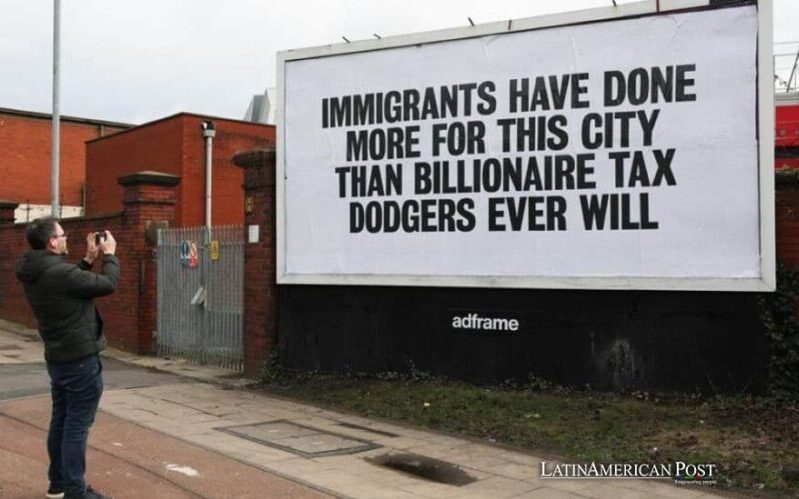

A billboard outside Manchester United’s Old Trafford Stadium responds to part-owner Jim Ratcliffe, February 13, 2026 (Adam Vaughan/EPA/EFE)

Jim Ratcliffe, a tax exile residing in Monaco who is reportedly the UK’s second-richest man, decided to become a political commentator last week.

In an interview with Sky News, Ratcliffe, the founder of the INEOS chemicals group, launched a rant filled with misinformation and invective:

You can’t have an economy with 9 million people on benefits and huge levels of immigrants coming in….

The UK has been colonized by immigrants, really, hasn’t it? I mean, the population of the UK was 58 million in 2020, now it’s 70 million. That’s 12m people.

The billionaire was wrong on his basic facts. The Office of National Statistics estimated the population of the UK was 67 million in mid-2020 and 70 million in mid-2024. The UK population was around 58 million in 1995 — 25 years before Ratcliffe’s claim of 2020.

More importantly, Ratcliffe’s declaration that the UK is being “colonised” by migrants is not just inflammatory. It’s historically illiterate if politically calculated.

The tax exile is part owner of Manchester United Football Club, which I passionately follow. Its identity is inseparable from migration, a global movement, and working‑class internationalism. But Ratcliffe warns the UK is under threat from the very forces that have helped build the sporting brand he owns.

Ratcliffe should have read the history of Sir Matt Busby, the manager who built Manchester United. Born to an Irish immigrant family in Scotland, he gave his life to the club. He survived the 1958 Munich Air Disaster, with seven players whom he loved as sons among the dead. He rebuilt the club from the ashes to become one of the greatest in the world.

United’s story is inseparable from migration. It was founded by railway workers who had Irish and Scottish roots as Newton Heath in 1878, before becoming Manchester United in 1902. In a city built by newcomers, it has been led across the decades by international figures from Belfast’s George Best to France’s Eric Cantona, Brazil’s Casemiro, and today’s Ivorian star Amad Diallo. Its worldwide fan base grew through Caribbean, South Asian, and global diasporas.

Ratcliffe’s wealth is tied to a club whose very DNA is migration, movement and openness. His language of “invasion” sits uneasily with its history. Yet look who rushes to defend the tycoon: wealthy white men like businessman Simon Jordan, their politician cheerleader Nigel Farage, and a politico‑media ecosystem that has spent years stoking division while quietly securing tax breaks, public subsidies, and state‑supported vanity projects.

How The Wealthiest Manufacture Cultural Conflict

These are the same voices who told England icon and commentator Gary Lineker to “stick to football” when he expressed empathy for refugees, yet never tell Ratcliffe to stick to petrochemicals.

That is not an oversight. It is part of a long‑running strategy in which the billionaire class manufactures cultural conflict to distract from the economic decisions which benefit them. As Peter Geoghegan notes in his book Democracy for Sale, “Wealthy interests invest heavily in narratives that keep public anger horizontal rather than vertical.”

In other words, turn people against others who have the same problems as them — not against those who inflict those problems. Ratcliffe’s “colonization” rhetoric is a tactic to turn fear into political capital. Nafees Ahmed sumamrized in his Alt Reich: “Resentment is a resource — mined, refined, and weaponized by those who already hold power.”

