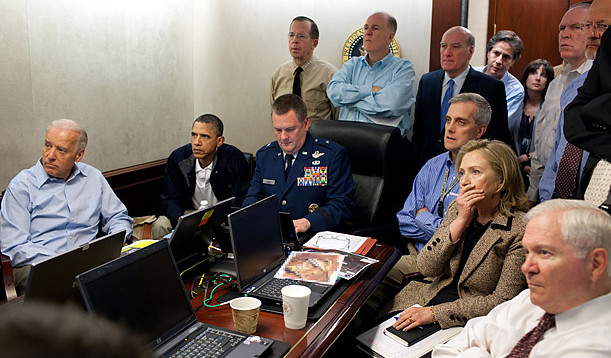

PHOTO: President Obama and senior advisors watch the killing of Osama bin Laden

Published in partnership with The Conversation:

In May 2011, President Barack Obama announced that US special forces had killed Osama bin Laden, the Al Qa’eda leader who oversaw the attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon on September 11, 2001:

The death of bin Laden marks the most significant achievement to date in our nation’s effort to defeat Al Qa’eda.

Yet his death does not mark the end of our effort. There’s no doubt that Al Qa’eda will continue to pursue attacks against us. We must –- and we will — remain vigilant at home and abroad.

Five years later, the US — and the rest of us — face a world with far more violence and destruction than that caused by bin Laden. Thousands died on 9/11, but hundreds of thousands more have perished in conflicts, from the Middle East of Syria, Iraq, and Yemen to the Africa of Nigeria, Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Millions have been displaced, many with no prospect of resettlement.

But Obama was wrong. In the spiral of death and instability — the end of the “liberal international order” declared by American analysts — Al Qa’eda is not the chief culprit.

Instead, bin Laden was already a bystander in May 2011, relegated years earlier to the margins of a Pakistani safe house. And since then, his vaunted organization has been overtaken by others with far more significance in their plans and operations.

The truth is that Al Qa’eda was long ago a symbol. A convenient symbol, to be sure, for many of the world’s leaders to cloak themselves in a “War on Terror”. But also a dangerously distracting symbol — for “Al Qa’eda” has become more and more a pretext to evade, and even give way to, the threats of 2016.

See also Syria Podcast: The “Rebooted” Jabhat al-Nusra, Al Qa’eda, and the Syrian Rebellion

Living on a Past Reputation

Truth be told, Al Qa’eda — as least, in the “far war” vision of Bin Laden — was largely a spent force by the end of 2005. Most of the planners and executors of 9/11 were dead or in the perpetual limbo of the US prison at Guantanamo Bay. Its international networks of finance and logistics had been disrupted, if not broken. Its leaders like Bin Laden and deputy Ayman al-Zawahiri were in their sanctuary in Pakistan, occasionally getting out an audio message — the capacity for videos was long gone — to claim relevance.

The showpieces of carnage which may have been inspired by bin Laden — the Bali bombings of 2002, Madrid in 2003, London in 2005 — were finished. Whether because of more effective law enforcement, the fatigue of the organisation, or the decimation of effective personnel, there would be no more spectacles of mass killing.

Instead, the world had moved on — thanks in part to the George W. Bush Administration, for whom Al Qa’eda was a pretext for other objectives — to new deadly spectacles. The invasion of Iraq in 2003 had devolved into a fractured country of insurgency, civil war, and sectarianism. Afghanistan, the supposed scene of “liberation” from the Taliban after 9/11, instead became an arena of competing factions — included the far-from-vanquished Taliban — with a nominal capital in Kabul.

New Movements, Old Regimes

The cottage industry of terrorism analysts and “jihadologists” spawned by 9/11 would continue to maintain Al Qa’eda was still the central challenge because it oversaw its “franchises” from Iraq to the Arabian Peninsula to North Africa. And, since the spectre of Al Qa’eda always guaranteed attention, this perception held sway in almost all of the world’s media.

But it was an illusion. If local movements had been inspired by Al Qa’eda, they had now overtaken it.

Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, a petty criminal from Jordan who met Bin Laden in Afghanistan, was finally able to create his movement amid the turmoil in Iraq in 2003. While the brand was “Al Qa’eda in Iraq”, the approach was different from Bin Laden’s, concentrating on the “near war” rather than the “far war” and using more violent methods than those considered acceptable by the Al Qa’eda leader.

