“A common thread that runs across Egypt’s policies (or, in certain aspects, non-policies) is the instrumentalization of migration — be it for purposes of soft power, bilateral cooperation, or economic or domestic political gain. The extent to which such approaches contribute to the resolution—or perpetuation—of “migration crises” is open to debate.”

Originally written for the Migration Policy Institute:

Egypt is a major migration player in the Middle East and North Africa region and in the Global South more broadly, experiencing large, diverse patterns of emigration and immigration, including significant numbers of humanitarian arrivals. As the Arab world’s most populous country, with a population estimated at 97 million, Egypt is also the largest regional provider of migrant labor to the Middle East. More than 6 million Egyptian emigrants lived in the MENA region as of 2016, primarily in Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and the United Arab Emirates. Another 3 million Egyptian citizens and their descendants reside in Europe, North America, and Australia, where they have formed vibrant diaspora communities.

Egypt has a long-standing tradition of using emigration as a soft-power tool to advance its foreign policy goals, primarily through educational initiatives across the Arab world. In the last 50 years, it has also become heavily reliant on economically driven regional labor emigration while also reaching out to its diaspora communities in the West. At the same time, Egypt has become a destination for thousands of Arab and African immigrants and a major host of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians, Sudanese, and—since 2011—Syrian refugees. Over the past few years, Egypt has also served as a transit country in migrant routes used by sub-Saharan Africans crossing the Mediterranean toward Europe.

Labor Emigration, Soft Power, and Remittances in the Arab World

i

Historically, Egypt has been a country of emigration, most of which has occurred within the broader Arab region. Its labor emigration history can be divided into two phases: first, high-skilled emigration across the Arab world throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, and second, primarily low- and medium-skilled outflows to Libya, Iraq, and the oil-producing Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries starting in the early 1970s.

Having achieved nominal independence from the Ottoman Empire much earlier than the rest of the MENA region, Egypt became a trendsetter and a major force within the Arab world. Large-scale modernization efforts throughout the 19th century, which continued under British rule from 1882 to 1952, led to a vibrant, educated elite class. Many Egyptian professionals would travel to North Africa, the Levant, and the Persian Gulf to contribute to the economic development of neighboring areas. As Arab nationalism came to dominate Cairo in the aftermath of World War I, Egyptian high-skilled emigration became a political project focused primarily on education and Arab empowerment. Under British rule, the Egyptian government welcomed the enrollment of non-Egyptian Arab students at Al-Azhar University and the newly established Cairo University, funded the construction of schools across the region, and staffed them with qualified Egyptian teachers and administrators.

This trend continued after the 1952 Free Officers movement, which abolished the British-supported Egyptian monarchy and brought to power a new generation of anticolonial revolutionary elites led by Gamal Abdel Nasser. Under President Nasser, Egypt heavily restricted labor emigration but continued to sponsor the employment of high-skilled professionals across the MENA region. In contrast to earlier efforts, such mobility constituted less a sign of Arab solidarity and more a tool of foreign policy. In the 1950s and 1960s, the government recruited, trained, and dispatched thousands of Egyptian professionals—particularly teachers—across Africa, to Latin America and, most importantly, throughout the Arab world. Once abroad, many Egyptians disseminated the Free Officers’ rhetoric on anticolonialism and anti-Zionism, and promoted nationalist sentiments—effectively serving as one of Egypt’s most potent instruments of soft power. As a result, Egyptian high-skilled emigration throughout the 1950s and 1960s played a key role in several political processes across the Global South, including the decolonization of Africa and the Middle East, the North Yemen Civil War, and the Arab-Israeli conflict.

Despite the popularity of international placements for state-sponsored professionals, the Free Officers resisted any attempt to allow broader free movement of labor into and out of its territory, as they were eager to prevent brain drain of talent or the flight of political opponents abroad. During most of Nasser’s rule, emigration was restricted and tightly regulated (although many still found ways to escape Egypt, most notably members of the Muslim Brotherhood), a policy that became untenable by the end of the 1960s. The deteriorating domestic economic situation, particularly following Egypt’s devastating defeat in the 1967 Arab-Israeli War, led Nasser’s successor, Anwar Sadat, to implement a massive liberalization of the economy in a process known as al-Infitah. As part of this shift, President Sadat recognized emigration as a citizen’s right, lifting all restrictions on Egyptians’ crossborder mobility in 1971—thereby inaugurating the second phase of Egyptian labor emigration.

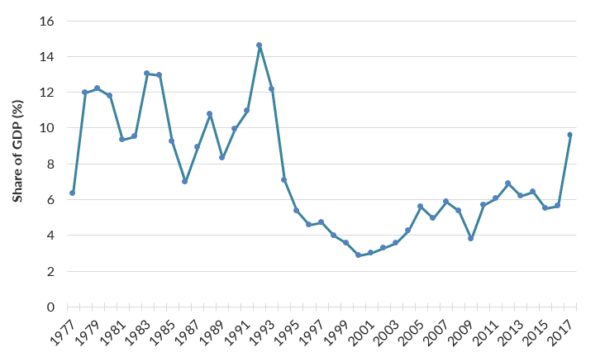

This era was dominated by large outflows into oil-producing Arab states, particularly following the 1973 oil crisis. Following the emigration policy shift, millions of high- and low-skilled Egyptian workers pursued employment across the Middle East, partly driven by domestic unemployment and the vast wage gaps between Egypt and key host countries. Since then, Egypt has considered economic remittances to be a key source of income, which now constitute a significant share of its gross domestic product (GDP) (see Figure 1). Given that money transfers are also conducted via unofficial, untraceable channels, the economic importance of migration for Egypt is even higher. Beyond remittances, labor migration has served as an important safety valve for the Egyptian government, which has traditionally struggled with issues of unemployment and overpopulation.

Neighboring Libya was the primary destination for Egyptian migrants until the mid-1970s. Once there, approximately one-third of Egyptians were employed jointly in the public administration, education, and health sectors; one-quarter worked in agriculture. From the mid-1970s onward, most Egyptian migrant workers headed to the Gulf region, notably Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Iraq. Migrant recruitment in the GCC states operates under the Kafala system, requiring hired migrants to have an in-country sponsor, who holds considerable power and control over workers. This system of migrant labor recruitment has been widely criticized by international organizations and others for enabling human-rights violations against migrant workers across the Gulf.

The post-1979 decline in oil prices has contributed to a steady fall in Egyptian recruitment in the oil-producing Arab countries. At the same time, Egyptian regional emigration to the Gulf has slowed since the 1980s due to a shift toward the recruitment of Asian migrant labor. In contrast to Arab migrants, Asian workers are considered to be cheaper and less likely to be involved in the domestic politics of destination countries.

The decision of some GCC countries to get more of their nationals into the labor force, from the early 1990s onwards, has also affected Egyptian migration flows. At the same time, the prohibition of permanent migration across the Gulf has made circular movement common, although Egyptians tend to stay in these countries for many years. This phenomenon has also increased the appeal of traditional transit migration countries — such as Jordan — which now host large populations of Egyptian migrants.