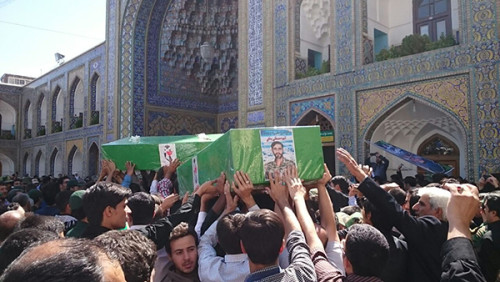

PHOTO: Funeral this week for two brothers in Iran’s Revolutionary Guards, killed fighting Islamic State near Palmyra in Syria

Thomas Pierret, one of the leading analysts of the Syrian conflict, writes for Inspired by Syria:

The recent nuclear deal has revived hopes that Iran would prove more open than before to the idea of a negotiated solution to the Syrian war.* However, a close examination of the interests Tehran is defending in Syria, and of the means it possesses to preserve them, suggests that Assad’s patron is unlikely to change course in the now four-year old conflict. As a consequence, the most probable outcome of the nuclear deal will be to provide Iran with additional financial means to militarily shore up its Syrian protégé.

For Iran, what is at stake in Syria is both huge and remarkably narrow: it is Hezbollah.

For sure, the alliance with Damascus used to mean more than that for the Islamic Republic, namely, a significant foothold in an otherwise largely hostile Arab state system. Yet, as Syria turned into a failed state beyond repair, its status in regional politics shifted from that of key player to everyone’s battlefield.

For Iran, therefore, the only value of those parts of Syria that remain controlled by Assad is that they constitute Hezbollah’s strategic depth. This strategic depth is not conceived as a mere buffer zone protecting the Shia militia’s dominant position in Lebanon from a potentially hostile post-Assad Syrian regime. Rather, its purpose is to enable Hezbollah to sustain an arms race with Israel by providing state-of-the art weaponry like ballistic and surface-to-air missiles, and resupply in case of a remake of the July 2006 war.

In other words, Iran wants a Syrian regime that is not only a neutral, harmless neighbour to Hezbollah, but a proactive strategic ally that puts its ports, airspace, airports, military roads, defence industry, and secret warehouses in service of Nasrallah’s movement.

From that angle, it is clear that for Iran, the Syrian conflict is a zero-sum game because no genuine, that is, inclusive, transition could salvage Tehran’s interests in the country. Were such a transition to happen, Iran’s strategic assets in Syria would face multiple threats from the formerly oppositionist component of the new regime, ranging from critical intelligence leaks to direct military action.

In principle, there would be three ways to avoid this, all of which are, in practice, fanciful. First, the new power structure could be designed in such a way that ex-opponents abandon the control of the entire military apparatus to former regime members. In a mukhbarat state whose civilian institutions were long hollowed out by military strongmen, then further weakened by the civil war, this would mean that former opponents would actually exert close to zero power. In other words, such a “transition” would not be a genuine one, and would consequently be rejected by any credible opponent.

Imagining that powerful popular constituencies could pressure former opponents into protecting Iran’s military assets is equally ludicrous. Despite long-standing ties with Syria’s political-military elite, Iran largely failed to acquire meaningful influence within the country’s society. Most of its investments in Syrian economy went through regime members and cronies, rather than through more grassroots networks like those that link the broader private sector to Turkey. Iranian-funded hawzat and shrines essentially catered for a non-Syrian public, and were largely perceived among religious-minded Sunnis as evidence of the regime’s pro-Shia sectarian bias.

What remains, thus, is sheer hard power in the form of direct Iranian support for the remnants of the Syrian military and its increasingly powerful auxiliary militias. Yet, the latter principally recruit among a narrow constituency of minorities that would be largely outweighed, in a post-war order, by those who see Iran as an evil empire that bankrolled Assad’s killing of hundreds of thousands, displacement of millions, and destruction of much of the country’s infrastructures.

A third possibility would be for the former opponents’ external patrons to see to it that their Syrian clients do not harm Iranian interests. This hypothesis is even more absurd than the previous ones, since none seriously believes that Iran could ever see the USA or Saudi Arabia as trustful custodians of Hezbollah’s supply lines in Syria.

Whether the opponents that take part in a Syrian transition are “moderates” or “radicals” actually matters very little to Iran: it is any move towards power-sharing that is intolerable to it, as it would be incompatible with the preservation of its core interests in Damascus. Therefore, the only way Iranian influence in Syria can be shared is in a territorial way, that is, as many recent reports indicate, by falling back on a pro-Iranian rump state along Lebanon’s border, and gradually abandoning the country’s peripheries to the opposition.

This will be a costly option for Tehran, as it implies a long-term commitment to fund Assad’s war effort and make up for his increasingly acute manpower shortage. Yet, this choice might be less unrealistic than it appears.

First, the military standing of loyalist forces remains extremely strong in Damascus and Homs. This results from the concentration of the largest and best part of pro-regime troops in these regions, but also from the fact that displacement has made local Sunni communities easier to manage for counter-insurgents: many left the country, and others have regrouped in population centres that are kept in check through siege and bombardment. Second, Tehran can count on the fact that Western powers are far more concerned with the putative consequences of Assad’s fall than with the apocalyptic cost of its survival. In particular, the Western countries’ tendency to see Assad as a bulwark against Jihadi expansion, rather than as root cause of the latter, means that they are already de facto committed to the preservation of the incumbent regime, hence to the success of the Iranian strategy.

There is no political solution in Syria without Iran, but the latter is unlikely to get on board in the foreseeable future. In practice, this leaves Western countries with two options: the first one is to alter the military balance on the ground so as to change Iran’s calculations by making its strategy unsustainable in the short term; the second one is to keep on uttering ritual calls for a negotiated solution during another decade of war.

It is possible that the author of these lines lacks imagination and creativity. It remains, however, that any serious contribution to the present debate should answer the three following questions: First, what are the interests that Iran should, or should not, be allowed to preserve in a post-Assad Syria? Second, are such interests compatible with a power-sharing arrangement that meets the minimal requirements of the moderate opposition? Third, what logical conclusions can be drawn from the answers to the first two questions?