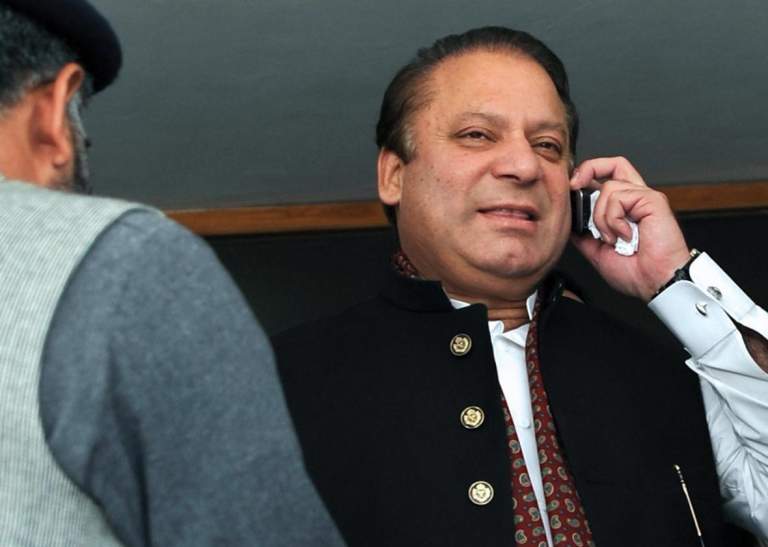

Removed from office for corruption and imprisoned, but “if ex-Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif (pictured) plays his cards right, the electoral balance may well shift toward him” in Pakistan

Editor’s Note: In July 2017, the political career of Pakistan’s three-time Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif appeared to be over. He was disqualified from office by a court over failure to disclose employment in a Dubai-based company, and he and his family faced further corruption charges.

But Sharif, who first became Prime Minister in 1990, may not be finished as Pakistanis go to the polls in search of a stable Government.

Originally published in Arab News:

As we approach the July 25 elections in Pakistan, the million dollar questions remain about who will win the polls and how the electorate will behave. In this regard, the country’s most populous province, Punjab, which also has the highest percentage of seats in the national assembly, remains the most critical variable. Any party winning more than 50 percent of the seats in Punjab has a good shot at forming the government. So, what to expect from Punjab this time?

Historically, Punjab has remained a stronghold of the Pakistan Muslim League but, in the elections of 1970, it overwhelmingly voted for the Pakistan Peoples Party. Since then, in most elections it has favored candidates hailing from the Muslim League and its various factions. In the last elections, the Pakistan Muslim League (Nawaz) dominated the province and got more than 100 national assembly seats. This was a show of remarkable political strength.

How did the PML-N win over Punjab? For that, we have to delve into the political demographics of the province. In urban areas, political parties are vying for an electorate that is relatively well educated, politically liberal and demanding of good governance, the eradication of corruption and improved provisions of basic life amenities. On the other hand, in the rural hinterlands, the politics revolve around kinship ties and having a say in matters related to the police and judicial process. A politician that has the necessary kinship ties and influence within the courts and police is what we call an “electable” in Pakistani politics and the fulcrum of rural politics. One cannot win the political jackpot of Punjab without having a good many electables. In 2013, the PML-N pulled all such candidates into its ranks irrespective of their past political affiliation or ideological differences.

It would not be wrong to say that Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf had a rude awakening in the 2013 elections and learned the hard way that its message of change might attract massive crowds to political gatherings and inspire people to vote in large numbers, but it is still not enough to win an election. PTI’s former secretary general and Imran Khan’s close aide Jahangir Tareen, himself a constituency politician, realized this and convinced Khan to adapt accordingly. The Tareen model replicated, to some extent, the strategy devised by Amit Shah, the president and main strategist for India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party. At first, it was simply getting the second best candidate within a constituency into the party fold and, when people started deserting the PML-N’s ranks, the priority shifted to sitting members of the national and provincial assemblies.

This scheme gained vital help in the form of the Panama Papers scandal that eventually led to the disqualification and removal of former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif. These events drove him to adopt hostile rhetoric against the country’s powerful military and judiciary, while his younger brother and former Chief Minister of Punjab Shehbaz Sharif trod a more conciliatory path. This situation further tilted in PTI’s favor as, with the end of the PML-N’s government, the defections from its ranks gathered pace. Tareen’s model was in full swing thanks to his own efforts and also due to the wider political conditions.

With the political fortunes of the PML-N hanging in the balance, heavy monsoon downpours brought no relief and submerged most of Punjab’s cities. The most dramatic scenes were witnessed in the PML-N’s stronghold and the provincial capital of Lahore. The hometown of the Sharifs and model of their development work was waterlogged. The endemic sewerage problems apparently were never fully addressed and the city, which claimed to have been converted into a Pakistani Paris, instead projected a picture of Venice. As if the rains were not enough, the remaining political prestige of the former ruling party got a further jolt from the conviction of Nawaz Sharif and his political successor and daughter, Maryam Nawaz.

The Perception of Reality

How will Punjab behave this time? Sharif’s party is undoubtedly in meltdown in South Punjab after the mass defection of its members to PTI and, with the possible exception of Bahawalpur District, it remains politically irrelevant. In the north and west of Punjab, it has also found it hard to maintain its political ground. Only within the districts of central and eastern Punjab has it been able to field strong candidates while still battling a resurgent PTI.

For now, the PML-N’s fortunes in Punjab are hanging in the balance and they can only take a turn for the better if it can turn around its voters’ perception of the political reality. The disqualification of Nawaz Sharif and his conviction have formed a general perception amongst voters that his electoral politics are in a severe crisis. It is not reality, but it is the perception of reality that matters in Pakistani politics. With Nawaz returning to Pakistan and emphatically propagating his rhetoric of being victimized by the country’s powerful institutions, there is still a possibility he can galvanize and rally his voter base into believing that his party is still a winning horse.

His homecoming will have a significant impact on the electoral winds in Punjab and, if he plays his cards right, the electoral balance may well shift toward him.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks