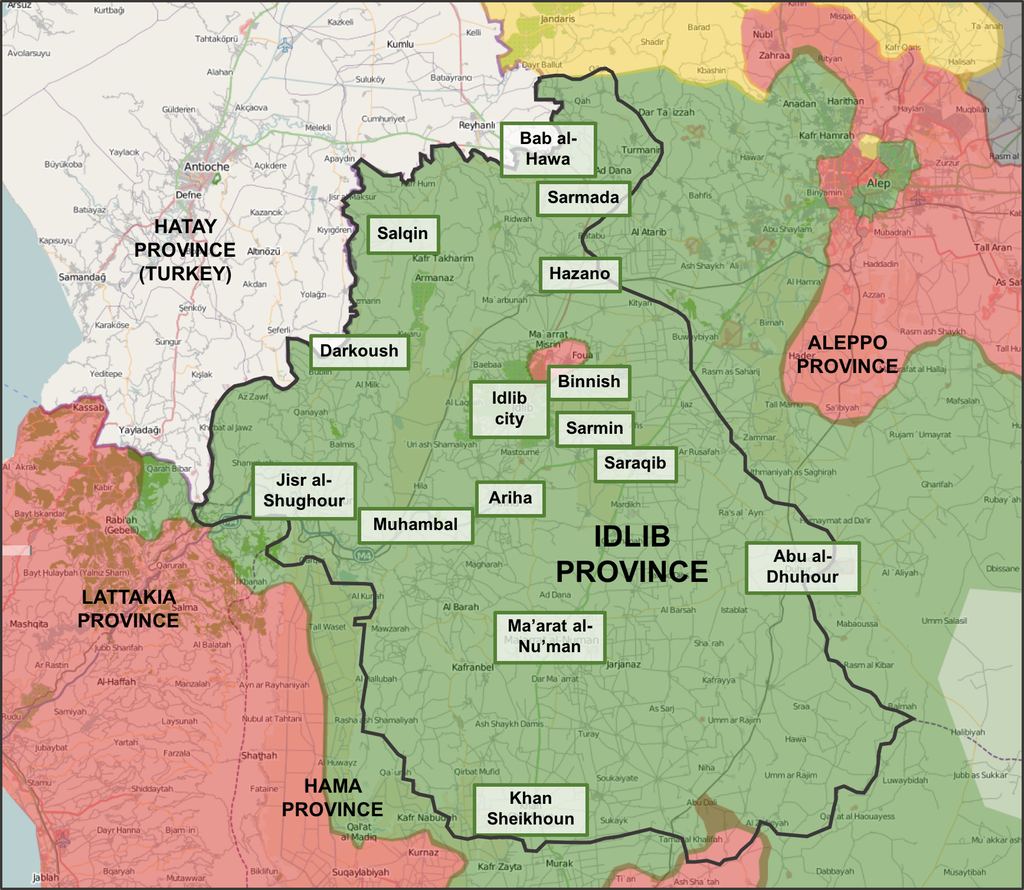

PHOTO: A council meeting in Saraqeb in Idlib Province

Sam Heller writes for The Century Foundation about the challenges to provide public services in opposition territory in northwest Syria:

As the regime of Bashar al-Assad recaptured strategic sections of insurgent-controlled Syria in 2016, Syria’s rebel-held Idlib province increasingly became the heart of the uprising in the north of the country, the dynamic center of the armed opposition. As the sole province almost entirely under rebel control, Idlib emerged as a key proving ground for Syria’s rebels as they sought to demonstrate how they would govern Syria’s “liberated” areas.

The Assad regime has staked its claim to legitimacy in large part on the continuity of its state institutions, including normal municipal services. Opposition governance and service provision in Idlib and elsewhere have thus posed a direct challenge to regime authority. Yet governance and public services in Idlib have also become another space for intra-opposition competition. Nascent civilian bodies have contended for resources and public support, but they have also been joined by major rebel factions and service institutions linked to armed groups.

