Nicholas J. Wheeler of the University of Birmingham’s Institute for Conflict, Cooperation, and Security writes for EA:

Speaking at a press conference on 9 February with German Chancellor Angela Merkel, President Obama said that the negotiators must overcome a “huge trust deficit” to reach a nuclear deal.

When Western leaders and politicians talk about a trust deficit, they usually have in mind Iran’s perceived lack of trustworthiness. So the Joint Plan of Action, agreed in November 2013, established a level of inspection and intrusiveness on Iranian nuclear facilities by the International Atomic Energy Agency that went beyond even the IAEA’s Additional Protocol to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty.

It is easy to forget from the Western side that the Iranians also feel a trust deficit, with their own narrative on the nuclear file that tells a story of duplicity and a lack of trustworthiness. The Supreme Leader said on 7 January, “The United States arrogantly says that if Iran makes concessions in the nuclear case, they will not at one stroke lift sanctions. With this reality, how can we trust such an enemy?” It is easy to dismiss this as domestic grandstanding by the Supreme Leader, but to do so would be to neglect how far Ayatollah Khamenei continues to operate with a bad faith model of his adversary.

It was this bad faith model of US motives and intentions that led Khamenei to pull the plug on the Tehran Research Reactor deal in the Geneva Talks of late 2009. He believed that the US Government was not negotiating in good faith when it demanded the full batch of Tehran’s low-enriched uranium to be transferred out of Iran before the fuel plates for the TRR were delivered.

The same issue of fairness recurs today with Khamenei’s questioning of why sanctions cannot be lifted quickly after a deal is agreed. From a Western perspective, the international community wants to see evidence of Iran’s trustworthiness before relaxing the measures that are believed to have brought Tehran to the table, but this position only underlines how distrust on both sides paralyses the possibility of bridging the gap over the sequencing of sanctions.

TRUST IN 2015?

The key difference between the 2009 negotiations and today’s talks is that the two Foreign Ministers, John Kerry and Mohammad Javad Zarif, are conducting the negotiations. In 2009, there was a meeting between Iran’s lead negotiator Saeed Jalili and Undersecretary of State William Burns in Geneva; however, the technical talks then moved to the IAEA and Vienna and the political negotiations between Iran and the Vienna Group. There was no official bilateral track between the United States and Iran.

Kerry has the trust of Obama, and Zarif has that of President Rouhani who — along with his Foreign Secretary — has staked his authority on the success of the negotiations.

The intriguing question is how far Kerry and Zarif have built up a personal relationship, and how much this has contributed to a successful negotiating process — even if Kerry said before the Joint Plan of Action was signed in November 2013, “Nothing we do is going to be based on trust.”

Former US official Dennis Ross has identified several requirements for interpersonal trust to grow between two negotiators:

1. Always keep to your promises and deliver what is expected

2. Be prepared to be open and reveal insights into the thinking of your leaderships that will promote a successful outcome

3. Always protect confidences and never expose your counterpart

4. “Be prepared at a certain point to deliver something of value to your counterpart that he or she knows is difficult for you to produce — indeed, even something that may cost you something”

Even if Zarif and Kerry are in the process of developing a relationship of trust, is each of them in a position to deliver something of ‘value’ to their counterpart? For this to happen on either side, it will have to come from the very top.

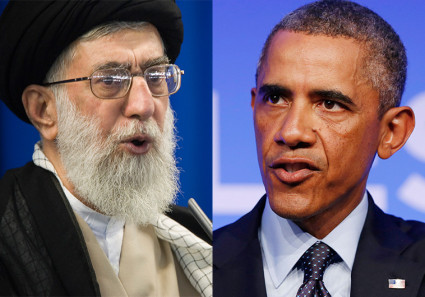

OBAMA AND THE SUPREME LEADER

Obama tried to open a personal channel of communication with Ayatollah Khamenei as early as May 2009, when there was a brief exchange of letters between the two leaders. The President’s second letter, sent shortly before the 2009 Iranian Presidential election, reportedly invited the Supreme Leader to send his personal emissaries to meet with US officials William Burns and Puneet Talwar in secret back-channel talks. The written correspondence between the leaders came to an end with the Green Revolution, when Khamenei felt Obama had meddled too much in Iran’s internal affairs, and there was no attempt by Obama to revive it when the fuel-swap talks ran into troubled waters in 2009. However, the correspondence did resume in October 2014 with a Presidential letter, and it is reported that the Supreme Leader replied earlier this year.

In the second half of the 1980s, letters between President Reagan and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev were important in building trust between them. Can the same be said for Obama and Khamenei today?

When the Supreme Leader talks of US deceit and lack of trustworthiness, it is not clear whether he is including Obama in his criticism. Perhaps he is, and he has no belief in the US leader’s sincerity on the nuclear issue. Or perhaps Khamenei does trust Obama when he says he wants a new relationship with Iran, but he does not trust the United States. To add to the complexity, the Supreme Leader might trust Obama when he says he does not want to attack Iran or weaken the Iranian political system, but he does not believe that Obama has the capacity to deliver on that commitment.

The trust deficit remains, but perhaps the material pressures on Iran are sufficiently great this time to leverage a deal. If so, it will have to be sufficiently elastic to satisfy the hawkish constituencies in Washington, while it must not appear to hardliners inside Iran as a humiliating climb-down on the sequencing of sanctions.

The breakthrough in US-Soviet relations partly came from the Soviet Union’s material weakness, but it principally came from Gorbachev and Reagan learning to trust one another. A breakthrough here, as in the 1980s, requires Obama and Khamenei to do more to convince each other that they can be trusted. In the absence of that, distrust will remain the default setting in US-Iran relations, with or without a nuclear deal.

This is an edited version of a paper presented at a seminar on “Nuclear Negotiations with Iran: Past, Present, and Future”, co-hosted by the Institute for Conflict, Cooperation and Security and Chatham House’s MENA Program on March 18.