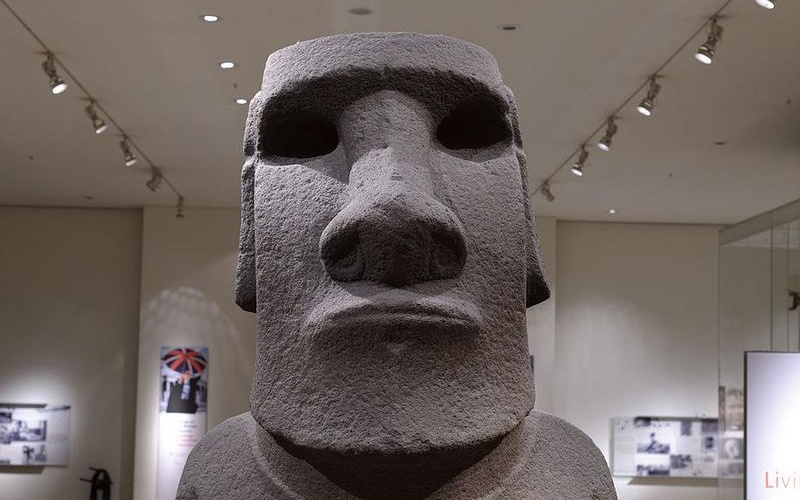

The Hoa Hakananai’a statue from Easter Island, held by the British Museum (Neil Hall/EPA)

Originally written for the Birmingham Brief:

The question of repatriation is on the table again for international negotiation. Discussion has moved on from previous decades. Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, and France have dedicated funds and focus to cases and envisioned guidelines. The staunch denial of the consequences of their extractive expeditions, colonial settlements, and neo-colonial endeavors has given way.

It is early days and there has not been much concrete transfer of property has happened, but many conversations are underway. Loans from giants like the British Museum (to New Zealand), Germany’s Humboldt Forum (to Namibia), and France’s Quai Branly (to Benin City) are underway. If the first repatriations that have been made — the Witbooi bible and whip from Stuttgart to Namibia, for example — have been ill-informed, they are instructive in their process.

What is a Proper Repatriation?

Repatriations cannot be made only on the terms and in the timeframes that suit European political whims. These often do not allow enough support to prepare the conditions for arrival in home countries. This has led to intensified horizontal violence between groups that were disrupted by their territory being carved up during colonialization. Their destabilization is a complex interweave of familial, tribal, and national governments and lobby interests that did not exist at the time of the looting.

This is why a considered approach based in ethical motives, research, and respect for the time and process needed at the receiving end is essential to the success of repatriations.

With legal questions looming large over seeming goodwill, a repatriation law is sorely lacking. A mixture of legal ideas drawing from transitional justice, human rights, heritage ,and intellectual property law are at play in different national systems. In the past, law, time, and convenient silence have been the means by which national museums have protected themselves from acting upon claims.

The value of these items makes it difficult for possessors to relinquish control over where and what they do. Considering whether the Global South can look after valuable material culture, the Ghanaian-Austrian legal advisor to the UN, Kwame Opoku, offered the analogy of a car being stolen — on being told to return it, the thief demanded to see the garage in which it would be parked.

Ancestral remains which are reclaimed are obviously far more significant than an expensive commodity. Reducing repatriations to finances is absurd in the eyes of those who do not keep art works as investments, but who live with them as family of a kind.

Museums like those in England remain with the long-term loan format. At best this ties both parties into a relationship, while avoiding a change of the law of inalienability which in the German legal system distinguishes between inalienable owner (Eigethumer) and exhibitor (Besitzer). A relationship maintains the responsibility of the European institutions to support the communities receiving these collections. Yet the gesture of a loan or gift does not make the same commitment as a transfer of ownership.

Immense gains in the process of repatriations come from open contact with a system of knowledge that goes beyond our own. Supporting knowledge through the circulation of their material vessels is the best outcome, for conservation was long used as a technical excuse to disguise a lack of political will.

It is telling that in the archives and collections of museums, non-western objects are not understood in their own terms. It is through repatriation that we gain respect for the value of that which we cannot know, interpret, explain, and own.