The Syrian opposition has remained broadly united by its resistance to the Assad regime. But an examination of opposition governance in Idlib shows how civilian and military elements of the opposition, in parallel with their ongoing war against the regime, have engaged in a lower-key struggle behind the lines to secure influence and define the political order for which they’re fighting.

The dislocating effects of Syria’s war and a mechanism for international assistance that coordinates directly with local authorities have together produced a fragmented Idlib, administered by more than a hundred city- and town-level bodies, known as local or municipal councils. These miniature governments have provided the basic services that have maintained some minimum quality of life in Idlib’s opposition communities, including utilities repairs, sanitation, sales of subsidized bread, and relief distribution. They have also served as an experiment in participatory government after decades of authoritarian control and, in theory, a center of popular legitimacy independent of both the Assad regime and armed factions.

Map: Agathocle de Syracuse

Local Councils and Armed Factions

The uneven performance of the local and municipal councils, their inconsistent foreign backing, and the lack of any supra-local organizing framework have provided an opening for service bodies linked to armed groups. Idlib’s two main Islamist or jihadist factions, the Fateh al-Sham Front and Ahrar al-Sham, have backed service bodies that compete with each other as well as with civilian bodies supported by foreign donors, like the Idlib Provincial Council.

In the city of Idlib (the capital of the province), Ahrar al-Sham and Fateh al-Sham have also jointly established an alternative to the purely civilian local council model, a civilian service administration under a council of armed factions.

According to local observers in Idlib Province, these bodies with links to armed groups have aimed at either rationalizing Idlib’s governance and services sector or magnifying their respective factional backers’ influence on the ground. But none have been perfectly successful, in part because of the impossibility of restoring normal civic life under periodic, indiscriminate aerial bombing, and these bodies’ own limited resources and capacity.

The local councils, as the main vector for international support, have been made the focus of an assortment of Syrian parties interested in steering external assistance. Constituencies such as powerful local families have attempted to coopt or replace local councils and thus shape civic life in their communities, as have armed groups, both through linked service bodies and as individual hometown rebels.

“If you’re not a guy with a gun or backed up by someone with a gun, then your connection to power is through assistance,” said one Western development worker, interviewed on condition of anonymity because he is not authorized to speak publicly.

Overlapping Relationships of Influence

But it is often international relief organizations, charities, and development contractors based outside Syria’s borders that wield ultimate control over assistance inside the country, and which armed groups and other actors have learned to operate with and around. The result is a rebel territory that is simultaneously atomized and bound up in overlapping, tangled relationships of influence and control between local service bodies, influential clans, armed groups, and international organizations.

Rebel-held Idlib is a showcase for how rebels can pursue influence in nonmilitary spaces, as they reverse-engineer international aid dynamics and, through relatively sophisticated administrative structures, compete with each other for legitimacy. It also demonstrates how, in a civil conflict, even seemingly mundane municipal services like trash disposal and road repairs can be inseparable from issues of political and military control. The civilian and military opposition in Idlib had hoped to create a revolutionary alternative to the Syrian state under the Assad regime. In important ways, they have fallen short. But the service bodies and administrations they have built have shown how insurgents can challenge an incumbent regime’s claims to state legitimacy; how they can construct functioning, participatory government, even amid an ongoing civil war; and how they can invest those efforts to win local legitimacy.

This report is based on more than two dozen interviews conducted in person in Turkey and over WhatsApp with Syrians inside Idlib in May, July, August, September, and October 2016, as well as a review of relevant Syrian press and social media. Interviewees included Western development workers and Syrian activists, rebels, humanitarian workers, and officials involved in local governance and service provision. Restrictive border measures taken by the Turkish government and the security situation inside Idlib mean that access to Idlib is limited. Dangers include aerial bombing, but also the threat of kidnapping by entrepreneurial criminals and some of the groups referenced in this report. With some exceptions, independent Western researchers and journalists can no longer safely work inside Idlib province. This report instead relies on interviews conducted remotely, including with local council officials contacted through their councils’ Facebook pages, or through in-person meetings in neighboring Turkey. This report aims to be transparent about its sources and methods, and its assertions should be considered in light of the limitations on qualitative research inside Idlib and the rest of northern Syria.