Marine Le Pen, leader of the French far-right National Rally Party, and Brexit Party leader Nigel Farage (File)

Originally published by The UK in a Changing Europe and drawn from the article “Eager to leave? Populist radical right parties’ responses to the UK’s Brexit vote” in The British Journal of Politics and International Relations:

After the UK’s Brexit referendum in 2016, eurosceptics across Europe cheered. The most fervent saw the imminent departure of Britain as an example to be followed, while others considered the vote as a sign that the European Union was in need of fundamental reform. There were voices, also beyond eurosceptic circles, that spoke of a domino effect with other countries departing the EU.

But now that the UK has finally left, few countries seem to have been inspired by the British example. If anything, the trend across member states has been an increase in public support for EU membership.

The findings in our article suggest that early predictions of an imminent domino effect were always questionable. We focused on parties of the populist radical right (PRR), considered to be the most likely instigators of departure, yet even the most passionately eurosceptic politicians were reluctant to campaign for their countries’ exit from the EU.

Studying Populism and Euroscepticism

Parties of the PRR — characterized by anti-immigration positions, opposition to cultural change, and populist anti-establishment discourse — criticize the EU for a variety of reasons.

They lament the loss of national sovereignty which they associate with deeper European integration. They dislike the opening of borders, as well as the EU’s supposed undemocratic and elite-centered nature.

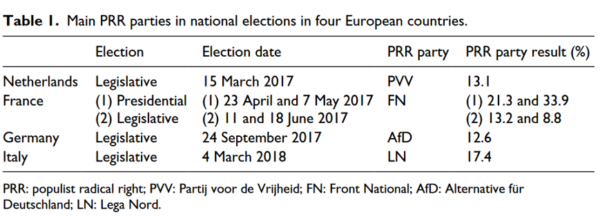

In our study, we focused on PRR parties in four founding EU member states: Partij voor de Vrijheid (PVV) in the Netherlands; Front National (FN; now re-named Rassemblement National) in France; Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) in Germany, and Lega Nord (LN; later known as Lega) in Italy.

We asked whether these parties were inspired by the Brexit vote in their national election campaigns, which in all cases took place within two years of the British referendum.

Did they draw attention to Brexit, and increase their general emphasis on the topic of European integration? Did they bolster their euroscepticism and demand a similar EU membership referendum in their own country, or even a unilateral withdrawal from the bloc?

Caution Rather than Demands for Exit

PRR parties initially reacted with some gusto to the Brexit vote. PVV leader Geert Wilders congratulated the British on their “Independence Day”, and argued that the Dutch deserved their own referendum. Italy’s LN declared that the British had “taught us a lesson in democracy”, whilE FN’s leader Marine Le Pen was similarly unequivocal in her praise for Brexit and her demand for a referendum in France. Alice Weidel of Germany’s AfD floated the idea of holding similar membership referendA across Europe.

Yet the Brexit vote failed to leave a more lasting mark on the strategies of PRR parties. European integration, in general, did not feature prominently in most of their election campaigns.

The case of Marine Le Pen, for whom “returning France’s sovereignty” was a key campaign pledge, was possibly the exception. Before the second round of the Presidential elections, however, she placed less emphasis on the EU, and her position — not least pertaining to the common currency — became more ambiguous.

The Dutch PVV already favored a “Nexit” well before the British referendum. In the 2017 Parliamentary election campaign, however, party leader Wilders preferred to prioritize his central theme of “Islamization”.

Apart from the PVV, the PRR parties ultimately shied away from advocating their countries’ unilateral withdrawal from the EU. Expressions of support for revoking membership or a referendum were voiced in a careful and non-committal manner: “ending EU membership may be necessary only if the EU fails to reform”.

The muted responses of PRR parties to Brexit can be explained in part by the relatively small appetite among European citizens for leaving the EU, but also by the comparatively low salience of the issue of European integration.

As long as PRR parties are successful by focusing on issues that are considered more important by their voters – not least those related to immigration and cultural change – their leaderships have little reason to take a risk and focus on themes that potentially divide their electorates or membershiips.

This is even the case in countries, like France and Italy, with considerable euroscepticism has reached considerable levels. As Duncan McDonnell and Anika Werner have argued, PRR parties “enjoy flexibility on European integration and can shift positions” precisely because of the issue’s limited salience among supporters and the public at large.

The uncertainty of the outcome of protracted Brexit negotiations, as a well as political instability in the UK, have further induced a cautious wait-and-see approach among PRR parties.

In the longer run, when there is clarity about the UK’s fate, there may well be renewed calls for leaving the EU. Yet this probably requires an increase in salience of EU-related issues and a concomitant rise in “exit scepticism” among European citizens.

The article “Eager to leave? Populist radical right parties’ responses to the UK’s Brexit vote” is in the latest issue of The British Journal of Politics and International Relations. It is co-authored by Stijn van Kessel, Nicola Chelotti, Helen Drake, Juan Roch, and Patricia Rodi. The research is part of the ESRC-funded project “28+ Perspectives on Brexit: a guide to the multi-stakeholder negotiations”, led by Prof. Helen Drake.