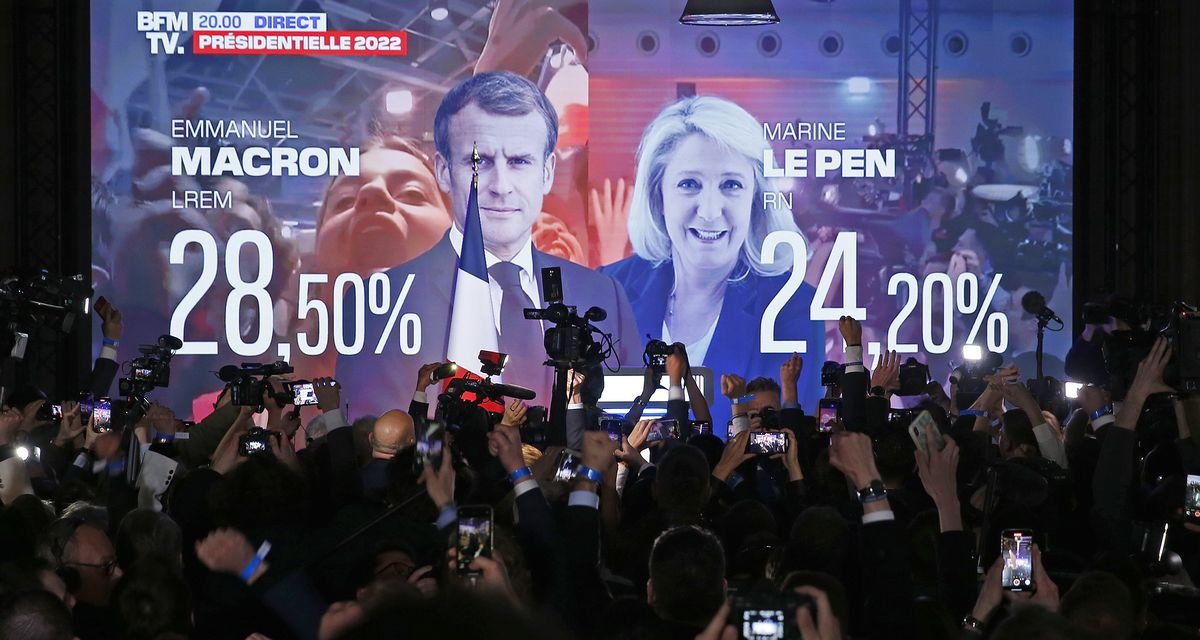

Photo: Chesnot/Getty

On April 24, incumbent Emmanuel Macron and radical-right contender Marine Le Pen will face off in the second round of the French Presidential election.

The two candidates received 27.84% and 23.15% respectively in Sunday’s first round. Le Pen was narrowly ahead of left-wing challenger Jean-Luc Mélenchon, who, after a late surge in the polls, received 21.95%. Far behind were radical-right journalist turned politician Eric Zemmour (7.07%), leader of the mainstream center-right Les Republicans Valerie Pécresse (4.78%), and Green leader Yannick Jadot (4.63%).

The Campaign and the First-Round Results

Fulfilling most predictions, the second round will be a re-run of the 2017 election in which Macron won power. Both candidates improved their scores of 2017, Macron by nearly 4% and Le Pen by about 2%.

Le Pen’s rise is testament to the success of her strategy of normalization. Taking over the Front National in 2011, she has spent several year presenting the party as more acceptable. Without substantively changing the nature of the party’s policies, she backtracked on some of its more controversial stances. She expelled militants holding exceedingly radical views — including her own father and founder of the Front, Jean-Marie Le Pen — and changed the party’s name to Rassemblement National.

In the 2022 election, Le Pen’s task of normalization was assisted by the entry of Eric Zemmour. His extreme positions on Islam, immigration, and women placed him on the right of Le Pen and bore a striking resemblance to the language of the pre-2011 Front National. In comparison, Le Pen appeared moderate.

Le Pen also ran a better campaign than in 2017. Instead of focusing on big rallies, she played to her strengths and spoke at small, local meetings. This “proximity” campaign strategy put her closer, at least in appearance, to the concerns of the French public. In stark contrast, Macron barely campaigned.

Early on, Le Pen decided to base her campaign on economic issues rather than on the identity and immigration issues for which her party is best known. Leaving behind her core issues was a gamble, but it was a smart move after the COVID-19 pandemic, and proved to be a lucky one amid the war in Ukraine. The RN’s younger and working-class electorate has been hard hit by Coronavirus and by the economic consequences of the sanctions on Russia, so a focus on increasing their purchasing power had appeal.

Unlike Le Pen, who announced her candidacy in 2020, Macron declared his very late in the race, only confirming it on March 3 this year. He had little time to present his programme. More importantly, some of the measures he announced, such as raising the pension age, proved to be widely unpopular. He also refused to debate other candidates, arguing that previous presidents had not done so.

However, Macron also benefitted from a rally-around-the-flag effect following the beginning of war in Ukraine. Already highlighting France’s rotating Presidency of the European Union, he sought diplomatic solutions to the conflict with the aura of a man who could defend France’s interests on the international stage.

Meanwhile, in the “tripolarisation” of the French political space — a split of voters between the radical-right Le Pen, centrist-liberal Macron, and the left-wing Mélenchon — the election featured the demise of the traditional parties that dominated French politics until 2017.

In 2007, the Parti Socialiste and Les Republicans shared 57.1% of the vote. In 2022, they could not even garner 7% between them. For the Parti Socialiste, this was the sequel to Macron’s 2017 campaign in which his sudden arrival sought to “explode” the socialists and win over its voters and cadres. On Sunday, the PS’s Anne Hidalgo was left with only 1.74% of the vote, the worst-ever outcome in party history.

Having exploded the Socialist Party, Macron spent the last five years trying to detonate Les Républicains. Squeezed between Le Pen and Zemmour on one side and the President on the other, riven by indecision over whether they should propose more moderate policies or more radical ones, and marred by a poor campaign, Les Républicains not only lost to Macron but sank far below Le Pen and even below Zemmour.

Adding economic pain to political injury, both the Parti Socialiste and Les Républicains failed to reach the 5% threshold guaranteeing the reimbursement of campaign fees. Now they struggle to stay afloat financially.

To the Second Round

Over the next two weeks, the task for Le Pen and Macron will be to win over voters who chose a different candidate in the first round.

For Macron, this will likely be the beginning of a proper campaign. While he led the first round, and several former candidates have announced they will be voting for him, Le Pen is still close — and Macron does not have a huge reservoir of votes available from those knocked out yesterday.

The President will have to convince voters of the strength of his program and vision for France over the next five years. He is also likely to present his opponent as unreliable and dangerous, stressing her ties with Russian leader Vladimir Putin. Macron will probably repeat his 2017 presentation of himself as the only rampart left against extremism. However, this attempt at gathering republican forces around him may be less successful than in 2017: as he has not been able to diminish the electoral power of the extreme right, voters may be sceptical of his ability to do so now.

Le Pen will be keen to continue her “normalization” campaign. She can already count on the votes of many supporters of Eric Zemmour or Debout la France’s Nicolas Dupont-Aignan; however, she must establish reach beyond those groups. To attract new voters, she is likely to present herself as the candidate of change, and the only alternative to Macron’s grip on power.

For both Macron and Le Pen the key will be to attract voters from the third-place Mélenchon. Although the left-wing candidate explicitly told his voters not to cast a single vote to Le Pen, he stopped short of inviting them to vote for Macron. Early polls suggest that Mélenchon’s voters split more or less evenly between abstention, Macron, and Le Pen.

The abstention rate is likely to play an important role in the second round. Participation was already in decline in the first round in 2017. For Le Pen, who is strongest amongst social categories most likely to abstain, the key will be to get out her electorate. For Macron, strongest amongst retired people who have a high rate of participate, the challenge will be to keep his electorate mobilized. He must convince them that unlike in the past, when anyone facing a member of the Le Pen family could be expected to win, the margins are narrower in 2022.

In this context, the Presidential debate on April 20 is worth watching. In 2017, the encounter with Macron proved to be Le Pen’s undoing. She appeared tired, unprepared, and often confused in her answers, while Macron performed very well. Le Pen will have learnt from that debacle, and is widely expected to be better prepared this time around. Macron also does not have the 2017 advantage of running as the outsider candidate. Now he is a known quantity with a record to defend.

Far from ending with the second round of the Presidential contest, the French electoral cycle quickly moves to the “third round” of the legislative elections in June, determining whether the President has a majority or has to share power with a potentially hostile National Assembly.

Since the start of the 5th Republic in 1958, “co-habitation” — when the President and the parliamentary majority are not of the same party — has occurred three times. It has never occurred since the constitutional reform of 2000, shortened the presidential term from seven to five years to coincide with the parliamentary term.

The specter of a President without a majority was in view in the 2017 legislative elections. At the time, Macron barely had a political party (En Marche!, later renamed La République en Marche) with enough candidates for legislative elections. In the end, he obtained a comfortable majority, albeit on very low turnout.

Whether La République en Marche would be able to repeat that feat, or whether the Rassemblement National — who only secured eight MPs in 2017 — would be able to secure a majority is an open question. At the national level, the tripartition of the political space is quite clear; however, at the local level, the traditional parties can hope to maintain some votes. Macron, Le Pen and Mélenchon’s party are all weaker on the ground than their long-established rivals. For the time being, cohabitation looks like an unlikely scenario, but the campaign after the Presidential election will be worth following.

So “Macron or Le Pen?” — while the near-obsessive headline of the next two weeks — is not the final question. The victorious candidate will still have much work to to do if he or she is to establish a governing authority.