When billionaires fear scrutiny, they reach for scapegoats. They seize anxieties about stagnant wages, housing, and public services, redirecting them away from the political and economic structures which they exploit. They lobby for deregulation, privatization, and tax cuts. Then they claim the consequences of those policies are caused by migrants, rather than by the Brexit shambles that they supported.

Moving Beyond Echo Chambers

If we want to challenge this narrative, we must first confront our echo chambers. Civil society groups, the charity sector, progressive voices, and minority and faith groups often find themselves speaking to each other in conferences, WhatsApp groups, community halls, and religious spaces.

These spaces matter. They provide solidarity, identity, and moral grounding. But they cannot be the only spaces we inhabit.

We need to stop speaking about the white working class with contempt. Too often, their concerns are dismissed as ignorance rather than understood as the product of decades of economic abandonment. When we speak with contempt, it is weaponized by the people who created insecurity in the first place.

We cannot build alliances if we only engage in internal dialogue. We cannot shift public opinion if we avoid the uncomfortable conversations happening outside our circles. Engagement must move beyond the familiar.

It is in trade unions, local campaigns, tenants’ groups, school boards and civic spaces that alliances are built and not assumed. This is where trust is formed, where myths can be challenged, and where shared interests become visible.

The billionaire class thrives when communities retreat inward. They fear cross‑community solidarity more than anything else — because solidarity is the one force that has historically defeated their attempts to divide and rule.

Facts Not Fear On Migration

We also need honest conversations about migration, rather than the fear‑based narratives pushed by billionaires or the defensive silence that sometimes occupies progressive spaces. Migration brings opportunities as it benefits societies, the economy, and the tax ecosystem. But it also brings pressures: so we need investment in housing, services, and infrastructure. These are legitimate concerns which must be addressed with facts not caricatures.

We need a politics that can hold two truths at once: migrants are not the cause of Britain’s insecurity, and communities deserve support to manage change.

Research by the University of Birmingham’s Stephen Jones cuts through the convenient myth that hostility towards Muslims or the Gypsy, Roma, and Traveller communities is a “working‑class problem”. His findings point to the opposite conclusion: the higher the class, the more entrenched the anti‑Muslim and anti‑Gypsy sentiment. Prejudice is strongest not in the communities living side‑by‑side with minorities, but among those with the most distance, the most insulation, and the most power.

Yet we are constantly told bigotry is a pathology of the white working class, a narrative that conveniently obscures the role of elites in shaping, funding, and amplifying hostilities. It is easier for the billionaire class to blame the poor than to confront the prejudices of their own social circles, and easier still to weaponize those prejudices to divide the very communities who might otherwise unite against them.

This is why Ratcliffe’s rhetoric lands. Not because people are inherently hostile, but because they are living through insecurity created by the very class he represents.

The History of Solidarity They Want Us to Forget

The idea that working‑class communities and migrants are natural enemies is a myth. British history tells a different story. At Cable Street in 1936, Jewish, Irish, socialist, and working‑class communities united to stop Oswald Mosley’s fascists. In the 1970s, the National Front was confronted not by the wealthy but by working‑class anti‑racist movements, trade unions, and migrant communities standing together. The Grunwick strike from 1976 to 1978, led by Asian women, became a defining moment of cross‑community solidarity, as miners, engineers, and postal workers joined the picket lines.

At its core, this is a class issue. The billionaires wants the topic to be “race” because racism divides more easily than class. The tactic obscures the structural causes of inequality and pushes people to fight horizontally rather than vertically.

Ratcliffe’s “colonization” rhetoric is not about protecting Britain. It is about protecting his interests. It is about providing ammunition for the hard right — the Reform Party, its leader Nigel Farage, and its national outlet “GB News” — to spread the misinformation on behalf of the billionaires.

We cannot defeat this narrative from within our own bubbles. Working‑class communities must be engaged with respect, not contempt. Migrants must be seen as partners and not pawns in someone else’s culture war.

The billionaire class prefer our isolation, our fear, our anger. They do not want us talking to each other and mobilizing. For we stand together, as at Cable Street or Grunwick, we become a force for justice.

Solidarity is the oldest weapon we have. It is the one that they pray we never wield again.

Last Thursday, Manchester United — rebuilt by a Scottish-Irish manager, elevated by players from every corner of the globe, and sustained by a worldwide working-class fanbase — issued a statement.

The club made no direct reference to Jim Ratcliffe’s comments from a day earlier. Instead, it went higher.

Manchester United prides itself on being an inclusive and welcoming club.

Our diverse group of players, staff and global community of supporters, reflect the history and heritage of Manchester; a city that anyone can call home…..

We have embedded equality, diversity and inclusion into everything we do.

Solidarity.