India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi in the Himalayan region of Ladakh after recent Indian-Chinese clashes, July 3, 2020

Originally written for the King Faisal Center for Research and Islamic Studies:

As South Asia struggles with the political and economic effects of the Coronavirus pandemic, trouble has been brewing in the heights of the Himalayas.

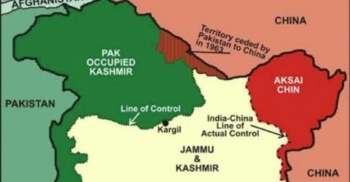

In May, reports began trickling in of scuffles and fistfights between Indian and Chinese troops at several locations along the “line of actual control”, the de- acto border between India and China in the Ladakh region. These clashes escalated into a major security incident as Chinese troops infiltrated across the LAC at six points and started fortifying positions at the eastern end of Ladakh

Indian Defense Minister Rajnath Singh tried to downplay the crisis, only alluding to the presence of Chinese troops in significant numbers and not mentioning their incursion. The first round of engagement between the two sides’ military commanders ended with a resolve to de-escalate and disengage.

But on June 15, troops clashed when an Indian patrol attempted to dislodge a Chinese camp allegedly within Indian territory. Twenty Indian soldiers and an undisclosed number of Chinese troops were killed.

India on the Defensive

The reaction of the Indian and Chinese Governments tipped off the political state of play. Indian Prime Minister Narinder Modi, with limited military options, categorically denied any intrusion or capture of Indian territory — contradicting his External Affairs Ninister, who had protested to his Chinese counterpart about the movement of Beijing’s troops on the Indian side of the LAC. The Chinese foreign Ministry was more assertive, claiming that the entire Galwan valley was situated on the Chinese side of the LAC and that the clash happened after a violation by Indian troops.

In the past month, no violence has been reported but negotiations among military commanders and diplomats are deadlocked. The Chinese troop buildup is increasing, with reports of soldiers advancing in the Depsang plains.

China is blocking traditional patrol routes of the India Army as Beijing seizes strategically-placed territory. The People’s Liberation Army can now choke Indian supply lines in eastern Ladakh. Complementary military offensives from the Pakistani-held Gilgit Baltistan region and Chinese positions in northeast Ladakh may collapse India’s position across the north of the area.

Chinese assertiveness could also embolden India’s weaker neighbors to take a tougher stance against perceived Indian attempts at hegemony. Islamabad is contesting Delhi in Kashmir, responding in kind to last year’s Indian airstrikes inside Pakistan, by dropping precision-guided munitions on an Indian Army Brigade Headquarters. India may further integrate into the US-led Quad alliance alongside Japan and Australia.

The Frontline Situation

The Ladakh LAC is a line on the ground, patrolled by both sides without any mutually-agreed demarcation on maps.

The most significant Chinese incursion is into the previously-undisputed Galwan Valley, the site of the deadly clash on June 15. This gives the PLA a vantage point to dominate the recently-built Darbuk-Shyok-Daulat Beg Oldi road, that connects the northern area with the rest of Ladakh.

With the Chinese units at a critical chokepoint, India needs to take contingency measures to ensure the stability of the northern Ladakh front against a Chinese threat in the northeast and Pakistan’s in the northwest. New infrastructure is needed, and territory cannot be left unmanned and without continuous patrolling, given the apparent scrapping of the 1993 border-management agreement by China.

This militarization will transform the LAC into a replica of the Line of Control between Pakistani and Indian administered parts of Kashmir. In Ladakh, almost five military divisions specialized in the habitat will be required alongside supplementary artillery, armored and aviation units. But this will bring financial and military burdens.

A China-India-Pakistan Triangle

The immediate motive for China’s move into Ladakh is the inclusion of India into the US’s Indo-Pacific strategy, with Delhi embracing the Quad Plus political bloc.

But there are also specific regional issues. India has been critical of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. Delhi considers any activity from the Pakistan-administered region of Gilgit Baltistan, linking the country with China, as a breach of Indian sovereignty. China has been perturbed by India’s declaration of Ladakh as a separate Union territory, distinct from Jammu and Kashmir State; its claim of the area of Aksai Chin; and its development of roads in eastern Ladakh.

The steps also bring Islamabad into a possible conflict. Indian Government officials and military commanders have warned Islamabad that they will capture the Pakistani-administered Kashmir and Gilgit Baltistan region. Pakistan can retaliate with the offensive into northern Ladakh: this would cut off the northeast of the area, including the Shyok valley and Siachen glacier, from the rest of India. The Chinese domination of the Darbuk-Shyok-Daulat Beg Oldi road would halt any Indian attempts to re-supply the northern sector.

For the first time, Pakistan has a contingency option on the ground to counter Indian moves which has the support of China, giving it strategic breathing space across the greater Kashmir region.

Meanwhile, India has failed to raise a military project of raising a China-centered mountain strike corps because of funding limitations. So instead of risking an escalation by lodging a diplomatic protest with the Chinese mission in New Delhi, the Modi Government has asked Islamabad to halve its diplomatic staff in India.

With China re-asserting itself in the Kashmiri environment, a direct Indian attack on the Pakistani side of the Kashmir valley or the Gilgit Baltistan region remains unlikely. But India could revive its tactics of the last 15 years through sabotage operations by proxies, targeting the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. The other option for India is a false flag operation against Pakistan, an act of which Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan has repeatedly warned.

No Turning Back?

The Chinese-Indian engagement within Ladakh suggests that a Rubicon has been crossed, with no chance of restoring the previous bilateral relationship. This change in the strategic and tactical picture will in turn affect Pakistan’s political and security calculus.

India may exercise strategic restraint against China, but its other neighbors, particularly Pakistan, could be targeted. Islamabad will not remain silent and will respond with a quid pro quo. This could bring an escalation to the verge of all-out war between nuclear powers.

Beyond the region, the India-US partnership will strengthen. There will be a greater domestic appetite for Delhi to play an increasingly pro-active role in America’s Indo-Pacific strategy.

Saudi Arabia will be concerned, since the Kingdom maintains cordial relations with both India and China and has a special relationship with Pakistan. Riyadh has been investing within Pakistan, notably through an oil refinery at the Gwadar port, which has been developed by China.

Could that be a way out of crisis? With the goals of peace in Pakistan and stability in South Asia, Riyadh could seek a diplomatic role to defuse regional tensions. If it does not, the situation — for energy markets, for economic activity, and for a stable balance of power — could descend out of control.