Ukraine President Volodymyr Zelenskiy speaks to journalists in the town of Bucha, near Kyiv, April 04, 2022 (Metin Aktas/Anadolu)

On February 26, 2022, the third day of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Ihor Hudenko cycled with his camera on his shoulder to Kharkiv’s frontline, as Russian units were surrounding the northern and eastern outskirts of the city.

He never returned home.

Almost three months later, Hudenko’s colleague Oleg Peregon, told the Committee to Protect Journalists that the photojournalist died within hours of leaving his house. The circumstances and events surrounding the death are still unclear.

On March 1, camera operator Yevheni Sakun was one of five people killed by a Russian missile strike on Kyiv’s TV tower. This time the murders, if not Sakun specifically, received global attention. In a small park across a narrow street from the tower, the Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial, commemorating the 33,771 Jews assassinated in 1941 by German SS officers and local collaborators, was damaged.

Just back from the site of last night’s Russian strike, the target was definitely the building directly next to the TV tower. There is a narrow street between it and the small park the houses the Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial site. There was no ordinance found inside the site. pic.twitter.com/05jd761coe

— Oz Katerji (@OzKaterji) March 2, 2022

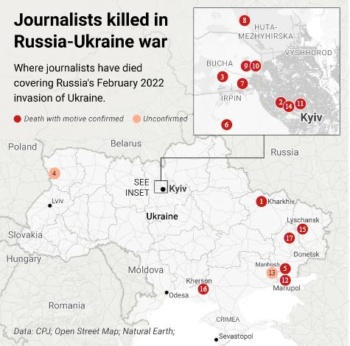

From those opening days of Russia’s war on Ukraine, the lesson was stark: no journalist, whether on a little-noticed frontline or in a high-profile site, was safe. By July 2023, 17 media personnel had been killed while covering the invasion, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists, with AFP reporter Arman Soldin and the Ukrainian Bohdan Bitik, a fixer for Italy’s La Republica, the latest victims.

See also Reporting Inhumanity and Humanity From Bosnia to Ukraine: The Story of Arman Soldin

It is crucial “to stress the importance of recognizing journalists as being civilians in this conflict”, emphasizes Lucy Westcott, the director of CPJ’s Emergencies Department — their killings are a war crime. And it is important to note that for those who have survived, the hazards are beyond the physical. The mental health of each of them is at stake.

“I don’t regret my choice but the decision has altered my life and mind forever,” says Fox News international correspondent Trey Yingst. The “lifeless bodies strewn across the landscapes” will always be with him.

It is a universal hazard, affecting the frontline reporter and potentially the online investigators scrolling uncensored content: seeing the sights that one should never witness.

Lucy Westcott, director of the Emergencies Department of the Committee to Protect Journalists, tells EA WorldView of “enormous risks to the lives of journalists” — not just the physical risk but the psychological, from both the real and digital worlds.

In conflict reporting, “one’s mental health can be very seriously put at risk because of the types of things that you are seeing and hearing”, she summarizes.

The Damage From the Physical to the Mental

“I thought that my trauma wasn’t quite serious. But it was an illusion,” explains award-winning Ukrainian journalist Andriy Tsaplienko.

Map: Committee to Protect Journalists

In the opening phase of Russia’s invasion, several journalists were slain in a theatre of intense fights as Moscow tried and failed to vanquish the Ukrainian government and its people. But with the Russian withdrawal from northern Ukraine, the frontlines in the east and south — as well as the aftermath of occupations near Kyiv and Kharkiv — brought further horror of atrocities.

Journalists returned from the battlefield with PTSD, manifesting itself in flashbacks, nightmares, hyper-vigilance, or avoidance personality disorder. Fox’s Trey Yingst adds “survivor’s guilt or the loss of identity”.

Stuart Ramsay of Sky News lived, with a wound in his back, as four colleagues perished in an ambush by Russian saboteurs. He describes self-blame, after protective gear saved him by absorbing six bullets. “Civilian families have no chance, no chance. They are definitely going to die. That’s what was upsetting me,” he says.

In his book The Madness, BBC war correspondent Fergal Keane, who has reported from Ukraine since 2014, writes about his “daily bread” which is “the suffering of others”. He was “addicted to part of the experience” of war: from the adrenaline rushes in which he could forget “all the mess up” from home, to the feeling of camaraderie with colleagues creating an “alternative family”. Frontline reporting brought acclaim and awards — and, at the same time, the PTSD, nightmares, and panic attacks.

Journalists surrounding victims of atrocities in Bucha, a suburb of Kyiv occupied by Russian forces from March 4 to 31, 2022 (Marko Djurica/Reuters)

Beyond this, the 21st-century media environment threatens more damage. Reporters are attacked on social platforms, with their first-hand accounts buried by disinformation. “Reality” gives way to distortion, ad hominem targeting, and harassment.

Marianna Spring, the BBC’s first official correspondent covering disinformation, says matter-of-factly about the death threats and hyper-sexual slurs she faces, “It is not always easy to cope with.”

Some of the attacks come from a fringe of the information landscape who, in the guise of “independent journalism”, echo the lines of authoritarian states. Doing so, they undermine the legitimate pursuit of autonomous journalism and challenges to “imperialism”. The authoritarian states and their institutions in turn harness deception and disinformation to bury reporting that is perceived as a threat.

In her book Putin’s Trolls, Finnish journalist Jesikka Aro describes the individuals paid by digital factories, using fake profiles and multiple languages, to spread propaganda and attack reporters across social platforms.

After she published articles in 2014 about the disseminators of confusion, exposing operations that were meant to remain secret, Aro became a target. Her “social media and professional communication channels melted down”, as purported “journalists” spread lies about her — the “rotten herring” technique as she labels it, tarnishing her and her reputation with the stink of a decaying fish.

“They are building a bigger and bigger community who just hate us and feel that we are bad and toxic,” she explained to a conference of international fact-checkers.

Supporting Journalists’ Bodies and Minds

Founded in the US in 1981, the Committee to Protect Journalists is “an independent, non-profit organization that

promotes press freedom worldwide”. Beyond documenting casualties within the profession, and building on the safety required for a free press, it acts to stem the risks to journalists.

Mitigating dangers requires extensive and costly resources, such as first aid kits and personal protective equipment including helmets and bulletproof vests. As the 2402 Fund — named after the date of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — notes, many reporters and especially local correspondents “do not have access” to life-saving devices. Beyond funding, logistical assistance is provided by CPJ to move PPE across borders, “due to the variety of laws across the region”.

CPJ also has provided invaluable information, especially at the start of the invasion when the situation was “very, very fluid”. Later, as the fighting settled in the Ukrainian landscape, reports focused more on how to safely navigate an environment scarred by war. One task was to spread knowledge of the presence of explosive devices, especially in areas liberated from the Russian occupation.

The 2402 Fund has provided HEFAT (Hostile Environment and First Aid Training) for Ukrainian journalists, with the teaching of tactical medicine, evacuation procedures,“mine safety”, and skills in assessing the potential hazards of combat zones. The Fund has also established a checklist helping reporters “to consider and negotiate all possible security risks before a dangerous assignment”.

Fund 2402 held the last three-day HEFAT training in Kyiv this year for media workers working in war conditions.

Despite the difficult conditions and the lack of light, 40 Ukrainian journalists acquired skills in tactical medicine and evacuation of the wounded👇 pic.twitter.com/pZsHyk3SNy

— 2402 Fund (@2402fund) December 14, 2022

But what about the security of journalists’ mental health?

Hannah Storm founded the Headlines Network, a platform allowing reporters “to speak openly about their experience” and aiming to create “cultures of compassion, inclusion and empathy” within the profession. Co-directed with John Crowley, the initiative has helped reporters who covered war zones, including Ukraine, to engage in discussion.

The space is where Sky’s Stuart Ramsay admitted his survivor guilt after the Russian ambush targeting his team on February 2022. He recalled the first days after the experience were hard to process. When he heard “the audio…rather than [saw] the pictures”, he “broke down in tears immediately. All of us found it quite hard.”

Working with the Oxford Research Institute in Journalism, Storm has developed techniques for managing mental health while covering war stories, be it on the ground or “from afar”. She insists on the limitation of exposure while dealing “with the most upsetting material”.

In a conflict where Russian forces have circulated video of the beheadings of Ukrainian POWs, online investigator Eliot Higgins reminds journalists and the public in general: “Dealing with such imagery needs to be professionally justified and treated”.

Guidance is essential. CPJ emphasizes the need to identify the warning signs — unusual isolation, unwanted intrusion of images, or sleeping difficulties – before mental wounds become more serious.

Where it has not been possible to contain the damage, CPJ strives to ensure access to medical facilities and treatments, covering costs. The approach is case-by-case, with Westcott and her colleagues assessing and addressing the reporter’s needs.

“That’s for journalists everywhere. If you have faced psychological difficulty because of your reporting, we are able to provide a grand,” Westcott explains.

