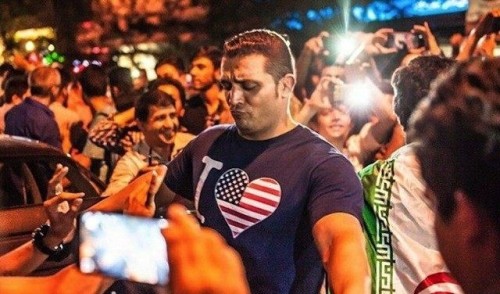

PHOTO: A distinctive image of America amid Tehran’s celebrations of Tuesday’s nuclear deal

Sadegh Zibakalam, professor of political science at the University of Tehran, is one of the leading political analysts in Iran. He is also one of the few commentators that can risk controversial statements — at least so far, as an 18-month prison sentence handed down in June 2014 has not been carried out — on topics from Iran’s position on Israel to the nuclear talks to the US-Iranian relationship.

This week Zibakalam spoke with Maysam Behravesh of the Tehran Bureau, in an interview published in the Guardian, about the significance of the nuclear deal and the prospects for Iran’s foreign policy and domestic politics.

How will the nuclear agreement affect the relationship between political groups inside Iran?

To be precise, the nuclear agreement will benefit the reformists, moderates and centrists. Historically speaking, during the life of the Islamic republic in particular, whenever our relations with the west were hostile and tense, pressures on the opposition, critics, dissidents, journalists and intellectuals sharply increased. On the other hand, whenever relations with the west shifted a bit towards détente, the situation improved a bit for the critics of the state.

I think such a dynamic will take place on this occasion too. A strong indication is that as much as the reformists and centrists supported the nuclear negotiations, the hardliners were harshly opposed and critical of the performance of the negotiating team. This was a telling prelude to what I said.

But taking lessons from the same historical experience you mentioned, the hardline and conservative groups may respond radically to the opening, so the circumstances may not improve as soon as expected.

Yes, there is the likelihood of such a reaction. And it is indeed far from a small possibility. It is possible that at the beginning, that is the day after the deal, conservative and radical forces will take action to show that the situation will not change in favor of opponents, critics, liberals and intellectuals. They may scale up certain penalties and restrictions here and there, like shutting down a couple of newspapers, summoning a few authors and journalists to the judiciary, or similar measures. These are likely to happen in the short run. However, I believe in the long term the political atmosphere in Iran will gradually open up as a result of the rapprochement with the west, and the US in particular.

What do you make of warnings that the nuclear deal is aimed at empowering pro-west forces in Iran and bringing changes to the state’s power structure?

It is clear that the hardline “principlists” are floating these issues to give the impression that there is a relationship between the nuclear accord and American plots to overthrow the regime. They are in fact trying to create such a psychological atmosphere. And I think these moves are driven by serious concerns about the deal, as hardliners know very well that it will not benefit them much in the long run. So these types of remarks, these “threats”, suggest a sense of worry and fear about the future.

If the nuclear deal causes the “flag of anti-Americanism (Amrikasetizi) to fall down” as you have famously put it, or according to you again, if it generates fundamental “cracks in the dome of anti-Americanism”, what will then happen to Iran’s foreign policy? Will the Islamic republic face an identity crisis in that domain?

Some may still beat the drums of anti-Americanism, but it will be difficult to persist with such policies and positions as intensely as before the deal. And this has a clear reason. Gradually, many Iranians will be asking the simple question that if we were able to resolve through intensive and persistent negotiations our differences with Americans on such a wide range of issue on the nuclear controversy — Fordow, Natanz, Arak heavy water reactor, number of centrifuges, termination of sanctions — why shouldn’t we be able to reach agreements with them on other issues?

Like on Afghanistan, where we not only lack real differences, but also enjoy strategic convergence of interests. Neither one of us wants the Taliban to restore power in Kabul. We don’t have differences in Iraq either, just common interests. Neither side wants Daesh — the Islamic State – to extend its dominance over Iraq. Neither side wants to see al-Qaeda and extremist groups dominate Iraq. Take Prime Minister Haidar al-Abadi’s government in Iraq, for instance. It is a moderate and relatively democratic one, which has invited Sunni groups to collaborate. His government enjoys a degree of national consent and consensus. Both Americans and Iranians support his administration.

Interestingly, I want to add that this shared interest also applies to Yemen. Neither one of us wants al-Qaeda to take over there. This is the case in Syria, too. Neither one of us wants al-Nusra Front or Daesh [the Islamic State] to take over Damascus. But I don’t want to talk in idealistic terms and rule out any sort of differences or divisions between us and the Americans. We do diverge over Israel. We do differ over the human rights issue, etc. There definitely are differences, but they more or less exist between all countries in the world. Do the US and the UK agree fully on everything? Or the US and France, the US and China, the US and Russia, do they concur on everything? Definitely not. But this cannot be reason enough for them to be enemies. Such logic also applies to the relationship between Iranians and Americans.

Therefore, I reiterate this widely recognized statement in Iran that “the dome of anti-Americanism has cracked”. Of course, the principlists will try to push the anti-Americanism agenda with greater force to show their supporters that this is not the case [that anti-Americanism is alive and well]. This is not sustainable in the long run, however. In my opinion, the existential philosophy of anti-Americanism has been undermined a bit. It has been brought under question. It has reached a dead end.

Don’t you think this break in our foreign policy pattern may create some sort of identity crisis at the state level?

No, I don’t see it in terms of a “crisis”, because what we have is the product of a historical process that is gradually taking shape in Iran. Just note that when the revolution happened in 1979, anti-western and anti-American sentiments were much stronger in the society. But now after 36 years many revolutionary leftists and radicals who used to be anti-American at the time, are no longer so. Most of today’s reformists were deeply radical in the first decade after the revolution, as they stormed the US embassy in Tehran, and took many Americans hostage. Yet, they gradually realized that it is much more important to have a free press, hold free elections, abide by the rule of law, than to adopt anti-American stances and say “death to America”, “death to England”, “death to the west” and “death to capitalism”. But not everybody changed as these early leftists did. Most principlists still adhere to anti-American and anti-western policies. But many in the country including students, writers, and journalists no longer believe in anti-Americanism.

How do you think the nuclear deal will affect Iran’s regional policy? Will it become more assertive and aggressive or moderate and restrained?

I am not sure about this to be frank, because ordinary people do not have a strong say in foreign policy making, particularly in places like Syria and Yemen. It is possible that once Iran feels powerful, it may adopt a more assertive position towards Saudi Arabia, but it is also possible that common sense prevails and the authorities extend an olive branch to the Saudis despite the fact our relations with the United States are entering a thaw. Tehran may invite Riyadh to engage in cooperation with the purpose of resolving the crisis in Yemen or in Iraq.

In other words, though Iranians may now be feeling stronger than before, common sense may incline them to extend a hand of friendship to Saudi Arabia. They can make friendly gestures like declaring that Ayatollah Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani or President Hassan Rouhani or Foreign Minister Javad Zarif would like to pay a visit to King Salman.