Wednesday’s release of 16 political prisoners jailed for their role in the 2009 post-election unrest — including the prominent human rights lawyer Nasrin Sotoudeh (pictured above) — was greeted by reformists and human rights activists by equal parts of surprise and joy.

Through his rhetoric on foreign policy issues — “prudence and moderation” on Syria and “engagement” with the US over Tehran’s nuclear programme — and a relaxation of some domestic constraints, President Rouhani has tentatively begun to open up Iranian civil society. The release of these political prisoners is a move on that front.

But the decision to release the prisoners has met mixed responses from Iranian politicians and lawmakers, with some welcoming the development and others playing down its significance.

Hojatoleslam Rasoul Montajebnia, the spokesman for the reformist National Trust Party — established by opposition leader Mehdi Karroubi, under house arrest since February 2011 — intimated that the move was indicative of the change in the political atmosphere since Rouhani’s election.

Referring to the detention of Karroubi and fellow 2009 Presidential candidate Mir Hossein Mousavi, Montajebnia said, “The people hope that just as their economic issues will be resolved and concerns minimized with God’s grace, so too will prisoners be pardoned by officials and those who are under house arrest will, God willing, be removed from house arrest so that the people become more hopeful.”

Mohammad Ali Hazeri, Secretary of the University Instructors Islamic Association, also welcomed the development: “This matter strengthens and intensifies the hopeful outlook that was created with the formation of the new administration and will create a way to increase sympathy and alleviate quarrels….This release fulfills part of the expectations of society and the people of the [June Presidential] elections.”

Principlist politicians have been more circumspect, with some using the opportunity to reiterate criticism of the 2009 post-election unrest and to emphasise the need to rally around the Islamic Republic’s system.

MP Rajab Rahmani declared, “All who committed mistakes intentionally or unintentionally in any way [should] return to the arms of the Islamic Republic’s sacred system and know that there is no refuge better than the Islamic system and the velayat-e faghih [the Supreme Leader].”

He added, “We need national solidarity and unity at this stage to advance the country. We must maintain our national solidarity and everyone [should] express their statements in a free space.”

MP Hojatoleslam Mehdi Mousavinejad was more welcoming: he suggested that the prisoners’ release was “a good opportunity…to achieve the supreme goals of the revolution and the system.”

However, In stark contrast to the optimism elsewhere, Hamid Reza Taraghi, a member of the conservative Islamic Motalefeh Central Council, claimed, “This matter has no relation to the country’s current situation and political space. Rather, they were released based upon completing their sentences and according to the Judiciary system’s order.”

Taraghi warned reformists not “to pursue their previous positions and paths of conflict with the system by their presence in society.” To do so, he said, “will harm the political space that the Eleventh Administration has created and cause the emergence of new challenges”.

So a far from universal welcome of enthusiasm.

Even so, this is a significant step raising the question: was this a release for the international community — Washington in particular — or for an internal audience including the reformists and moderates who voted for Rouhani in June?

Perhaps both.

The decision fits neatly with Rouhani’s “engagement” overtures to the US, echoed by Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif’s “moderate” social media diplomacy on Syria as well as the Supreme Leader’s rhetoric of “heroic flexibility”.

At the same time, Rouhani’s supporters will see the freedom of the 16 as a move to fulfil election campaign promises, even as they expect more releases.

This is a shrewd move. As it fosters a less belligerent image of Tehran for Western observers, the Supreme Leader — probably grudgingly — accepts its benefits for Iran’s diplomatic relations with the West.

However, it also opens up some room inside Iran for discussion about a question that would have been impossible only three months ago — whether the leaders of the Green Movement, Mehdi Karroubi and Mir Hossein Mousavi, should be released from house arrest.

At the moment, the President is fortunate that the Supreme Leader’s attention is outwards, towards Syria and the thawing of tensions with the US. Rouhani has also been able to to curb the domestic political role of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps — closely aligned with the Supreme Leader — which met a tempered response by Khamenei.

So can he go farther? As EA’s Scott Lucas wrote on Thursday:

Will Rouhani dare to free the two leading symbols of the protests after the 2009 elections and the top “seditionists” for those who repressed those protests?

Will the President — can the President — release Mir Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi, the Presidential candidates who have been under strict house arrest since February 2011?

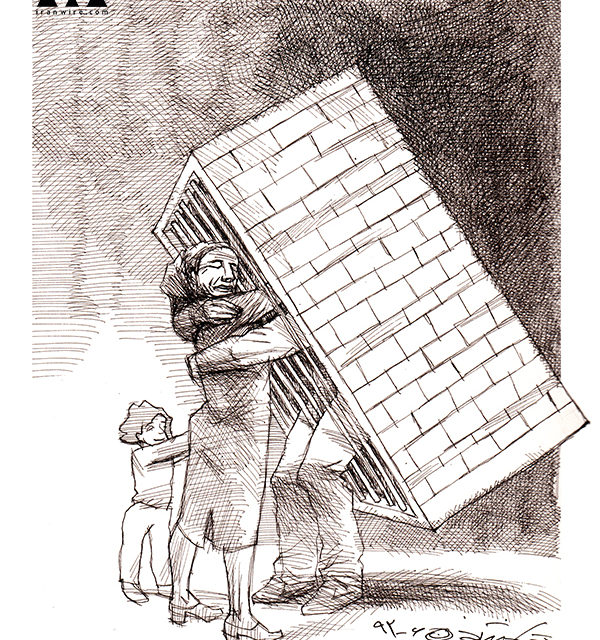

(Featured cartoon from IranWire)