The Costs for Ukraine’s Journalists

In April 2022, Bel Trew, the Chief International Correspondent of London’s The Independent, explained how “so many Syrian friends” of her media colleagues are struggling with the psychological damage of reporting on the 12-year conflict within the country. She asked readers to support organizations involved in mental health assistance to reporters witnessing the violence unleashed on their lands.

Lucy Westcott notes that the “added layer of harm” is also suffered by Ukrainian media personnel: “They are themselves living through the war that they are reporting on.”

Foreign journalists who went to Ukraine sought to report from there. Many of them have experience in navigating the conflict zone.

For Ukrainian counterparts, it was less a question of choice – each of them was thrown into the immediate necessity of providing information about the Russian invasion. For example, Ihor Hudenko, the first journalist who perished in the war, was a reporter on environmental issues and green social movements around Kharkiv.

The danger is not just on the battlefield. Russia’s missile, drone, and artillery attacks reach into most Ukrainian cities, towns, and villages. A local correspondent explained to Lucy Westcott, “The most dangerous time for her as a Ukrainian journalist was not actually reporting from the frontline. It was just being in Kyiv and seeing a missile behind her when she was driving.”

Ukrainian firefighters respond to a Russian rocket attack on a residential building, Kyiv, Ukraine, February 24, 2022

Even a home is not safe. At the end of April 2022, as UN Secretary General António Guterres visited Kyiv, the Russians fired two missiles on the Shevchenkivskyi district. One of them struck a residential building, killing Vera Gyrych, a journalist and producer for Radio Liberty, as she sat tranquilly at home.

And Still They Persist

At the start of 2023, Westcott asked herself the question, “How had Ukrainian reporters lived through the hostilities?” She recalls, “That mental health theme came up again, and again, and again.”

But she saw that the journalists could not, as a layer of protection, distance themselves from the story. Their land, their cities, and their people are under attack. They had to report on sufferings even as, through that coverage, they would share part of that anguish.

“There is a desire to keep reporting on war costs. This is the most important story of their lifetime,” Westcott notes succinctly.

Illia Ponomarenko is a journalist at the Kyiv Independent. He was born in the Donbas, the region that Moscow has tried to control for nine years. He lives in Bucha, the town near Kyiv which has become a symbol of the mass killing of civilians by Russian troops.

Days after the discovery in April 2022 in Bucha of the bodies of hundreds of people slain by the Russians, many of them executed with their hands tied behind their backs, Ponomarenko wrote:

When this war is over, I’m gonna quit war journalism.

Fuck it.

I’m gonna get a quiet remote place to live and will be writing stories of whales and polar explorers.— Illia Ponomarenko 🇺🇦 (@IAPonomarenko) April 5, 2022

Asked what prompted the tweet, the journalist said he was spurred by “the picture of a four-year-old boy, Sasha, killed by the Russians”: “After that, I decided that I don’t want to do this anymore.”

But he added, “I am taking this [emotional] toll until this war is over.” Reporting was a service “not to the government, but to the nation, the people you meet every single day in the street”.

He reflected, “This anger fills us up, gives us the strength to work more, but it’s very exhausting.”

Thank you again for thèse reports that bringue us info intolérable what à journalist suoorts in à war,especially if it is about his country hé is thé journalist

Just à question::thé russians whe.n thé make vidéo reports are thé always bonus reports

Another one:i West to another site infodefe.nse which seems to me ratier

Suspicious:il shows abusés by ukrainiens on unarmed russian solaires

What do you think about this

War is not always White or black

Marty,

Thank you for this.

Yes, Ukrainian soldiers have abused Russian POWs. This has been reported by the UN and activists, and acknowledged by the Zelenskiy Government. We have written about this.

Two important points for context: 1) The vast majority of abuses of POWs and civilians have been by Russian forces; and 2) Kyiv has investigated the abuses, whereas the Kremlin has shown no intention of doing so.

S.

Je viens d’écouter un reportage sur la résistance en Birmanie:un reportage exceptionnel que je vous recommande

Votre article s ‘inscrit dans ce qui fait la qualité de ce reportage

Pour le comprendre ,il vous suffit de le consulter sur France culturek

There is in this report everything that des thé réal job of thé journalist:getting in touche thèse Who are on thé front line:à double succession

Cheer@

à very detailed article on thé underside of thé cardinal for the risks and thé impacts on journalists and their rôle in extraction information on this conflict

Thanks

Very important article. It is easy to forget that behind the news about cruelty, those reporting are witnessing and being exposed to it.