On the economic front, a sea change will not occur until the domestic challenges of the Coronavirus pandemic, economic revitalization, and unprecedented political polarization have been addressed. Biden has made clear that significant change in the economic policies over China will have to await a full review in consultation with US allies, likely seeking to streamline existing tariffs and sanctions to gain trade concessions from China.

The Administration could coordinate with Japan’s initiative for regional democratic development – the Free and Open Indo-Pacific strategy – which seeks to bolster democratic governance throughout the region as a bulwark against increasing Chinese influence. It could use Japan’s position as the primary source of Foreign Direct Investment into Southeast Asia to compete with China’s ambitious BRI infrastructure scheme.

Most analysts also anticipate a Biden interest in renegotiating US adherence to the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership trade deal (CPTPP), previously known as the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), from which Donald Trump withdrew in in early 2017. As Vice-President, Biden was highly supportive of the deal, which was originally envisioned as the economic pillar of the Obama administration’s “pivot to Asia”.

However, the original TPP faced widespread opposition in the US, and any entry would require substantial changes to the deal’s outline to pass through Congress. Meanwhile, China has put in place its Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership agreement for the world’s largest trading bloc.

“Foreign Policy is Domestic Policy”

The new administration is unequivocal in emphasizing the linkage between the state of American domestic vitality and success at meeting China on the international stage.

National Security Advisor Sullivan said at the US Institute for Peace, “Foreign policy is domestic policy and domestic policy is foreign policy….Right now, the most profound pressing national security challenge for the United States is getting our own house in order.”

Secretary of State Blinken, speaking to the US Global Leadership Coalition in November 2020, said the approach to China, both in competition and cooperation, would have to come from “a position of strength” with a rejuvenation of the US economy, political system, and its outward appeal.

And in his only reference beyond US borders in his Inaugural speech, Biden set the ambition that “our America secured liberty at home and stood once again as a beacon to the world”.

That linkage is necessary but it sets up not one but two challenges at an unprecedented time: both to get a handle on the pandemic and its economic consequences — and on issues from immigration to social justice — and to get a grip on the US position vis-à-vis Beijing.