Ryan O’Farrell writes for Tahrir Souri:

See also 1st-Hand: A Barrel-Bombing in Aleppo

The Syrian regime’s barrel bombs are now a daily feature of the civil war. Crude improvised explosive devices, they initially were oil drums filled with TNT, gasoline, and shrapnel, detonated by a cigarette-lit detonation cord. They are indiscriminate, inaccurate weapons pushed out the back of transport helicopters, often detonating long before or after they hit their targets because of improper timing on the burning safety fuse. These seemed to be weapons of a desperate military, one unable to supply its air force with modern weapons for air strikes, and one resorting to transport helicopters for lack of ground-attack platforms.

As the use of barrel bombs has expanded, making up for the regime’s lack of more sophisticated aerial weapons, their design has become standardized and they have taken on a strategic value in the regime’s urban warfare strategy.

Even when backed by airpower, armor, and foreign fighters from groups like Hezbollah, the Syrian military has a limited capacity for seizing urban territory. Rebels had been able to turn built-up areas like Old Homs, Darraya, Jobar, and eastern Aleppo city into fortresses of the mazes of wrecked apartments, narrow alleyways, and supply tunnels.

The regime began adopting different tactics, particularly in the suburbs of Damascus, in spring 2013. Rather than attempting costly and largely ineffective assaults on fortified urban areas to seize them, the Syrian Arab Army began encircling them, cutting off food and medical supplies.

“Starvation or surrender” has been a brutally effective weapon. Several neighborhoods and suburbs of Damascus, such as Moadamiyah, Qaboun, Barzeh, and Al-Qaddam have reached ceasefire agreements with the government, usually in return for food and some level of autonomy where the former rebel fighters remain in control.

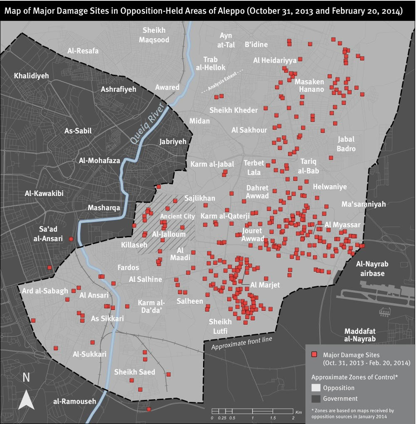

Barrel bombs can play their part in the strategy, for example in Aleppo city, where they have killed almost 3200 civilians since December.

The strikes are not a direct assault on insurgents, who have lost only 47 men to the attacks. Fighters are in the front lines in the city, which are rarely –– if ever –– targeted because the lack of accuracy means barrel bombs could hit regime forces. Instead, many barrel bombs have targeted markets or bus stations, and “double-tap” strikes have dropped two bombs 10-15 minutes apart, causing casualties amongst first responders.

So what is the strategic purpose of the airstrikes, if they do not kill insurgents?

It lies in what is effectively a mass expulsion of civilians, as hundreds of thousands have fled the affected areas. As regime forces have advanced northwards, moving from the airport to Sheikh Najjar industrial city and relieved besieged troops in Aleppo Central Prison, the barrel bombs have emptied much of insurgent-held eastern Aleppo. In one neighborhood, Karm Al-Maysar, 95% of the population has fled to the countryside.

According to activist Imad Syrian, more than 22,000 families were displaced from the Sha’ar neighborhood, and more than 200,000 people fled Masakin Hanano. Abu Al-Majd, a field activists in the Maysar neighborhood, estimated 60,000 residents went to the countryside.

Patterns of attacks on specific neighborhoods may indicate the government’s future plans for retaking the city. Massive concentrations of bombs in Myassar, near the western edge of the government-controlled airport, and Sheik Lufti and Al Marjet, close to fighting in Aziza village, show attacks between government-controlled areas in the eastern countryside to government positions in the western half of the city….

By expelling hundreds of thousands from their homes under the threat of death, injury, and destruction of property, the government has set the stage for its troops to surround and besiege rebel-held Aleppo. Barrel bombs have served as an extremely effective, albeit horrifically cruel, means of clearing the path.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks