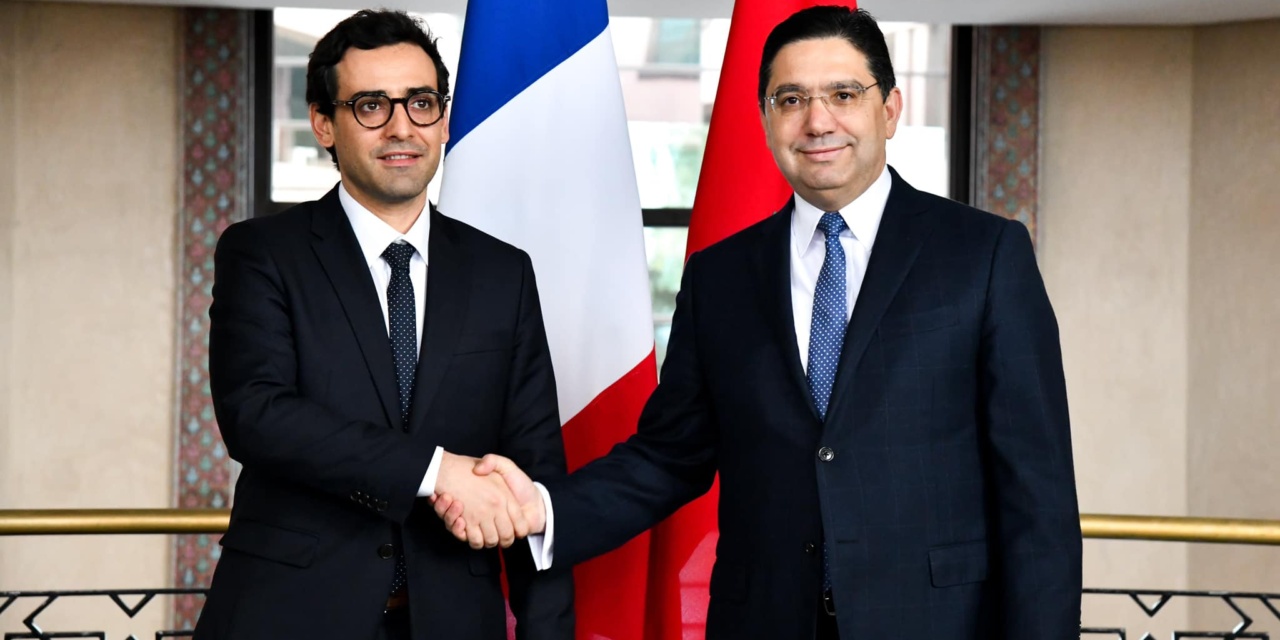

French Foreign Minister Stéphane Séjourné with Moroccan counterpart Nasser Bourita, Rebat, Morocco, February 26, 2024

Last September 8, an earthquake struck western Morocco, about 75 km (46 mi) southwest of Marrakesh. At least 2,960 people were killed and 5,500 people injured in the initial 6.8-magnitude tremor and the aftershocks.

Parts of ancient Marrakesh were heavily damaged, but the hardest-hit areas were rugged, hard-to-reach hillsides and valleys. Several remote settlements in the Atlas Mountains were devastated. With roads impassable because of boulders and other debris, rescue teams were slowed. Days after the earthquake, survivors needing tents, food, and water had yet to receive help.

Many governments offered assistance, but two days after the catastrophe, Moroccan authorities issued a communiqué in which they accepted the help of only four countries: Spain, the UK, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates.

Absent from the list was France, a notable omission given the history and the geographical position of the two countries.

From 1912 to 1956, Morocco was a French protectorate, a colony in all but name. After a relatively calm negotiation of independence, the two countries maintained cordial relations and cooperation. France is one of Morocco’s main commercial partners.

So why didn’t Morocco want the help of France when facing the deadliest earthquake in its history?

