“The policy-making process has been dysfunctional to the point of non-existent in this White House”

Maria Ryan of the University of Nottingham, and the forthcoming The Trump Project, writes for The Globe Post:

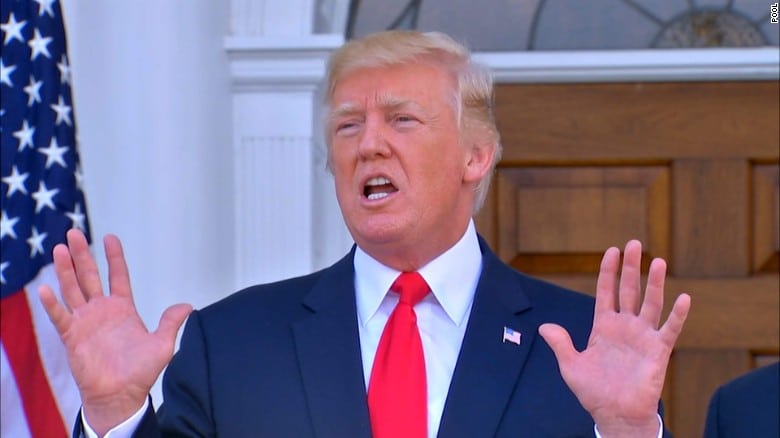

The news this week from the US intelligence community that North Korea has successfully produced a miniaturized nuclear warhead that can fit inside its missiles was greeted with a belligerent outburst from President Donald J. Trump that not even his closest aides expected: “They will be met with fire and fury like the world has never seen.”

The spontaneous threat apparently took even members of the cabinet by surprise. Asked the following day whether he had been too tough, Trump responded, “Frankly…maybe it wasn’t tough enough.”

Trump’s words may have been shocking, but seven months into his presidency it is not surprising that he should weigh in with such antagonistic and indiscreet comments – his stock-in-trade – nor that his advisors were bewildered by it. The policy-making process has been dysfunctional to the point of non-existent in this White House, replaced by Trump’s impetuous tweeting – to his base, to the Republican Party, to the rest of the world.

Almost immediately, Trump’s North Korean threat was moderated by Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and Secretary of Defense James Mattis. Americans could “sleep well at night”, Tillerson stated. Trump was “just reaffirming that the United States has the capability to fully defend itself from any attack”.

Mattis, a retired four-star General, offered forceful comments on Washington’s ability to defend itself but also declared that “our State Department is making every effort to resolve this global threat through diplomatic means”, thus leaving the door open for a peaceful resolution.

Speaking on Fox News, however, White House advisor Sebastian Gorka underlined Trump’s hard line stance with equally aggressive comments: “He’s saying don’t test America, and don’t test Donald J. Trump….We are now a hyperpower. Nobody in the world, especially not North Korea, come close to challenging our capabilities.” In response, North Korea threatened to target a former American colony, now the non-incorporated U.S. territory of Guam in the Pacific Ocean, where Washington has a military base – an attack which, if it actually came to pass, would surely mean war.

Who Speaks for the US?

Trump’s latest outburst, and the response of his advisors, provokes an important question: who speaks for the United States on matters of national security (or anything else for that matter)? There is no message discipline in the Trump Administration. The President has been consistently and recklessly belligerent on foreign policy, while Mattis and Tillerson have usually tried to dampen down tensions and revert to the status quo ante. (In the North Korean case, this was hardly anything to cheer but at least it avoided the nuclear war bluff.) Which of the three men represents US government policy? Who should foreign governments listen to?

Eastern European countries that value the collective security guarantee of the NATO alliance (Article 5), in the face of Russian aggression in the former Soviet space, have faced the same dilemma: Trump has been somewhat hesitant about affirming his commitment to Article 5, while Mattis, Tillerson, and Vice President Mike Pence have all offered the traditional robust endorsement of it. Who speaks for America? And how do other governments respond to the United States if they are unsure of its policies?

Trump’s twittering adds to the confusion. Are his tweets explanations of official US government policy that should be taken seriously in capitals around the world? Or are they just late night/early morning rants to let off steam? Should the words of the U.S. President be politely ignored these days? This is even more important when it comes to nuclear diplomacy. As it stands, the substance of U.S. policy towards North Korea is unclear. Is Trump willing to pursue talks, and if so in what form? Is he still seeking to enlist China’s help? Or is a preventive strike, possibly nuclear, his first option (if not necessarily the first option of others in the cabinet)?

Trump himself lacks the knowledge, patience, and diplomatic skill to forge a coherent policy from the White House, while Mattis and Tillerson lack the authority to speak for the whole government — and may well also lack the skills: Tillerson, like Trump, has no governmental experience and has been a relatively aloof Secretary of State so far, while Mattis spent his entire career in the military.

This message confusion makes the risk of accidental confrontation greater. Most of us probably assume (or hope) that both sides know that nuclear war is in no one’s interest. But never underestimate the importance of credibility in international relations. Most leaders avoid issuing threats they cannot, or will not, later act on if necessary; to do so risks losing credibility in the eyes of the international community.

Trump is a man obsessed with his own image: this week he launched his own TV channel, ‘Trump TV,’ to counter what he calls the ‘fake news’ and portray himself in the flattering light that he craves.

When it comes to war and peace, the danger is that Trump’s escalating rhetoric may be hard to back down from. As long as other prominent members of the administration continue to hold out the prospect of talks, Trump can reverse course with a modicum of dignity. Given his impulsive temperament, his ignorance of the policy-making process, and his lack of historical awareness, it seems unlikely that Trump’s sabre-rattling will stop anytime soon.

In the meantime, we should hope that North Korea doesn’t take the words of the US President as literally or seriously as it has in the past. Realistically, the risk of nuclear war seems slight, but it is real.