In Pakistan, while Bin Laden was in his sanctuary, the US battle — including its resort to “targeted killed” by drones — were not only with the Pakistani Taliban but also local factions fighting for power and influence in the northwest, especially in Waziristan. In North Africa, a Salafist group — made up mainly of Algerians, Moroccans, and Saharan groups — cloaked itself as “Al Qa’eda in the Maghreb” for its local campaigns. The base of Al-Shabaab was always in the conflict in Somalia, even if claims circulated of a gesture of allegiance to Al Qa’eda in 2012.

Al-Shabaab fighters outside Mogadishu, Somalia

At the same time, deadly conflicts were brewing which were nothing to do with Bin Laden and all to do with authoritarian regimes. In Iraq, the al-Maliki Government was pursuing increasingly harsh measures against Sunni communities, notably in Anbar Province in the west of the country. In neighboring Syria, President Assad and his military were using a variety of methods — from house-to-house raids to sweeping detentions to the leveling of entire districts with bombs — for mass killing.

And then there were the decades-old conflicts that had helped propel Bin Laden’s initial vision. While the US belatedly addressed one of his causes by removing its troops from Saudi Arabia, the Israeli-Palestinian dispute remained beyond resolution — and would continue to remain so, amid a failed initiative by the Obama Administration — after the demise of the Al Qa’eda leader.

“Junior-Varsity” Issues

All of these demanded a far more considered approach, taking account of the local causes of conflict, than the invocation of “Al Qa’eda”. But it was far easier to take refuge in the spectre than to engage with the political, social, and military difficulties.

President Obama offered a telling and increasingly damaging example of this evasion in an interview in January 2014. A few days earlier, the Islamic State — the descendant of Zarqawi’s Al Qa’eda in Iraq — had taken advantage of the al-Maliki Government’s mis-steps to control the city of Fallujah in Anbar Province.

Interviewer David Remnick suggested to Obama that “the flag of Al Qa’eda is now flying in Fallujah in Iraq, and among various rebel factions in Syria, [and] Al Qaeda has asserted a presence in parts of Africa, too”. The President turned the challenge into a lifeline: because it was “Al Qa’eda” that mattered, the threat of the Islamic State was limited. Using a basketball reference, he suggested that ISIS was only a second-tier university team, compared to Al Qa’eda’s elite professional Los Angeles Lakers:

The analogy we use around here sometimes, and I think is accurate, is if a JV [junior varsity] team puts on Lakers uniforms, that doesn’t make them Kobe Bryant [a Lakers superstar].

President Obama with David Remnick

Within months, the Islamic State had shredded Obama’s complacency. It pushed aside Al Qa’eda, breaking all ties of allegiance, and embarked on a lightning offensive which took much of Iraq, including the cities of Mosul and Tikrit. It presented the US with a problem — the control of large areas, with millions of people, under the declaration of a “caliphate” — which Al Qa’eda could never offer.

But in every evasion, there is a silver lining. Instead of confronting the local reality, Obama simply moved the label of “terrorist” from the remainder of Bin Laden’s men to those of the Islamic State. He dislocated the new threat from its local setting, even using an acronym — “ISIL” — which made no reference to either Iraq or Syria.

We continue to face a terrorist threat. We can’t erase every trace of evil from the world, and small groups of killers have the capacity to do great harm….One of those groups is ISIL.

Indeed, the bonus for Obama was that he could use “ISIL” and the Al Qa’eda spectre to remove himself from other quandaries. For example, his policy towards Syria was in disarray by 2014, as the regime not only defied calls for President Assad’s removal but added chemical weapons to its attacks on opposition areas. Obama vetoed any effective response, and he now also faced an Islamic State intent on expanding its territory — and ready to execute Western hostages if the US tried to stop that expansion.

The solution? Change the priority from a response to the Assad regime to confrontation of “ISIL”. Buttress that shift with the invocation of “extremism” to tarnish much of the rebellion within Syria. And, in so doing, replace the reality of the Syrian challenge — 100,000s killed and millions displaced — with “terrorism”.

This neatly collapsed the incredibly complex Syrian catastrophe into a simple counter-terrorism problem, and set the stage for two years of disastrously negligent US policy.

Had the spectre of al-Qaeda not dominated the US’s security policy for so long, perhaps the Obama administration would’ve been more imaginative and less blinkered. Instead, the long-standing obsession with the group has worn a deep groove that US foreign policy seems unable to escape.