Moroccan authorities said their choices were based on technical and geographical criteria. The explanation raised eyebrows, given that Qatar and the UAE are not exactly neighbors or countries with a record of rescuing people from environmental catastrophes.

The real answer probably lay in the Western Sahara.

The Downward Spiral in Relations

Since the departure of the Spanish colonial power in 1975, control of the Western Sahara has been disputed between Morocco and the Algerian-backed Polisario Front.

The region is strategic, with a soil rich with iron, uranium, gold, petrol, and gas. It is also a sacred patriotic cause in Morocco. Hassan II, the father of the king, faced two attempted coups in 1971 and 1972. To regain legitimacy on the throne, he organized the “Green March” in October 1975, a demonstration that precipitated Spain’s departure from the Western Sahara. Morocco buttresses the claim with the assertion of “historical rights” conferred by ancient tribal allegiances.

The United Nations has deemed Western Sahara as a “non-self-governing territory” with a right to self-determination. But in 2020, the US’s Trump Administration recognized Moroccan sovereignty over the area in exchange for the normalization of diplomatic relations between Rabat and Israel. Emboldened by this decision, the Moroccan leadership raised the issue of recognition with other countries, including France.

Since the end of Spain’s presence in the region, the French position is clear. The country does not recognize Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara and aligns itself with the UN’s positions. As other European countries like Spain and the UK fell in line with the Trump Administration, the wait-and-see attitude of France exasperated the Moroccans and began to fuel diplomatic tensions between the two countries.

The Presidency of Emmanuel Macron has added fuel to the fire. Upon taking power in 2017, his first goal in the Maghreb region was to improve the relationship between France and Algeria.

Macron might have been trying to rectify a history of troubled relations, before and after Algerian independence in 1962 that followed eight years in war. But Morocco’s court and political elite saw Paris giving preference not only to a long-time antagonist of France but also to a country backing the Polisario Front against Morocco over Western Sahara.

In mid-July 2021, the Paris-based media outlet Forbidden Stories published the Pegasus Project. The investigation revealed that Moroccan authorities had used Israeli spyware to hack the phones of Macron, ministers, and other personalities, gaining access to their conversations.

In September 2021, the French administration responsed with visa restrictions on citizens of the Maghreb region, especially Moroccans. The restrictions were cancelled in December 2022, but the damage was done.

It was compounded by claims in 2022 that Morocco tried to corrupt members of the European Parliament. The allegations of Rabat trying to influence the legislators’ decisions — through donations of money, gifts, and travel — included the annexation of Western Sahara.

Some MEPs, notably French representatives affiliated to Macron’s party, proposed sanctions against Morocco. Consequently, Rabat did not replace its ambassador in Paris in January 2023.

The Way Back

But for all this tension, there is still a basis for cooperation. The cultural, economical, security, and societal links between the two countries are still vital.

France is still a center of immigration for Moroccans, who bolstered its labor force after the World War II. The French language retains a central place in Morocco, and many students and a large part of Morocco’s “elite class” are enrolled in French universities. Morocco is a base for French investments and the two countries are commercial partners of the first order. Moroccan and French intelligence services have remained partners over security and counter-terrorism matters.

So in October, the Moroccan Ambassador returned to Paris. After a year, the French Ambassador in Rabat was accredited.

And on February 26 — a week after a lunch between French First Lady Brigit te Macron and King Mohammed VI’s three sisters at the Elysée Palace — the new French Foreign Minister, Stéphane Séjourné, came to Morocco in his first visit to a Maghreb country.

Paris still has not recognized Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara. But the French language evolved in a statement by Séjourné during his visit:

France knows that the Sahara issue is existential for Morocco….

We’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again today, perhaps even more forcefully: It’s time to move forward. I shall see to it personally.

So will the intense lobbying by Morocco finally bring the fulfilment of its long-pursued goal? Or will France balk at the final step of recognizing Rabat’s primacy in the Western Sahara?

Very insightful article: It helps better understand the crucial context surrounding this humanitarian help controversy – Thank you!